You are currently browsing the monthly archive for September 2009.

Robin Hanson counters my views on human fertility

But as long as enough people are free to choose their fertility, at near enough to the real cost of fertility, with anything near the current range of genes, cultures, and other heritable influences on fertility, then in the long run we should expect to see a substantial fraction of population with an heritable inclination to double their population at least every century. So if overall economic growth doubles less than every century, as I’ve argued it simply must in the long run, income per capital must fall over the long run, a fall whose only fundamental limit is subsistence; we can’t have kids if we can’t afford them

That is, growth is not forever and selective pressure will eventually cause population growth to pick up. I agree with the growth part.

Conditional on human’s not going extinct the population part is true as well. I didn’t recognize that when Robin first mentioned it in my comments but he is correct.

That is, if we survive long enough and if we are free to choose reproduction rates then high fertility will dominate. There are a few big ifs here.

First there is the, “if we don’t go extinct.” When I was a kid one of the fist really gee whiz evolutionary stories I heard was the story of the Irish Elk (pictured above.) I don’t know if this is supported by current biological theory but so the story goes the Irish Elk was beset by opposing evolutionary forces.

On the one hand sexual selection was pushing for males with larger antlers. On the other hand larger antlers were unwieldy and required a large devotion of resources to produce. The Elk could not split the difference and went extinct.

Humans may likewise be beset with dual forces. We have these big brains, which are very useful. Mostly, I would argue, for playing the complex game of love. But, it also turns out that they can do other things, like blog, create birth control, video games etc. Bryan Caplan notwithstanding, these things are generally not conducive to reproduction.

So we have a adaptation that’s very good at satisfying our instinctual drives yet it is also good at avoiding the costs of those drives. In particular the cost of raising children. These two forces are fighting against one another, and we may not be able to split the difference.

Second, is the free to choose “if”. Robin is ultimately saying that we will reach the carrying capacity of our neighborhood of the universe. Is it likely that society will allow this to happen? Understanding the costs, isn’t it likely that some type of future one-child (or 2.1 child) policy will be implemented?

The latest from James Poulus was a bit much even for me

This is the brush that some have used to tar the Straussians and neocons. We needn’t pass judgment on the wisdom or merits of their critique in order to observe that the kind of stance attacked really has to be called conservative postmodernism and not postmodern conservatism. It’s is a postmodern position through and through, assured that all social relations are power relations and that all individual identities are masks. The conservatism is incidental — the mere ‘preference’ that motivates the use and abuse of the ‘facts’.

In response to my EMH interpretation that there is no replicable way to beat the market, Noah says

There are lots of hedge fund guys who do make a lot of money writing computer programs to time the market…

And of course computer programs are replicable — as opposed to well honed intuition, which is not replicable.

As I mentioned I have been backing off that stance.

Still, I think the question is whether or not the quants are just "picking up pennies in front of a steam roller" That is, are they making risk adjusted above average returns or have they just found a way to hide the fact that they are taking on lots of risk?

Perhaps this is something Mike Konczal would like to weigh in on.

Note obviously, taking on lots of leverage and hence risk is a key ingredient in many quant trades, but the question is whether or not you are fundamentally just making money on risk, or do you have a kernel of above average risk adjusted return.

Bruce Bartlett clips from Matt Latimer’s book and adds some of his own gems.

One of the things that Latimer talks a lot about is the importance of the president’s mood, which appears to have gyrated wildly. Apparently, the best way to get on his good side was to pretend to be stupid so that Bush would seem like a genius by figuring out some simple point for himself. Latimer says that national security adviser Stephen Hadley was very good at doing this . . .

One of the things that first turned me off from the Bush Admin was their conflation of autocracy and tyranny – as if every dictatorship was Oceania and every democracy a paradise of civil discourse. No attempt was made to distinguish (formerly) constitutional oligarchies such as Iran from totalitarian states like North Korea. This is not only bad policy but quite frankly smacks of stupidity.

As Latimer shows, it just as feasible for a democratically elected leader to repress divergent points of view – at least on the inside where they have the greatest chance of influencing policy.

Yglesias dings the efficient market hypothesis based on a conversation with German bankers

Basically they were saying we should blame the clients. “We give the customer what he asks for” they say, and (someone sarcastically) maybe “more regulation is needed on the investor side” rather than on the bankers. They say that after the crisis hit, people got very conservative but already “clients are coming back and asking for emerging market bonds and hedge funds. Banking is a customer service industry that like any customer service industry is grounded in human nature and “human nature is driven by greed and fear.”

This is plausible stuff I think. But it’s also strikingly far afield from the Efficient Markets Hypothesis . . .

I’ve been rethinking my already somewhat heterodox position on the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) recently but Yglesias is going to far.

The EMH doesn’t suggest that no traders are driven by emotion or really dumb ideas. In its strongest form it only says that being dumb won’t hurt you. Being smart won’t help you either of course, market prices always reflect the best information available.

Maybe you don’t think that’s true. I certainly don’t. But you might believe a weaker version which says that one can’t systematically do better than average. The way I have tended to view that constraint is to say, any understanding of the market or sense of timing that makes money over the long haul cannot be written down and explained. In the modern world it probably can’t even be written into a computer program.

It might, however, be tied up in the cognitive make-up of some individual. That is, maybe Buffet really can pick ‘em but that doesn’t mean you can learn to be like Buffet. His ability is wound up in his biology.

Recently, I’ve been backing away from even that. Nonetheless, none of these hypotheses rules out idiotic behavior.

I should also add that they don’t rule out mass hysteria either. There is no way to pin down what risk aversion “should be.” Suppose that everyone suddenly got more scared. They really became risk averse. Then a perfectly efficient market would necessarily fall.

Nor I would argue is there anything irrational about random fear. Despite people falling for the myth of autonomy, you are scared because of a series of autonomic reactions that may or may not be related to some true threat. Sometimes there is a threat and it can be pinpointed. Sometimes there is not a threat but people rationalize one into existence. But, at no time is your being scared dependent on there being a true threat.

Menzie Chin piles on the years long and miles deep criticism of Bush era fiscal policy

the results based on the small-scale regressions suggest that economies with larger current account deficits, rising inflation, and a deteriorating fiscal balance before a crisis experienced significantly larger output losses [from financial crises].

but he also adds the presumably still applicable

[America] needs a combination of policies to reduce the deficit substantially so that its indebtedness to the rest of the world stops rising at some point. These policies include… A concerted effort to reduce the federal budget deficit…

I applaud Chin for still pushing balanced budgets even after his political foes have lost the reigns of power.

I am becoming more convinced that silence from the center on fiscal soundness is a bad policy. Yes, the current administration should be given a chance. Yes, these are the worst of times to curtail spending or more realistically raise taxes. And, yes the loud elements of the opposition are spouting all brand of insanity.

At a minimum, however, the admin has less leverage to push deficit reducing policies when reasonable people are silent about the long run budget imbalance. General statements that “when this is all over we’ll definitely work on the deficit” are not enough.

Ideally I’d like to see long run deficit targets floated. I understand that in the middle of this fight, no one wants to talk about actually cutting entitlements. Of course no one ever wants to talk about tax hikes when political tensions are high. However, what level deficits do they see as generally achievable over a 10, 20, or 30 year horizon?

Felix Salmon and Megan McArdle lament the FDICs ability to issue treasury bonds without actually issuing treasury bonds.

If the bonds are coming from the government, that’s likely to mean they’ll be treated as government debt, and it certainly means that there’s an implicit government guarantee there. Once again, the FDIC is using government guarantees, rather than real cash, and pretending that doing so doesn’t cost the government anything. We’ve done that too many times already

Amen. But I doubt this will change. Government officials don’t care about saving money as much as the appearance of saving money. The odds are very good that by the time this government guarantee turns out to be expensive, Sheila Bair will not longer be around.

First, the government is on the hook for the FDIC’s liabilities no matter how they are structured. If the FDIC runs out of cash yet has to pay account holders then the government will step in. In the FDIC raises cash from banks but then at a latter date cannot meet its debt service, then the government will have to step in. Interjecting this step does not expose the taxpayer to more risk.

Second, this entire episode has done a lot to convince me that the basic public choice framework, exemplified by Megan’s comments is less relevant that Bryan Caplan’s rational irrationality framework.

When the poop hit the fans so to speak, it was the insulated regulators who proposed doing more, while the elected officials wanted the banks to fry. Moreover, as Nate Silver pointed out, elected officials who were retiring were more likely to vote for the bailout.

All this suggests that those who had a greater incentive to worry about their appearance really were ready to deny the banks real money. Those who had the luxury of statesmanship pushed to step in.

In the comments HappyJuggler wrties,

Sigh. Mankiw’s point is simply that not everyone is going to be able to get “comprehensive health care”. Period.

I think the simple argument that “we can’t afford to provide comprehensive health care to everyone” is basically wrong. There is some upper limit to how much health care we can produce, but we are no where near it.

Greg paints a scenario in which it would be worth it to provide comprehensive health care to everyone and says, “see we still couldn’t do it.” My point is that his example is wrong. If it were worth it, as it could be with a 150K Dorian Gray Pill, then we would provide.

The entire nature of the global economy would change. Society would be fundamentally altered but that is because you have introduced a paradigm shifting technology.

The issue we face now, however, is that we don’t want to provide comprehensive health care to everyone. My take is that we don’t want to because its not worth it. Indeed, I agree with the Hanson/Kling argument that on net we are providing too much care as it is.

Now as it happens I think that most of this excess care is in medical professionals and equipment, rather than drugs. Drugs do pretty well which is part of the reason why the Dorian Gray Pill is more intuitive than the Dorian Gray Procedure.

Nonetheless, the question issue is not, that we can’t provide health care to everyone. It is that we are providing “too much” health care to some and “not enough” health care to others.

The latter point is subject to debate, but I think its pretty clear that if people faced the true marginal cost of health care most would buy less. Yet, I also think that if the system wasn’t screwed up by the current health care insurance system, restrictive licensing and onerous drug approval then there is a fraction of the population which would buy more health care.

I must confess that I do not really get what the fuss is over Greg Mankiw’s latest NYT column.

Greg

Imagine that someone invented a pill even better than the one I take. Let’s call it the Dorian Gray pill, after the Oscar Wilde character. Every day that you take the Dorian Gray, you will not die, get sick, or even age. Absolutely guaranteed. The catch? A year’s supply costs $150,000.

. . . So here is the hard question: How should we, as a society, decide who gets the benefits of this medical breakthrough? Are we going to be health care egalitarians and try to prohibit Bill Gates from using his wealth to outlive Joe Sixpack? Or are we going to learn to live (and die) with vast differences in health outcomes? Is there a middle way?

As Free Exchange says,

His overarching point is actually not that complicated: medical treatments cost money, and so figuring out who gets what is tricky.

Greg bills this as a reason health care will never be equal. What I see is a reason that health care will never be infinite.

Pills don’t just appear by magic. They are funded by research and currently profit seeking firms. If far and away the largest market for drugs was a universally covered public then drugs will be made for a universal public. Ones with an actual treatment cost of 150K a year wouldn’t be made.

Now, suppose that for some weird reason it was profitable to develop a drug whose actual treatment costs were 150K a year. And that this drug prevented all aging! What you would see is a radical transformation in society. A massive increase in work effort and an national an effort exceeding WWII mobilization to get this drug for everyone.

Consumption would collapse. Investment would rise sharply. There would probably be rationing of everything. The entire focus of the country and likely the world would be production of the Dorian Gray Pill (DGP).

I am guessing that in a relatively short time we would achieve pills for everyone in the US and then the world would turn to the trickier task of providing it for every alive. It would shape every political discussion and every international negotiation. There would be no other issue.

In short, Mankiw’s DGP example doesn’t make sense in the context of our current social and economic structure because such a thing would radically alter our social and economic structure. In a post DGP world it wouldn’t be about preventing the rich from getting access, it would be about striving to get everyone access.

Note: Jeff Ely beat me to the title but it was too good to give up.

So apparently I am the only person who doesn’t find the ACORN videos the least bit surprising and is also not terribly put off by them. I understand that its a public relations nightmare and it will probably end the group but I am also not sure what they could have done to avoid it.

There is clearly something deeply wrong with the organization. One or two bad apples could be explained away, but six, across the country, indicates that at the very least, their HR policy is very troubled. There’s no way to defend this.

How exactly was this HR policy supposed to function and where exactly were you supposed to get employees who would not have gone along with this?

ACORN pays its workers as little as possible. It famously fought to be excluded from minimum wage laws. Their operations are not in the best of neighborhoods or the best of buildings. The perks are shall we say, minimal.

There is a reason why corporate office workers get such nice digs and 40K plus salaries. Its not because of the goodness of the corporation’s heart. Its because without these enticements they couldn’t find people who could be trusted not to regularly scam the very corporation they worked for.

Regardless people are going to scam you. All organizations tend towards corruption. The idea is to hopefully keep the corruption at manageable levels. That means hiring people who either A) have a level of neuroticism that predisposes them against taking the risk of corruption or B) have a lot to loose by getting caught.

(B) can be either social or financial. But there has to be some carrot and that means relatively high wages and status. ACORN was offering neither. It was also ruling out high neuroticism folks by having offices in rougher neighborhoods.

Thus you have an employee base that is highly prone to corruption. I just don’t think there is any way around this.

Today in ubernerd blogging: Bryan Caplan doesn’t buy Robin Hanson’s assertion that growth is not forever.

I’m baffled. You don’t have to be a sci-fi guy to think that in the next century we’ll get working virtual reality. And once we have that, why couldn’t economic growth of 1% (or 10%) continue forever in simulations? In the real world, we can’t all be emperor of an infinite universe. But I don’t see why every one of us couldn’t preside over our own simulated utopias?

As for all this talk of atoms: Economics is about value, not matter. As long as people regard vivid virtual goods as acceptable substitutes for actual goods, how can the scarcity of atoms stop everyone from having everything he desires?

I don’t think this is right. In the end even mental states must be represented by states of matter. Thoughts, I believe, have a one-to-one correspondence with configurations of the brain. At some point there must be a limit to our ability to reconfigure brains in new and interesting ways.

We should also recognize that there are a finite number of molecules in our brains. (Actually, I think we can do this with neurons but even if we assume that even re-jiggering minute structures of neurons corresponds to different thoughts). Thus there is a finite number of combinations and configurations of molecules. Thus there are a finite number of thoughts and feelings. At some point we will reach the end.

Now what we are arguing here is that either humanity is reaching the carrying capacity of our region of the universe or that we have maxed out the sum of human potential. Neither of these is likely to actually happen in my opinion.

Much more likely is that human population will drift towards and finally reach extinction long, long before we hit these constraints. I see relatively near term extinction as highly likely because modern technology is mitigating the reproduction instinct. Obviously birth control plays the major role by allowing sex without reproduction.

The ability to support ourselves with capital investments made during our working lives means that the need for children to support parents in later life is falling. This reduces the need for children.

An ever increasing range of entertainment technology makes perpetual adolescence more attractive.

Put together these factors suggest that we will reach the point were global population is contracting rapidly. Suppose that sometime in the next century global population peaked at 10 Billion and then began to decline at 2% a year. In another 1000 years, humanity would be gone.

I don’t think this is a particularly dark state of affairs, however. These days we mostly focus on the transition costs associated with an aging society, but it is important to remember that the long term effect of a shrinking population is increasing wealth.

I see the last human being on earth as being extremely happy, extremely wealthy people living in a subtropical extended adolescence. They will look and feel 22 until the day that they will die. They will want for nothing material. And they will spend their last days dancing on the beach, blissfully unconcerned about the end of humanity.

Matt Yglesias argues that Hitler was massively irrational not to keep his word and not invade Poland.

Is the conservative view that, in general, when you offer foreign countries a deal that they rationally ought to accept they will, as a general matter, usually back out of the deal even though doing so will have disastrous consequences for them? That can’t be right. At the end of the day, the reason analogies to World War II strike people so vividly is that they were so unusual. You can’t base your everyday decision-making on an extreme historical outlier.

First, just because you lose a gamble doesn’t mean its wasn’t worth taking.

Second, I think the conservative point is that you can’t trust dictators to be rational. They are crazy by nature and must be defeated.

Last year, we spent $456 billion on Medicare, and it is the fastest growing major government program. How likely is it that the people protesting Obama’s Medicare cuts will stand with Republicans if they propose cutting that program even more to balance the budget? They will switch sides in an instant. The elderly will fight anyone who tries to cut their benefits even as they hypocritically demand fiscal responsibility and rant about the national debt. The elderly are the reason why we have a national debt.

I part ways with Scott Sumner largely on the source of the 2008 surge in money demand. Scott seems to think of it as somewhat unidentifiable while I see it as a natural consequence of the subprime implosion.

In January 2008 I wrote.

A while back I suggested that smart homeowners were loading up their HELOCs before the door was shut. Turns out the door is being shut on Monday. Calculted Risk reports that both Chase and Countrywide are placing new limits on how much consumers can borrow.

Without access to Mortgage Equity can the consumer continue. Moreover, consider the on going possibility that high US consumption is being driven by a minority of consumers who have been drawing on heavily on home equity. With the door shut on those high spending consumers we could see a dramatic realignment in the US savings rate and with that a global recession.

Indeed, in the weeks after that I had a conversation with a real estate broker friend of mine on this issue. We calculated that the carrying cost of cash taken out of a HELOC was likely to be around 1% and maybe less if you found the right Certificate of Deposit. We concluded that we would not only max out our home equity lines (I had a different bank) and stuff the proceeds in savings but he would look for anyone who hadn’t shut the door yet and get us more out.

I posted Cochrane’s response to Krugman last week and in the interim this site has become the link to source. I tried to be as neutral in the posting as possible, but some may have interpreted as implicit support for Cochrane’s position. This is not the case. Indeed, at the time I wasn’t sure how I felt about either piece. Here are my thoughts as of now.

Tone

Krugman’s piece was, well, Krugman. A little abrasive and not particularly charitable to his adversaries, but smart and well reasoned nonetheless. Cochrane’s response, seemed to me, a bit out of scale to what Krugman wrote in the NYT Magazine. Now, if you’ve been following Krugman you know he has said much worse about those associated with Freshwater Macro.

Undoubtedly, this history of antagonization influenced Cochrane’s tone. Still, it felt like an escalation and that is unfortunate. I realize that this could be read as “rewarding” Krugman for being consistently rough around the edges. Its like Krugman’s caricatures don’t count because he’s always painting the other side in a bad light.

From the point of view of encouraging a civil discourse, however, I think that’s the correct approach. There are economist specific fixed effects. And, economists who are consistently abrasive already suffer an implicit discounting of their statements. Krugman often complains that he will never be forgiven for being “right too soon” about George Bush. This is probably correct and is simply another way of saying he will never escape the implicit discounting associated with his style.

Substance

Beginning with Eugene Fama’s post arguing that the stimulus could not work because it violated basic adding up constraints I have been deeply puzzled. The probability that I understand macro on a deeper level than Fama or Cochrane is low. Yet, it seems to me that basic error is being made. Fama and Cochrane appear to either be assuming that prices adjust seamlessly throughout the entire economy or that increases in the demand for money do not reduce the total quantity of transactions. Both of these seem to be naive assumptions.

However, given our premise, that it is unlikely I understand something Fama and Cochrane do not, the logical conclusion is that I am missing something about their argument. Yet, when I look at how the crisis unfolded I am struck by how well the basic model I was working with performed.

In the spring of 2008, I told my graduate seminar class that if we had not already had the Great Depression that it would be starting now. Luckily I noted, we had learned many of the lessons and Ben Bernanke would not allow a general failure of the financial system if it could be avoided.

In the days after Lehman’s fail, just over one year ago, I wrote a letter to my colleagues in the School of Government telling them we were walking a fine line. The money market appeared to be shutting down and there was a non-trivial chance that Western Capitalism was about to collapse. This, I felt, could almost certainly be avoided but we should not delude ourselves about the risks we faced.

In October of 2008 I advised North Carolina officials that they were about to see an unprecedented drop in retail sales and that this would lead to massive losses in sales tax revenue. Credit was being cut and households who were spending more than they took in were going to have adjust rapidly.

All of these things seemed to be confirmed by events and they were all based on a vulgar New Keynesian model of the economy with a special role for the financial sector. I didn’t think any of these forecasts were particularly prescient. Indeed, I thought I was simply translating the conventional wisdom. Apparently not.

Cochrane argues that economists should not have been able to predict this crash. However, it seems to me that much of it was predicted. Zingales and others have argued that the panic which gripped the Fed and Treasury actually precipitated the worst of the crisis. Academically I can’t rule this out.

There is a basic identification problem here. If one side thinks that panicking causes crises and the other thinks that foreseeing a crisis causes panic there might not be a lot we can do to sort this out, save for the type of randomized experiments we could never justify actually performing on real economies.

In short, what puzzles me is how different the views of esteemed economists were from a pedestrian analysis. If they are right why did things happen the way I and others thought they would happen? Were we just lucky? If we are right, how is it that Fama and Cochrane are missing basic points about the economy?

Scott Sumner’s column at Cato Unbound is a compelling read. I still get the feeling that Sumner and I may be thinking past one another. Sumner maintains that monetary policy was too tight in the Summer of 2008 and this lead directly to what I forecast as the “recession within a recession".”

I agree with this line thinking. In early 2008 I argued that the “there is no tightrope.” That is, that the Fed was unnecessarily concerning itself with inflation. This crisis was the first time I found myself less hawkish than the Fed. However, this dovishness was inspired by a feeling that a collapse in the financial sector would create an enormous increase in the demand for money.

I don’t see how thinking that the Fed was too tight is at odds with thinking that the popping of the credit bubble was behind the crash.

Looking back, I think I did fall prey to the notion that the Funds rate should be dropped in targeted bursts. Going straight to zero might have been a better plan. Yes, there is the fear of “spooking the market,” but sometimes we have much more to fear than fear itself.

What I found particularly intriguing, however, was Sumner’s proposal for a targeting Nominal GDP futures contracts. I am a bit of an institutional conservative, so a change this radical would make me very, very nervous but at first blush it seems to make a lot of sense.

One is essentially, “targeting expectations.” This seems like exactly what we want to do. I haven’t thought through exactly how this works with productivity shocks, however.

Suppose that in 2015 there are major nanotech breakthroughs and the economy begins to expand rapidly. This type of target would have the Fed step on the brakes pretty heavily. If technological growth were large enough it seems that the Fed would be required to generate unemployment, deflation or more likely a combination of both. So, I am not sure how we respond to that it Sumner’s framework.

Lastly, I think Jim Hamilton misread Sumner’s recommendation. Hamilton writes

Perhaps there are some more details of what Sumner has in mind that I am missing, but I don’t really understand how it could work. The essence of any Fed operation is an exchange of assets of equivalent value. Traditionally, the Fed uses the money it creates to purchase a T-bill, thereby increasing the quantity of money in circulation. However, a futures contract is not an asset, but instead is an agreement between two parties for which neither party initially compensates the other.

I don’t think Sumner is suggesting the Fed use future contracts as a tool of monetary policy. Presumably standard open market operations with t-bills would still work. Simply, that the Fed expand or contract the money supply such that future contract trades at the Fed’s target value.

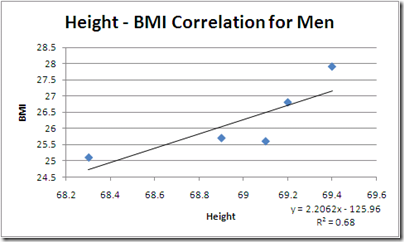

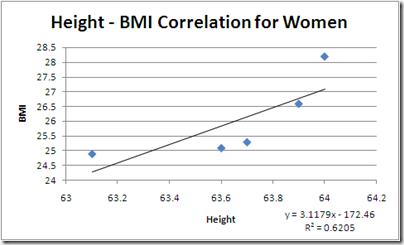

Here is something that I am embarrassed I didn’t catch before – the strong correlation between height and obesity in the NHANES data.

Even with a linear relationship the correlation is strong

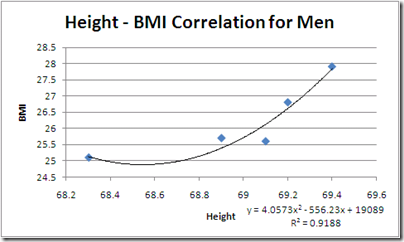

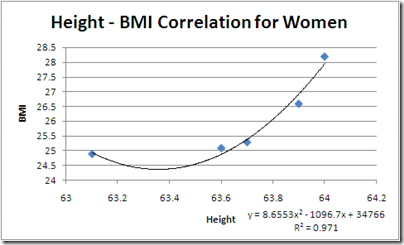

With a second order polynomial it becomes striking

What makes this particularly interesting is not only how tight the correlation is but that the two are currently negatively correlated in the cross sectional data but I suspect in the past they were positively correlated.

So one very naive interpretation is that you have a single driving force but that it manifests in some as height and in others as increased body mass. I hope to have more to say on this later this week, schedule permitting.

My best guess is that most insurance is bought not to reduce risk but instead to signal prudence and caring. The first life insurance companies had a terrible time selling "bets on their death," and only succeded when they framed insurance as what a caring and prudent husband and father did to take care of his family. While simple adverse-selection theories predict that high risk folks buy the most insurance, in fact low risk folks buy more insurance. And we don’t want to insure our big life risks because such a desire would signal a lack of confidence in our prospects.

Actually I always saw life insurance advertised as protection for the insured. Yet, of course, its protection for the survivors.

My assumption, however, was that people were using insurance as a talisman. I.E., if I would actually benefit financially from my spouse’s death than surely it won’t happen, because nothing ever happens to benefit me financially.

Sadly, I think most hedging is based on this principle.

Matt Latimer’s GQ exposé is one of the best reads of the year. Just about every paragraph is quotable gold but I will leave you with my favorite.

The set up: Latimer is a Bush speech writer in the final days of the administration. Bush is about to deliver a speech on announcing what will be the $700 Billion bailout and wants to know why Latimer’s draft speech didn’t explain that the government was buying low and selling high.

He repeated his belief that the government was going to “buy low and sell high,” and he still didn’t understand why we hadn’t put that into the speech like he’d asked us to. When it was explained to him that his concept of the bailout proposal wasn’t correct, the president was momentarily speechless. He threw up his hands in frustration.

“Why did I sign on to this proposal if I don’t understand what it does?” he asked.

The president was clearly frustrated with what was going on, but there was little he could do at this late hour. He went up to take a nap, saying he was beat. He looked it. I’d never seen him more exhausted. His hair was out of place and shaggy. His face looked drained and pale. Even more distressing, he was wearing Crocs. As I looked at him I thought to myself, how many more crises can one guy take?

HT: Yglesias

Ezra Klein opines on health care cost growth around the world.

Observers don’t get very excited about the fact that China’s economic growth is frequently three or four times what America enjoys. It doesn’t mean that China’s economy is three or four times better, or its model is somehow desirable. Rather, it’s in large part the function of having a low denominator. China’s economy is much smaller than ours, which means it has a lot more room to grow, and each dollar of expansion is larger in percent terms than it would be in the American economy.

So too with this Business Week graph showing health-care cost growth around the world. The author is quite surprised that the U.K.’s spending growth outpaces ours. But of course it does. The U.K. spends $2,992 per person. The U.S. spends $7,290 per person. To put this in real terms, the U.S.’s 5.8 percent growth works out to a $422 increase per person.

This reasoning is more or less wrong.

First, countries with low incomes don’t grow faster because the denominator is small or because each dollar makes a big impact. The denominator is small for much of Sub-Saharan Africa, where growth has been stagnant during the last 50 years. The denominator is small for North Korea. The denominator was relatively small during Latin America’s lost decade.

Countries with low incomes grow faster because there is conditional convergence. That is, countries with similar institutions and similar polices (perhaps also similar culture, though there is an identification problem here) will tend have the same income. This means the smaller ones grow faster and the bigger ones grow slower. This phenomenon is similar to reversion to the mean.

Likewise, it should not be obvious that the UK’s health care growth rate should be faster than the US. The UK has a radically different health care policy and different health care institutions. Thus, it is not clear that the UK should converge upon the US.

Indeed, one major argument for moving towards a more UK style health care policy is that on their current paths US and the UK will not converge and may even diverge. That is, even as health care spending grows globally, the US will always be more expensive that the UK and the gap might even widen.

If instead we think that the US and the UK are converging, then the idea that there are cost savings from switching to a more centralized system vanishes. If we look far enough into the future costs in the two countries will be basically the same.

Now, what is important is the rate of growth of the overall economy. If it is the case that the UKs economy was growing faster than the US over that period, then there could have been some convergence in terms of spending level but no convergence in terms of spending as a percent of GDP. That is the data that I would be more interested in seeing.

Via Casey Mulligan, Cochrane responds to Krugman’s NYT Magazine piece. What follows below is the full text of Cochrane’s response. Mulligan linked to it as a Word Document. I felt it would have more presence of the blogosphere as html. I am assuming that Cochrane would want his ideas spread to a wider audience.

How did Paul Krugman get it so Wrong?

John H. Cochrane[1]

Many friends and colleagues have asked me what I think of Paul Krugman’s New York Times Magazine article, “How did Economists get it so wrong?”

Most of all, it’s sad. Imagine this weren’t economics for a moment. Imagine this were a respected scientist turned popular writer, who says, most basically, that everything everyone has done in his field since the mid 1960s is a complete waste of time. Everything that fills its academic journals, is taught in its PhD programs, presented at its conferences, summarized in its graduate textbooks, and rewarded with the accolades a profession can bestow, including multiple Nobel prizes, is totally wrong. Instead, he calls for a return to the eternal verities of a rather convoluted book written in the 1930s, as taught to our author in his undergraduate introductory courses. If a scientist, he might be a global-warming skeptic, an AIDS-HIV disbeliever, a stalwart that maybe continents don’t move after all, or that smoking isn’t that bad for you really.

It gets worse. Krugman hints at dark conspiracies, claiming “dissenters are marginalized.” Most of the article is just a calumnious personal attack on an ever-growing enemies list, which now includes “new Keyenesians” such as Olivier Blanchard and Greg Mankiw. Rather than source professional writing, he plays gotcha with out-of-context second-hand quotes from media interviews. He makes stuff up, boldly putting words in people’s mouths that run contrary to their written opinions. Even this isn’t enough: he adds cartoons to try to make his “enemies” look silly, and puts them in false and embarrassing situations. He accuses us literally of adopting ideas for pay, selling out for “sabbaticals at the Hoover institution” and fat “Wall street paychecks.” It sounds a bit paranoid.

It’s annoying to the victims, but we’re big boys and girls. It’s a disservice to New York Times readers. They depend on Krugman to read real academic literature and digest it, and they get this schlock instead. And it’s ineffective. Any astute reader knows that personal attacks and innuendo mean the author has run out of ideas.

And that’s the biggest and saddest news of this piece: Paul Krugman has no interesting ideas whatsoever about what caused our current financial and economic problems, what policies might have prevented it, or what might help us in the future, and he has no contact with people who do. “Irrationality” and “spend like a drunken sailor” are pretty superficial compared to all the fascinating things economists are writing about it these days.

What do I think? How sad.

That’s what I think, but I don’t expect you the reader to be convinced by my opinion or my reference to professional consensus. Maybe he is right. Occasionally sciences, especially social sciences, do take a wrong turn for a decade or two. I thought Keynesian economics was such a wrong turn. So let’s take a quick look at the ideas.

Krugman’s attack has two goals. First, he thinks financial markets are “inefficient,” fundamentally due to “irrational” investors, and thus prey to excessive volatility which needs government control. Second, he likes the huge “fiscal stimulus” provided by multi-trillion dollar deficits.

Efficiency.

It’s fun to say we didn’t see the crisis coming, but the central empirical prediction of the efficient markets hypothesis is precisely that nobody can tell where markets are going – neither benevolent government bureaucrats, nor crafty hedge-fund managers, nor ivory-tower academics. This is probably the best-tested proposition in all the social sciences. Krugman knows this, so all he can do is huff and puff about his dislike for a theory whose central prediction is that nobody can be a reliable soothsayer.

Krugman writes as if the volatility of stock prices alone disproves market efficiency, and efficient marketers just ignored it all these years. This is a canard that Paul knows better than to pass on, no matter how rhetorically convenient. (I can overlook his mixing up the CAPM and Black-Scholes model, but not this.) There is nothing about “efficiency” that promises “stability.” “Stable” growth would in fact be a major violation of efficiency. Efficient markets did not need to wait for “the memory of 1929 … gradually receding,” nor did we fail to read the newspapers in 1987. Data from the great depression has been included in practically all the tests. In fact, the great “equity premium puzzle” is that if efficient, stock markets don’t seem risky enough to deter more people from investing! Gene Fama’s PhD thesis was on “fat tails” in stock returns.

It is true and very well documented that asset prices move more than reasonable expectations of future cashflows. This might be because people are prey to bursts of irrational optimism and pessimism. It might also be because people’s willingness to take on risk varies over time, and is sharply lower in bad economic times. As Gene Fama pointed out in 1972, these are observationally equivalent explanations at the superficial level of staring at prices and writing magazine articles and opeds. Unless you are willing to elaborate your theory to the point that it can quantitatively describe how much and when risk premiums, or waves of “optimism” and “pessimism,” can vary, you know nothing. No theory is particularly good at that right now. Crying “bubble” is no good unless you have an operational procedure for identifying bubbles, distinguishing them from rationally low risk premiums, and not crying wolf too many years in a row.

But this difficulty is really no surprise. It’s also the central prediction of free-market economics, as crystallized by Hayek, that no academic, bureaucrat or regulator will ever be able to fully explain market price movements. Nobody knows what “fundamental” or “hold to maturity value” is. If anyone could tell what the price of tomatoes should be, let alone the price of Microsoft stock, communism would have worked.

More deeply, the economist’s job is not to “explain” market fluctuations after the fact, to give a pleasant story on the evening news about why markets went up or down. Markets up? “A wave of positive sentiment.” Markets went down? “Irrational pessimism.” (And “the risk premium must have increased” is just as empty.) Our ancestors could do that. Really, is that an improvement on “Zeus had a fight with Apollo?” Good serious behavioral economists know this, and they are circumspect in their explanatory claims so far.

But this argument takes us away from the main point. The case for free markets never was that markets are perfect. The case for free markets is that government control of markets, especially asset markets, has always been much worse. Free markets are the worst system ever devised – except for all of the others.

Krugman at bottom is arguing that the government should massively intervene in financial markets, and take charge of the allocation of capital. He can’t quite come out and say this, but he does say “Keynes considered it a very bad idea to let such markets…dictate important business decisions,” and “finance economists believed that we should put the capital development of the nation in the hands of what Keynes had called a `casino.’” Well, if markets can’t be trusted to allocate capital, we don’t have to connect too many dots to imagine who Paul has in mind.

To reach this conclusion, you need theory, evidence, experience, or any realistic hope that the alternative will be better. Remember, the SEC couldn’t even find Bernie Madoff when he was handed to them on a silver platter. Think of the great job Fannie, Freddie, and Congress did in the mortgage market. Is this system going to regulate Citigroup, guide financial markets to the right price, replace the stock market, and tell our society which new products are worth investment? As David Wessel’s excellent In Fed We Trust makes perfectly clear, government regulators failed just as abysmally as private investors and economists to see the storm coming. And not from any lack of smarts.

In fact, the behavioral view gives us a new and stronger argument against regulation and control. Regulators are just as human and irrational as market participants. If bankers are, in Krugman’s words, “idiots,” then so must be the typical treasury secretary, fed chairman, and regulatory staff. They act alone or in committees, where behavioral biases are much better documented than in market settings. They are still easily captured by industries, and face horrendously distorted incentives.

Careful behavioralists know this, and do not quickly run from “the market got it wrong” to “the government can put it all right.” Even my most behavioral colleagues Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their book “Nudge” go only so far as a light libertarian paternalism, suggesting good default options on our 401(k) accounts. (And even here they’re not very clear on how the Federal Nudging Agency is going to steer clear of industry capture.) They don’t even think of jumping from irrational markets, which they believe in deeply, to Federal control of stock and house prices and allocation of capital.

Stimulus

Most of all, Krugman likes fiscal stimulus. In this quest, he accuses us and the rest of the economics profession of “mistaking beauty for truth.” He’s not that clear on what the “beauty” is that we all fell in love with, and why one should shun it. And for good reason. The first siren of beauty is simple logical consistency. Paul’s Keynesian economics requires that people make plans to consume more, invest more, and pay more taxes with the same income. The second siren is even vaguely plausible assumptions about how people behave. Keynesian economics requires that the government is able to systematically fool people again and again. It presumes that people don’t think about the future in making decisions today. Logical consistency and vaguely plausible foundations are indeed “beautiful” but to me they are also basic preconditions for “truth.”

In economics, stimulus spending ran aground on Robert Barro’s Ricardian equivalence theorem. This theorem says that debt-financed spending can’t have any effect because people, seeing the higher future taxes that must pay off the debt, will simply save more. They will buy the new government debt and leave all spending decisions unaltered. Is this theorem true? It’s a logical connection from a set of “if” to a set of “therefore.” Not even Paul can object to the connection.

Therefore, we have to examine the “ifs.” And those ifs are, as usual, obviously not true. For example, the theorem presumes lump-sum taxes, not proportional income taxes. Alas, when you take this into account we are all made poorer by deficit spending, so the multiplier is most likely negative. The theorem (like most Keynesian economics) ignores the composition of output; but surely spending money on roads rather than cars can affect the overall level.

Economists have spent a generation tossing and turning the Ricardian equivalence theorem, and assessing the likely effects of fiscal stimulus in its light, generalizing the “ifs” and figuring out the likely “therefores.” This is exactly the right way to do things. The impact of Ricardian equivalence is not that this simple abstract benchmark is literally true. The impact is that in its wake, if you want to understand the effects of government spending, you have to specify why it is false. Doing so does not lead you anywhere near old-fashioned Keynesian economics. It leads you to consider distorting taxes, estate taxes, how much people care about their children, how many people would like to borrow more to finance today’s consumption and so on. And when you find “market failures” that might justify a multiplier, that analysis quickly suggests direct fixes for the market failures, not their exploitation along the lines Keynes suggested. Most “New Keynesian” analysis that add frictions don’t produce big multipliers.

This is how real thinking about stimulus actually proceeds. Nobody ever “asserted that an increase in government spending cannot, under any circumstances, increase employment.” This is unsupportable by any serious review of professional writings, and Krugman knows it. (My own are perfectly clear on lots of possibilities for an answer that is not zero.) But thinking through this sort of thing and explaining it is so much harder than just tarring your enemies with out-of-context quotes, ethical innuendo, or silly cartoons.

In fact, I propose that Krugman himself doesn’t really believe the Keynesian logic for that stimulus. I doubt he would follow that logic to its inevitable conclusions. Stimulus must have some other attraction to him.

If you believe the Keynesian argument for stimulus, you should think Bernie Madoff is a hero. Seriously. He took money from people who were saving it, and gave it to people who most assuredly were going to spend it. Each dollar so transferred, in Krugman’s world, generates an additional dollar and a half of national income. The analogy is even closer. Madoff didn’t just take money from his savers, he really borrowed it from them, giving them phony accounts with promises of great profits to come. This looks a lot like government debt.

If you believe the Keynesian argument for stimulus, you don’t care how the money is spent. All this puffery about “infrastructure,” monitoring, wise investment, jobs “created” and so on is pointless. Keynes thought the government should pay people to dig ditches and fill them up.

If believe in Keynesian stimulus, you don’t even care if the government spending money is stolen. Actually, that would be better. Thieves have notoriously high propensities to consume.

The crash.

Krugman’s article is supposedly about how the crash and recession changed our thinking, and what economics has to say about it. The most amazing piece of news in the whole article is that Paul Krugman has absolutely no idea about what caused the crash, what policies might have prevented it, and what policies we should adopt going forward. Furthermore, he seems completely unaware of the large body of work by economists who actually do know something about the banking and financial system, and have been thinking about it productively for a generation.

Here’s all he has to say: “Irrationality” caused markets to go up and then down. “Spending” then declined, for unclear reasons, possibly “irrational” as well. The sum total of his policy recommendations is for the Federal Government to spend like a drunken sailor after the fact.

Paul, there was a financial crisis, a classic near-run on banks. The centerpiece of our crash was not the relatively free stock or real estate markets, it was the highly regulated commercial banks. A generation of economists has thought really hard about these kinds of events. Look up Diamond, Rajan, Gorton, Kashyap, Stein, and so on. They’ve thought about why there is so much short term debt, why banks run, how deposit insurance and credit guarantees help, but how they give incentives for excessive risk taking.

If we want to think about events and policies, this seems like more than a minor detail. The hard and central policy debate over the last year was how to manage this financial crisis. Now it is how to set up the incentives of banks and other financial institutions so this mess doesn’t happen again. There’s lots of good and subtle economics here that New York Times readers might like to know about. What does Krugman have to say? Zero.

Krugman doesn’t even have anything to say about the Fed. Ben Bernanke did a lot more last year than set the funds rate to zero and then go off on vacation and wait for fiscal policy to do its magic. Leaving aside the string of bailouts, the Fed started term lending to securities dealers. Then, rather than buy treasuries in exchange for reserves, it essentially sold treasuries in exchange for private debt. Though the funds rate was near zero, the Fed noticed huge commercial paper and securitized debt spreads, and intervened in those markets. There is no “the” interest rate anymore, the Fed is managing them all. Recently the Fed has started buying massive quantities of mortgage-backed securities and long-term treasury debt.

Monetary policy now has little to do with “money” vs. “bonds” with all the latter lumped together. Monetary policy has become financial policy. Does any of this work? What are the dangers? Can the Fed stay independent in this new role? These are the questions of our time. What does Krugman have to say? Nothing.

Or perhaps Krugman’s point is that a cabal of obvious crackpots bedazzled all of macroeconomics with the beauty of their mathematics, to the point of inducing policy paralysis. Alas, that won’t stick. The sad fact is that few in Washington pay the slightest attention to neo-classical or intertemporal ideas. Paul’s simple Keynesianism has dominated policy analysis for decades and continues to do so. From the CEA to the Fed to the OMB and CBO, everyone just adds up consumer, investment and government “demand” to forecast output and uses simple Phillips curves to think about inflation. If a failure of ideas caused bad policy, it’s Keynes’ ideas that failed.

The future of economics.

How should economics change? Krugman argues for three incompatible changes.

First, Krugman argues for a future of economics that “recognizes flaws and frictions,” and incorporates alternative assumptions about behavior, especially towards risk-taking. To which I say, “Hello, Paul, where have you been for the last 30 years?” Macroeconomists have not spent 30 years admiring the eternal verities of Kydland and Prescott’s 1982 paper. Pretty much all we have been doing for 30 years is introducing flaws, frictions and new behaviors, especially new models of attitudes to risk, and comparing the resulting models, quantitatively, to data. The long literature on financial crises and banking which Krugman does not mention has been doing exactly this bidding for the same time.

Second, Krugman argues that “a more or less Keynesian view is the only plausible game in town,” and “Keynesian economics remains the best framework we have for making sense of recessions and depressions.” One thing is pretty clear by now, that when economics incorporates flaws and frictions, the result will not be to rehabilitate an 80-year-old book. As Paul bemoans, the “new Keynesians” who did just what he asks, putting Keynes inspired price-stickiness into logically coherent models, ended up with something that looked a lot more like monetarism. (Actually, though this is the consensus, my own work finds that new-Keynesian economics ended up with something much different and more radical than monetarism.) A science that moves forward almost never ends up back where it started. Einstein revises Newton, but does not send you back to Aristotle. At best you can play the fun game of hunting for inspirational quotes, but that doesn’t mean much.

Third, and most surprising, is Krugman’s Luddite attack on mathematics; “economists as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth.” Models are “gussied up with fancy equations.” I’m old enough to remember when Krugman was young, working out the interactions of game theory and increasing returns in international trade, and the old guard tut-tutted “nice recreational mathematics, but not real-world at all.” How quickly time passes.

Again, what is the alternative? Does Krugman really think we can make progress on his – and my – agenda for economic and financial research — understanding frictions, imperfect markets, complex human behavior, institutional rigidities – by reverting to a literary style of exposition, and abandoning the attempt to compare theories quantitatively against data? Against the worldwide tide of quantification in all fields of human endeavor (read “Moneyball”) is there any real hope that this will work in economics?

No, the problem is that we don’t have enough math. Math in economics serves to keep the logic straight, to make sure that the “then” really does follow the “if,” which it so frequently does not if you just write prose. The challenge is how hard it is to write down explicit artificial economies with these ingredients, actually solve them, in order to see what makes them tick. Frictions are just bloody hard with the mathematical tools we have now.

The insults.

The level of personal attack in this article, and fudging of the facts to achieve it, is simply amazing.

As one little example (ok, I’m a bit sensitive), take my quotation about carpenters in Nevada. I didn’t write this. It’s a quote, taken out of context, from a bloomberg.com article written by a rather dense reporter who I spent about 10 hours with patiently trying to explain some basics. (It’s the last time I’ll do that!) I was trying to explain how sectoral shifts contribute to unemployment. Krugman follows it by a lie — I never asserted that “it take mass unemployment across the whole nation to get carpenters to move out of Nevada.” You can’t even dredge up a quote for that monstrosity.

What’s the point? I don’t think Paul disagrees that sectoral shifts result in some unemployment, so the quote actually makes sense as economics. The only point is to make me, personally, seem heartless — a pure, personal, calumnious attack, having nothing to do with economics.

Bob Lucas has written extensively on Keynesian and monetarist economics, sensibly and even-handedly. Krugman chooses to quote a joke, made back in 1980 at a lunch talk to some business school alumni. Really, this is on the level of the picture of Barack Obama with Bill Ayres that Sean Hannity likes to show on Fox News.

It goes on. Krugman asserts that I and others “believe” “that an increase in government spending cannot, under any circumstances, increase employment,” or that we “argued that price fluctuations and shocks to demand actually had nothing to do with the business cycle.” These are just gross distortions, unsupported by any documentation, let alone professional writing. And Krugman knows better. All economic models are simplified to exhibit one point; we all understand the real world is more complicated; and his job is supposed to be to explain that to lay readers. It would be no different than if we were to look up Paul’s early work which assumed away transport costs and claim “Paul Krugman believes ocean shipping is free, how stupid” in the Wall Street Journal.

Of course the idea that any of us do what we do because we’re paid off by fancy Wall Street salaries or cushy sabbaticals at Hoover is just ridiculous. (If Krugman knew anything about hedge funds he’d know that believing in efficient markets disqualifies you for employment. Nobody wants a guy who thinks you can’t make any money trading!) And given Krugman’s speaking fees and how much the looney right likes him, it’s a surprising first stone for him to cast.

Apparently, salacious prose, ethical innuendo, calumny, and selective quotation from media aren’t enough: Krugman added cartoons to try to make opponents look silly. The Lucas-Blanchard-Bernanke conspiratorial cocktail party celebrating the end of recessions is a fiction. So is their despondent gloom on reading “recession” in the paper. Nobody at a conference looks like Dr. Pangloss with wild hair and a suit from the 1800s. (OK, Randy Wright has the hair, but not the suit.) Keynes did not reappear at the NBER to be booed as an “outsider.” Why are you allowed to make things up in pictures that wouldn’t pass even the Times’ weak fact-checking in words?

Well, perhaps we got off easy. This all was mild compared to Krugman’s vicious obituary of Milton Friedman in the New York Review of Books. But most of all, Paul isn’t doing his job. He’s supposed to read, explain, and criticize things economists write, and preferably real professional writing, not interviews, opeds and blog posts. At a minimum, this leads to the unavoidable conclusion that Krugman simply isn’t reading real economics anymore. Well, the equations are hard. But most of all, who cares about Paul’s character assassination attempts of us boring and politically unimportant academics?

How did Krugman get it so wrong?

So what is Krugman up to? Why become a denier, a skeptic, an apologist for 70 year old ideas, replete with well-known logical fallacies, a pariah? Why publish an essentially personal attack on an ever-growing enemies list that now includes practically every professional economist? Why publish an incoherent vision for the future of economics?

The only explanation that makes sense to me is that Krugman isn’t trying to be an economist, he is trying to be a partisan, political opinion writer. This is not an insult. I read George Will, Charles Krauthnammer and Frank Rich with equal pleasure even when I disagree with them. Krugman wants to be Rush Limbaugh of the Left. I still want to be Milton Friedman, but each is a worthy calling.

Alas, to Krugman, as to far too many ex-economists in partisan debates, economics is not a quest for understanding. It is a set of debating points to argue for policies that one has adopted for partisan political purposes. “Stimulus” is just marketing with which to sell voters on a package of government spending priorities that you want for political reasons. It’s not a proposition to be explained, understood, taken seriously to its logical limits, or reflective of market failures that should be addressed directly. To my mind, Krugman left the world of economics when, in the California electricity crisis, he argued that supply curves slope down; that a price cap, desired by his political constituency, would increase electricity supplies. That position served the political goal no matter how tortured the economics. This is more of the same.

Why argue for a nonsensical future for economics? Well, again, if you don’t regard economics as a science, a discipline that ought to result in quantitative matches to data, a discipline that requires crystal-clear logical connections between the “if” and the “then,” if the point of economics is merely to provide marketing and propaganda for politically-motivated policy, then it all does make sense. It makes sense to appeal to some future economics – not yet worked out, even verbally –disdain quantification and comparison to data, and to appeal to the authority of ancient books as interpreted you, their lone remaining apostle.

Most of all, this is the only reason I can come up with to understand why Krugman wants to write personal attacks on those who disagree with him. I like it when people disagree with me, and take time to read my work and criticize it. At worst I learn how to position it better. At best, I discover I was wrong and learn something. I send a polite thank you note.

Krugman wants people to swallow his arguments whole from his authority, without demanding logic, or evidence. Those who disagree with him, alas, are pretty smart and have pretty good arguments if you bother to read them. So, he tries to discredit them with personal attacks.

This is the political sphere, not the intellectual one. Don’t argue with them, swift-boat them. Find some embarrassing quote from an old interview. Well, good luck, Paul. Let’s just not pretend this has anything to do with economics, or actual truth about how the world works or could be made a better place.

[1] University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Many colleagues and friends helped, but I don’t want to name them for obvious reasons. Please don’t bother emailing me to tell me what a jerk I am.

. . . to win an election but lose its own ideology.

Ezra Klein points to the contradiction between this video

and the alternative GOP budget. He mocks the lack of message discipline but my criticism is much deeper. What exactly is the long term plan here? Suppose you win the mid-terms based on an appeal to preserving Medicare. What then?

The GOP has made smaller government and lower taxes the cornerstone of its platform. Yet, we all know that government will grow and taxes will rise if Medicare continues in its current form.

Doesn’t this type of advertising undermine the basic goals of your own party? Doesn’t it push the GOP vision for America further away? Why do this?

Perhaps they have in mind a grand tilt, where the GOP moves away from being a party of small government and simply a party of conservative social values no matter what your fiscal beliefs are.

A great deal has been written on the state of macroeconomics as a discipline in the last few weeks and I hope to respond to much of it. However, let me start with Scott Sumner.

Here is a puzzle. Almost everything we have learned from recent research in monetary history, theory, and policy points to the Federal Reserve as the cause of the crash of late 2008. More specifically, an extremely tight monetary policy in the US (and perhaps Europe and Japan) seems to have sharply depressed nominal spending after July 2008. And yet it is difficult to find economists who believe this. More surprisingly, few economists are even aware that their views conflict with the standard model, circa 2009.

Its not completely clear where Sumner’s views and my own part ways. Sumner says that the Fed was “too tight.”

To counter evidence to the contrary he argues that looking at interest rates is misleading. Low interest rates can imply low inflation and hence tight money. He says that looking at the monetary base is misleading, as it ignores changes in reserve regulations. In 2008 the Fed began to pay interest on reserves. So far this seems right..

He then, however, goes on to say that

If we learned anything from the 1980s, it is that the broader aggregates are no more reliable than the base. During financial turmoil, it is not surprising that there is an increased demand for safe, FDIC-insured bank deposits.

Now this sounds to me as if Sumner is simply saying that the crisis on Wall Street lead to a rapid increase in money demand. Its not clear to me how this is different than the standard view. The turmoil created flight to quality which drove people out of risky assets and into cash and Treasuries. In an attempt to horde cash businesses and consumers cut purchases and induced a recession.

In this story the chain of events starts with “the turmoil.” It wasn’t that the Fed tightened and thus money was too tight. It was that money demand soared and thus money became effectively tight.

The Fed then had two avenues for “loosening” monetary policy. One, it could simply expand the money supply as Sumner suggests. However, it was not clear that this would be effective at the zero lower bound. Sumner argues that it would be but I think at a minimum we can say there is no consensus that traditional monetary policy is effective at the zero lower bound.

Two, the Fed could attempt to alleviate money demand. Since, the increase in money demand was driven by fears about bank failures the Fed could move to secure the banking system. Once, the public became sure that the system would survive money demand would return to normal and policy would no longer be tight. This seems to be the path the Fed chose and it seems to have been effective.

However, Sumner discounts the second avenue by suggesting that tight money caused the bank failures.

After the failure of Lehman most economists simply assumed that causation ran from financial crisis to falling demand. This reversed the primary direction of causation – as in the Great Depression, economic weakness worsened bank balance sheets and intensified the financial crisis in late 2008.

How then do we explain money that was “too tight for the needs of the economy” when the money supply was increasing? It seems that Sumner has in mind some sort of contraction starting in early 2008. However, the financial crisis began in the summer of 2007. It seems much more straight forward that money demand had been increasing since the first spike in the Funds rate in August 2007. Perhaps, had the Fed responded more aggressively the crisis could have been muted. Perhaps, increase the quantity of money at the zero lower bound would have worked. But, I don’t see how the crisis was started by the Fed.

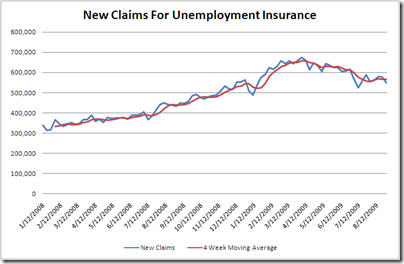

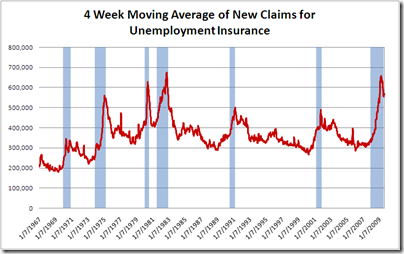

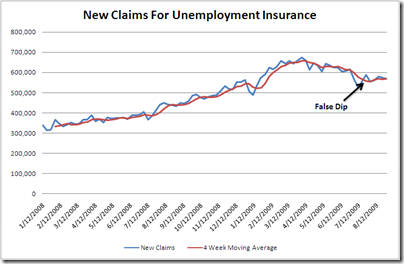

New Claims for unemployment insurance fell to 550K this week from a revised 576K. That’s a substantial dip but it does little to change the overall picture. The four week moving average moved down just 1K from 568K to 567K. This is still above the 560K four week average from a month ago.

The big picture is of an economy that is improving very slowly and each new week has served only to confirm that image. Indeed, we are moving closer and closer to an outright stall.

The diet drug Qnexa blew away clinical trials with a mean weight loss of 37 pounds in high dose patients who completed the one year clinical trial. 84% of high does patients who completed lost 5% of body weight or more at the end of the year.

This should not be a surprise given the success of fen-phen which uses the same stimulant (the phen) but a different partner (the fen).

It is worth noting that Qnexa outperformed Contrane. I know that the food addiction theory of obesity is becoming popular and Contrane combines two anti-addiction drugs, buproprion (Zyban) and naltrexone (ReVia). Whereas, Qxena contains a direct appetite suppressant and a blood sugar regulator.

What is particularly telling is that Qnexa seems to treat all of metabolic syndrome. Lower BMI, lower blood sugar, higher HDL. Note that fat removal via surgery does not treat metabolic syndrome. I take this as evidence that it is more likely that metabolic syndrome produces obesity rather than obesity producing metabolic syndrome.

Obviously no one is going to let me run this trial but I am dying to see what happens when we combine Qnexa with an extremely high-fat or extremely high-glycemic diet. When it becomes commercially available we will no doubt have anecdotal evidence on this.

Lots of bloggers have linked to a New Yorker piece which suggests that Texas may become the first state to admit that it has executed an innocent man.

I emphasize admit because my priors make me highly skeptical that anyone has designed and is operating a system with a zero fail rate, particularly at the relatively low cost that our legal systems operates at.

Prosecuting a capital case costs an estimated $2.3 million. This may seem like a lot but is actually pretty trivial sum when you are trying to design a system that never – ever executes innocent people, but does manage to execute some reasonable fraction of guilty people. I am willing to be convinced but I don’t see that funding the heavy detail work of examining each piece of evidence, not only to verify its authenticity but that no false assumptions or mistakes of reason were made in any previous analysis.

My understanding is the primary error checking means in capital cases is to make sure their were no procedural errors. However, in a situation where the outcome is binary – guilty or not – aggressive error correction would make sure that you could get the same result using multiple distinct methods. To my knowledge this is not done at all.

In addition, it seems that the heinous of the crime is a factor determining whether or not the death penalty is applied. This seems exactly wrong from an error correction perspective. Humans are less likely to be completely objective in situations where they are deciding about a highly emotional issue.

Perhaps most disconcertingly, there seems to be very little accountability. If a jury member votes to execute someone and it is later discovered that they are innocent there seems to be no external price that the jury member pays.

I am sure that the jury member would feel bad about this. However, we don’t typically rely on people’s guilt to ensure that large errors aren’t made. If I run over you in my car then I expose myself to a charge of manslaughter and possibly a wrongful death suit.

Now, if I have done everything “right” I might not loose either case. Nonetheless, I still run the risk. Even if its only subconscious this accountability system makes me more cautious when I drive.

Now all of this focus error correction assumes that the most important thing is to avoid executing innocent people. This may or may not make sense when we balance against the possibility of deterring crime. However, I am shocked that people who seem to believe this is important nonetheless support the system.

So I found this

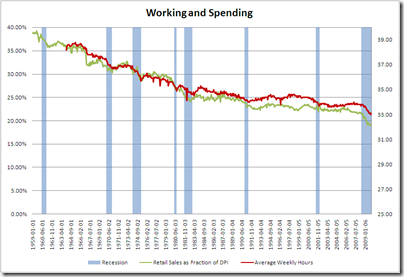

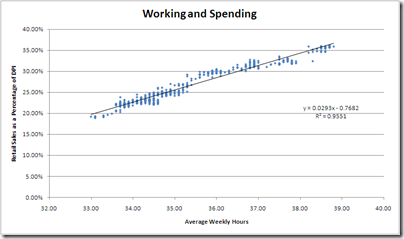

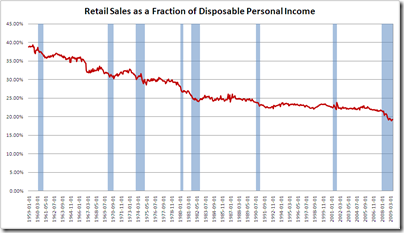

There seems to be a pretty tight correlation between retail sales as a fraction of disposable personal income (left axis) and the average weekly hours worked (right axis).

In the long run they are both declining, of course, but its not immediately clear why they should be declining at proportional rates. Over the business cycle it makes sense if there is causation running from consumption to hours work. People try to save more and additional savings leads to less work.

It makes less sense if the correlation is running from optimal hours worked to spending. In that case we would expect consumption to fall during downturns, people are choosing less work which leads to less income which leads to less consumption. However, consumption smoothing would suggest that consumption as a fraction of income should rise. In this graph our proxies for consumption spending as a fraction of income falls.

Now it could be that consumption is smoothed through non-retail channels: health care, service streams from existing housing and durables, etc. I am not sure, however, that when all the i’s are dotted and t’s crossed that this is theoretically consistent.

Here are the correlations

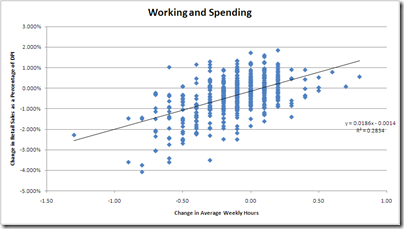

and the first difference

Following up on Yglesias’s post on consumption and Derek Thompson’s post on consumer spending, I took a look at retail sales as a fraction of disposable personal income. It hardly tells a tale of Americans rushing out to buy flat screens.

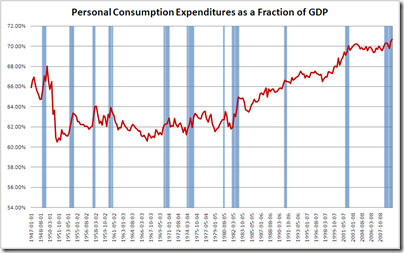

Contrast that with

Was all of the consumption binge health care? Imputed financial services? Stocks and Bonds? Right off I don’t know how to square this.

I take Megan McArdle’s argument that public health insurance will lead to cramdown of pharma profits seriously. I’m also sympathetic to the her views on the ill effects of such a cramdown, in part because pharmaceuticals are the only element of the medical industry that I am particularly sympathetic to.

I tend to think many, if not most, doctors serve primarily has human databases. As such I think they’re roughly as anachronistic as real estate agents. However, it will be some time before most Americans are comfortable getting their medical advice from a internet database operated by a licensed medical diagnostic technician. Until such time we’ll have to put up with spending billions of dollars to crowbar nearly a million, otherwise very productive, human brains into doing what a computer does effortlessly.

I am similarly not ultra-keen on a lot of the latest specialized medical technology because the cost to treat is often so high. Its one thing when you spend a bunch of money on the R&D but then each treatment is close to free. In that case you can hand out the treatment in every instance that you think its likely to do more harm than good. You might even find out its useful for things you didn’t think of before.

However, when every single treatment costs a ton of money to perform it can become a parasitic drain. You thought you were developing the treatment to treat X. And for X its worth money. However, now that its here everyone and their cousin wants to use it for Y and Z and there is no way to justify that expense. Unfortunately, there is also very little room to say no.

Drugs of course are often cheap to produce once you’ve gotten past the R&D. Not in every case of course, but its my understanding that this is the basic model. The plethora of low cost generics certainly seems to imply that this is the case. Thus, I am quite optimistic about the potential for pharmaceuticals to revolutionize our lives and to produce cost effective treatments for what ails us.

The questions is: suppose I can’t have cost controls on the rest of medicine without also imposing cost controls on pharmaceuticals. Drugs are good, but are they good enough to justify the rest of the bloated medical apparatus? Are they good enough to justify the collateral damage to the federal budget – the hundreds of programs that will be downsized as congress tries to limit the inevitable rise in taxes?

Its not at all clear to me that this is the case. Its not clear that arguments that the pharmaceutical industry is clearly marginally socially productive mean that the sum total of an effort to avoid government rationing is socially productive.

I highly doubt that with the pharmaceutical industry suppressed, new drug creation will grind to a halt. Public agencies will continue to work on drugs, although with unknown productiveness. And, if things get really bad I imagine there will be public pressure to allow a “reasonable” margin of profit in the drug industry, and perhaps some accounting changes such that intangible deprecation will reduce their reported profit margins.

I see Megan’s point but I’m just not sure its worth stopping the entire effort over.

Felix Salmon on Money Market Accounts