You are currently browsing the monthly archive for July 2010.

Some commenters have been pushing back against my suggestion that immigration can fix our housing “unemployment” problem. In fact, a decline in immigration is a partly to blame for our current vacancy problem. Here is the 2010 State of the Nation’s Housing from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, emphasis mine:

The stubbornly high and rising overall vacancy rate—even with production near 60-year lows—reflects the fact that household growth has been running well below what would be expected in normal economic times. While there is some evidence that doubling up in shared quarters has been on the increase, the main explanation for the weakness of demand appears to be lower net immigration.

The connection between immigration and housing demand is fairly obvious: they need somewhere to live. I’m surprised that there is any disagreement here, but there you have it in any case.

We should be doing what we can to reverse this trend by removing barriers to immigration. Foreclosures generate externalities via decreasing neighboring properties, and they destroy credit, which is a real asset of households. Increasing nominal house prices would have positive real effects on the economy right now, and we are ignoring an obvious lever that we could and should be pushing on. In addition, vacant properties are “unemployed” resources, which is a problem all by itself.

The Economist has quite clear chart showing the decadal average temperatures from the 1850’s to today.

The obvious thing to note is that temperatures have risen fairly dramatically throughout the 20th century. But another interesting thing that this chart shows is a very large increase in technology giving us greater precision in measurement happening in the 1950’s. You can see this by the shortening of the error bars that happen after that time.

…at least not in public.

For labor, the recalculation story says that employment is a by-product of patterns of specialization and trade.

Someone who openly admits that labor is an (unfortunate) by-product of economic activity, and not a desirable end in-and-of itself? Kudos!

Of course, I don’t suppose you get bribed into getting off your X-Box, driving across town, and doing a repetitive task for a set amount of time…do you?

In response to those who claim that people will “hoard rebates or cash”, Bryan Caplan writes:

Why are [people] saving in the first place? Once again, there are two theories:

Theory #1: People just don’t have anything they want to buy. They’re satiated, so no matter how much extra income they get, they’ll just sit on it.

Theory #2: People want a buffer. They aren’t comfortable with their current asset cushion, so they’re saving in order to return to their comfort zone.

Theory #1 is wholely implausible. There’s tons of stuff that people still covet. The truth, then, lies in Theory #2: People will start spending again once they feel like they’ve got enough breathing room.

If theory #2 is the truth, then there is no situation in which “helicopter drops” could fail to boost demand, save for a puzzling situation where we run out of gasoline, or paper and ink…but then again, just put some zeros behind peoples’ bank account balances. That doesn’t even require a helicopter!

And if it doesn’t work the second time, take another flight. And another. At some point, people will no longer demand excess cash balances, and will begin spending like crazy. If the Fed credibly commits to permanently increasing the monetary base in this way, it would certainly change NGDP expectations.

P.S. This logic only works for “helicopter drops”, with dubious effectiveness for tax rebates (you can’t credibly commit to cutting taxes forever, after all). Also: no, I don’t think this is an optimal solution to recessions.

Again, the data in this Figure do not mix at all its boxes on the right [US] and circles on the left [Japan]. But the most recent observation for the U.S., the solid box labelled May 2010,is about as close as the U.S. has been in recent times to the low nominal interest rate steady state. It is below the rate at which policy turns passive in the diagram. In addition, the FOMC has pledged to keep the policy rate low for an extended period.This pledge is meant to push ination back toward target certainly higher than where it is today thus moving to the right in the Figure. Still, as the Figure makes clear, pledging to keep the policy rate near zero for such a long time would also be consistent with the low nominal interest rate steady state in which ination does not return to target but instead both actual and expected ination turn negative and remain there. Furthermore, we have an example of an important economy which appears to be in just this situation.

How might one get out of such a deflationary expectations trap? By credibly committing to an expansionary monetary policy. That Japan has had near-zero rates for an extended period of time shows that it has failed to credibly commit to an expansionary monetary policy. One could say that they are in a “trap”…but for a decade? Please.

The policymaker is completely committed to interest rate adjustment as the main tool of monetary policy, even long after it ceases to make sense (long after policy becomes passive), creating a second steady state for the economy. Many of the responses to this situation described below attempt to remedy this situation by recommending a switch to some other policy in cases when ination is far below target. The regime switch required has to be sharp and credible policymakers have to commit to the new policy and the private sector has to believe the policymaker.

Unfortunately, in actual policy discussions nothing of this sort seems to be happening.

Bullard goes on to give possible explanations for the Fed remaining passive in the face of a dangerous deflationary risk:

- Denial: Japan’s experience was unique to some feature of Japan itself, and cannot happen in the US. But perhaps we have quirky features as well?

- Stability: We should be content with any given “steady state” equilibrium, for stability sake. This is what I believe happened in Japan.

- FOMC, 2003: A false sense of security provided by the reaction to “low interest rates for an extended period” the last time the US faced a deflationary risk.

And lest you wish to rest on your old Keynesian laurels:

This advice was given in the context of trying to preserve the desirable qualities of the Taylor-type interest rate rule in the neighborhood of the targeted steady state. That is, even though interest rate rules are the problem here, the advice is given in the context of not simply abandoning interest rate rules altogether.

The advice has a certain structure. It involves not changes to the way monetary policy is implemented, but changes in the fi scal stance of the government. By itself, this makes the practicality of the solution much more questionable.[…]

The described solution has the following favor: The government threatens to behave unreasonably if the private sector holds expectations (such as expectations of very low ination) that the government does not desire. This threat, if it is credible, eliminates the undesirable equilibrium. Some authors have criticized this type of solution to problems with multiple equilibria as unsophisticated implementation.*

[H/T Kevin Drum]

*Sophisticated Monetary Policies; Atekson, Chari, Kehoe

Alex Tabarrok draws an interesting analogy between home vacancies and unemployment, pointing out that vacant homes are just unemployed resources. He also provides this chart:

Unlike human unemployment, this is a problem with a really easy fix. It’s actually a fix that doesn’t require government spending, includes a bit of non-government Keynesian spending, and will help with our debt as well as lower global poverty. Right now, there are millions and millions of people who want to “employ” our “unemployed” housing stock: immigrants. Simply let more of them in and they will buy, rent, and live in these empty homes.

Can you imagine if a such a simple solution existed for any other resource underutilization problem that was having a huge negative impact on the wider economy, and not only were politicians not discussing it, but people aren’t demanding it. What is going on here?

Economics 21 has a pretty concise takedown on why Elizabeth Warren should not serve as chair of the Consumer Financial Protection Agency. It highlights concerns about her work on family income and bankruptcy, as well as her position on bank nationalization. Here, Adam, has been critical of her position on high interest lending as well.

Across the blogosphere her defenders have scrambled to poke holes in all of those arguments. My take: E. Warren is no fool. I don’t think she publishes hack reports and I have little doubt that there is a fair defense of her methodology.

That having been said, Paul Krugman is no fool either. He comes to the table with some of the most trenchant analysis available. However, I wouldn’t want Paul chairing the Commission on Partisan Bias. Paul has strong priors and the intellect to defend them. However – and I know I am risking a smack down from Delong – one cannot help but walk away from Paul’s writing feeling that he has been too clever by half when it comes to his take on partisan issues.

You know that Paul is smarter you. You know that his data instincts are keen. Yet, you also know that confirmation bias is real and that as such strong priors and formidable analytical skills can be a dangerous mix. Few people are sharp enough to poke holes in his argument and despite his best intentions he is not going to be able to reliably poke holes in his own.

Likewise, having the formidable, and seemingly strong priored Warren at the head of CPFA is dangerous. She seems to have strong beliefs and the analytical ability to plow through anyone in her way. A cold-hearted pointy head would make a better referee.

That’s not to say that passion has no place in intellectual discourse, but it is why its important that passions balanced. It doesn’t matter how good your intentions are, confirmation bias and a lack of diversity will leave glaring blind spots.

According to a recent study that analyzed over two billion tweets, it’s not all about having lots of followers. Some of the most influential twitterers have few followers:

“Having a million follows may not be everything in terms of influence,” said Meeyoung Cha, of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Software Systems… In relative terms, she said, one of Twitter’s most influential users turned out to be a librarian who had few followers but a high rate of success at having messages mentioned or forwarded.

This should be a consolation to those twitterers with only a handful few followers.

Matthew Yglesias opines on articles about medical practices from Igor Volsky and Ezra Klein:

This is all bad stuff and not primarily because it “costs money.” Rather, it costs people quality of life. People have better things to do with their time than undergoing painful cancer treatments that they don’t need. Gawande writes of a study “showing that terminally ill cancer patients who were put on a mechanical ventilator, given electrical defibrillation or chest compressions, or admitted, near death, to intensive care had a substantially worse quality of life in their last week than those who received no such interventions” and also “six months after their death, their caregivers were three times as likely to suffer major depression.” I don’t think there’s anyone out there who’s terminally ill and saying to himself “I want to handle this in the way most likely to produced major depression for my loved ones” but that’s what happens and it’s horrible.

The “bad stuff” Yglesias refers to is the extreme treatment given to people who are either of questionable risk, or who are “heading out” anyway, and the extra treatment is not only a…less-than-optimal…use of money, but also destroys quality of life.

Ezra’s story, more-so than Igor’s, is a rather extreme example of using medicine to signal our loyalty to people. Presumably, a medical proxy or power of attorney needs to sign off on these extreme end-of-life treatments. What I find interesting — and something that is absent in Matthew’s analysis — is that this type of behavior carries substantial personal (non-monetary) risk in the form of depression!

On that point, I think Matthew has it exactly backward when he makes the statement that concludes the quote above regarding a terminally ill patient. I don’t think that this is a situation where the receiver of “care” is making a selfish decision regarding their final days. Rather, it is those in charge of the “care” decisions; in an attempt to signal that they do, in fact, care, taking drastic steps that have little or nothing to do with either making someone better off health-wise or marginally improving quality of life.

Robin Hanson has argued that we should cut medicine in half. I tend to agree with that. Though one interesting thing that digging into the end-of-life data may shed some light on: The desire to signal that we care obviously fades the “further” we get from the patient in question. I wonder if there is a demonstrable link between the closeness of the medical proxy and the incidence of extreme, unneeded medicine?

And here’s the kicker: Is improving quality of life a possible argument for “death panels”?

Kevin Drum, who is not a no-growth economist, analyzes what a no-growth economy would look like.

This is….a wee bit rosy. If we all worked two days a week, I suspect the real result would be more time spent playing video games and drinking beer, not a renaissance in the arts and sciences. And more time to look after sick relatives? I’m not sure everyone would consider this a boon.

…and then he aptly notes:

…In other words, not only wouldn’t we get a renaissance in the arts and sciences, we probably couldn’t afford video games or beer either.

This is all very correct. No-growth economics is almost exclusively the intellectual realm of the left. I mean the type of lefties that have no problem with sawdust toilets, grass huts, and foraging. For those of you scratching your head as to how one goes about achieving “no-growth economics” in a world where people have a propensity to discover, adapt, and amplify different methods and tools for achieving ends more efficiently…well, I’m right there with you.

The biggest problem that faces the entire world is a scarcity of wealth, and economic growth is the natural result of cooperation and competition that people engage in to maximize their wealth. What is happening here is that proponents of “no-growth economics” have completely misidentified their intended target, and have thus made themselves a model which is extremely high on idealism, and extremely low on realism.

So if economic growth isn’t the proximate cause of the injustice that leads people to an incoherent economic model, what is?

Our money system.

It is assumed in economics that money is a value-neutral accounting device.* That the rules of the monetary system itself do not shape the kind of transactions that are made, it just makes them easier; and that the type of money we use has no effect on the relationships between the users. I make nearly the exact opposite claim, and that we take this fact for granted in a way that artificially prevents us from meeting needs with unused resources.

Humans have an incredible ability to find ways to waste eachothers’ time put eachother to work. I doubt that anywhere in the world there is a shortage of imagination. So what is the problem? A shortage of money. And why is that? Because of the rules governing how the prevailing monetary systems of the world work.

People who advocate for “no-growth economics” should realize the incoherence of their views, and instead advocate the use of complementary currencies — currencies which operate under different rules — that circulate alongside legal tender.

*I am using the term value-neutral in a different way than economists when they talk about the neutrality or super-neutrality of money.

Soon, we will likely see the worst case scenario come to pass in the name of “preventing climate change”, and that is to have a command-driven regulatory agency dish out quotas and make peripheral tweaks to existing regulations in order to look like they’re doing something productive. It is unlikely that climate legislation will pass the Senate in this Congress or the next…and that is a tragedy.

I place the blame squarely on Republicans; centrist and conservative alike. I tend to think that Democrats gave a lot on this issue…and I grant them that even though their preference for centralized solutions to environmental problems are oftentimes wrong on the merits.

To be sure, cap and trade was not my most preferred solution, which is a carbon tax…which was never even close to the table due to the Republicans’ successful campaign against the word “tax”. A carbon consumption tax would have been the most efficient, least intrusive way in which to deal with whatever specter of environmental degradation exists (even if it’s not climate change, per se, and just happens to be smog). But, cap and trade was a very large step in the direction of markets anyway — and the ACES bill passed the house! I have previously voiced my concern about the (lack of) possible impact that the ACES bill will have, but my problem was not with the premise.

Let’s quickly review two simple definitions of how governments interact with markets:

- Policies that get the government involved in differentiating, selecting, and amplifying business plans.

- Policies that shape the fitness environment, while leaving business plan differentiation to entrepreneurs, and selection and amplification to market mechanisms.

Now, hold constant that this government will act in a way consistent with the fact that they believe that climate change is a serious issue. The most optimal solution is for the government to put a price on carbon (shape the fitness environment) and let businesses and individuals figure out how they will adapt to the new evolutionary landscape. Wait…that’s exactly what ACES did. Sure, there were a giveaways, and it questionable whether the bill would “do anything” to prevent global warming — but those are mostly semantics. The point is, it is consistent with my preferred role for the government.

However, since pricing carbon is not in the cards for this or the next Congress…and given that our government is looking to act against climate change…and given that there are a myriad of very, very inefficient regulations already on the books that fit into the first category of government action, we are all but destined for sub-optimal policy (like regulation by the EPA).

And I blame you, Republicans.

A new paper from the Boston Fed investigates the transfers that occur as a result of credit card interchange fees:

On average, each cash-using household pays $151 to card-using households and each card-using household receives $1,482 from cash users every year. Because credit card spending and rewards are positively correlated with household income, the payment instrument transfer also induces a regressive transfer from low-income to high-income households in general. On average, and after accounting for rewards paid to households by banks, the lowest-income household ($20,000 or less annually) pays $23 and the highest-income household ($150,000 or more annually) receives $756 every year.

I’ve only read the abstract, so I can’t vouch for quality, but the headline numbers are interesting. It’s important to remember that the interchange fees pay for the existence of the entire system, and so there are many benefits that must be weighed against those costs. The availability of short term revolving credit may be much more valuable to low-income households such that the net costs and benefits are not actually regressive.

I’ll get to this graph in a minute

When I was a economics undergrad multinational corporations were the public enemy of choice. We were taught as young defenders of the faith, to look beyond the intuitive connection between profits and evil. We were told that the equilibrium was the result of competing forces and that sometimes what looked like a cause was really a symptom. Sweatshops were a case in point.

Today the villain has a very different face. Its big government and its apparently uncanny ability to screw everything up. If something went wrong government is likely to blame.

Queue the housing crisis.

I watched the housing and financial crisis unfold in real time. I had considerable personal interest in the outcome. It seemed beyond doubt among those biting our nails over whether there would or wouldn’t be a crash, that the key player here was the Collateralized Debt Obligation. It was a newly popular product. It promised fantastic results. It had revolutionized the market and from the very beginning many had complained that it was too good to be true.

From an economic standpoint the argument was a standard one. The modern CDO was a technological innovation. Large scale CDO issuance was impractical before David Li developed a Gaussian Copula model to estimate their performance.

This always happens with new innovations from the Railroads to the Internet. Some nut says that its going to change the world as we know it and some old fogy says its no different than the fax machine. Usually they’re both at least right. We have Googles and we have Webvans and no one knows before hand which will be which.

Yet, and still I didn’t find it surprising when millions poured out to blame the housing crisis on corporate greed. I had been trained to expect it.

What did surprise me is that people wanted to blame it on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? You mean those old stogy has-beens that the CDO was supposed to make obsolete? A 30 year 80-20, that’s for suckers. Those were the days of the 2/28 ARM at 135% LTV. It was truly money for breakfast.

Yet, that’s where the blame went. The government had intervened in the housing market. The housing market had gone bad. Therefore, the government must have screwed up the market. QED.

This theory was pushed by econ-types, business or pro-market pundits who were used to defending corporations. I was sure, however, that eventually their training would kick-in. They would look for auxiliary factors, try to examine competing theories and most importantly check for evidence that would directly contradict that theory. That didn’t happen.

And, that brings me to graph at top. It seems to me that if you believe the American government did something to screw up the American housing market the very first thing you would ask is – what happened in other countries. Its authoritative since government polices are usually defined over government jurisdictions. Its really convenient, as countries usually collect their own data and post it online for you. Its the first place you should look.

A causal glance, however, tells you that there was a bubble all over the world. The US wasn’t even particularly bad and that even the free market wunderkind of Ireland was about to take it in the teeth. As far as I can tell that’s pretty much what happened. This makes the Fannie/Freddie done-it theory seem highly implausible. Even if there are international spillover effects, at a minimum one would expect Fannie and Freddie to have done it most in America. America actually had one of the least – which might have something to do with Fannie and Freddie, but that’s for another day.

My take away isn’t that government is the answer. I’m generally a Hayekian and I see the information problems associated with government as being often insurmountable. No, the take away is that villains aren’t the answer. When you see things going wrong its a mistake to assume that someone made them go wrong. And, its got to make you at least a little suspicious if the someone you suspect was a person you didn’t like to begin with.

Economists like to say that the economy is not a morality play, where the good are rewarded and the evil punished. Its not a Bond film either, where there is a super villain – business or government – behind it all. Its a complex interaction of forces that we can only hope to understand by careful examination. Sometimes the government will screw up. Sometimes the private sector will screw up. Sometimes shit happens. That’s not always emotionally satisfying but it is the nature of the discipline we have chosen.

I will be on vacation for the whole week so my blogging will be light… or at least as light as I can help, since blogging tends to be a compulsion rather than a choice.

When people talk about government intervention as a causal factor in the house price bubble, they’re usually talking about the contentious issue of Fannie/Freddie, the CRA, and other policies associated with encouraging homeownership. Much more important than those factors, whose existence are not necessary conditions for the bubble, may be local regulations that restrict land use. A new paper investigates:

“Using data from 326 US cities, our study examines empirically how residential land use regulation, geographic land constraint and credit expansion are related to the swing of house prices between January 2000 and July 2009… We find that cities that are more regulated or have less developable land experienced greater price gains between January 2000 and June 2006, and greater price declines between June 2006 and July 2009. In addition, the natural and man-made constraints both amplified the responses of house prices to an initial demand shock arising from the mortgage market, turning the shock into a greater price gain and subsequently a greater loss. Finally, over the entire period, cities that had more marginal borrowers before the credit expansion did not experience greater growth in housing prices, indicating that the subprime expansion did not leave a positive legacy on the price front.”

I think convincingly proving this would require some panel data rather than the cross section used by the authors, and potentially some natural experiments. But I am glad to see this being investigated empirically, it strikes me as an important point: some very very common regulations may have serious unintended costs.

Lie to me. I promise I’ll believe. ~Sheryl Crow

Adam gives a rather sophisticated argument against menu labeling that boils down to this: finding out something you’d rather not know makes you worse off.

This presents something of a problem for economics and economists because we typically think of information as determining how closely one’s actions are aligned with one’s preferences. That is, the more you know the more likely you are to get what you want.

Serious analytical problems arise when you have preferences about what you know. That is, when they’re some things that you just don’t want to hear. Yet, this is a deep and undeniable part of being human.

The always entertaining Ricky Gervais made a movie about it called the Invention of Lying. In Gervais’s film no one, until Gervais comes along, ever lies. Yet, as weird as the world in The Invention of Lying is, it doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of how fundamental lying is.

Now let me warn you before I go any further, you are not going to want to hear this. Indeed, that’s my point. I’ll say it anyway because I care much more about the displaying my intellectual prowess than I do about your personal comfort ~ that wasn’t very nice was it?

Lets start with some basics. First off, if social psychology is correct then you are much bigger failure than you realize. In fact, you’ve probably failed at most things. Now, since those things have happened you’ve actually rewritten your preferences to claim that you really didn’t care that much in the first place, the things you succeeded at mattered more, there is a reason for everything, every cloud has a sliver lining, when God closes a door he opens a window, and a whole bunch of other lies.

These lies are almost undeniably helpful because research tells us that the people with the most accurate self-assessments are those that are chronically depressed. That is, the truth hurts – a lot.

But lets not stop there. Perhaps you have children or perhaps you’re planning to. Our best available research tells us that they are probably on net going to make you less happy. You know the only people who are happy to hear that – the middle aged and childless. Almost, everyone else is kind of pissed and goes through intellectual gymnastics to try to deny it. It doesn’t feel great to think that the light of your life is when all is said and done more of a pain in the ass.

It gets worse though. Because as a parent you probably don’t even care that much about your children. Indeed, once your children’s abstract reasoning starts to mature, around 14, they will be sure to tell you exactly how little you care about them or what’s important to them. You know what? They’re right. You don’t. You don’t because you’re not hardwired to care about them. You are hardwired to care about their genes.

Caring about their genes means first and foremost making sure they survive long enough to reproduce with an adequate mate and adequate resources to give you what you really want – healthy grandkids. Getting there might involve a lot of pain for your kids and maybe on some level that irks you, but likely not enough to keep you from driving down their utility in an attempt to drive up yours. If you’re really good at it they will become stunning successes with beautiful successful spouses and lots of wonderful healthy grandchildren. And, there is a good chance they will never forgive you. Nor, should they.

We haven’t even started in on how tribalistic, ethno-centrist and racist you are. Here is a good place to get started on that. Basically, you suck and we’ve got the data to prove it.

All that information is like a breath of fresh air isn’t it?

After you’re done ruminating on the ways in which you’ve been a bastard – e.g. if all my friends have credible stories showing that everyone else is an asshole driver and I’m someone then . . . – perhaps you’d like to stop off for a quick bit to eat. You’re a little overweight sure. I mean you’re an American so chances are. This, however, is a moment to take a break before you face that failure that is your life and trust me it is a failure.

“That’ll be seven ninety-five” the cashier says, “oh and 900 calories (that you definitely could go with out)” I added that last part but you know that you heard her say that in your head. Just one more reminder that you suck. But, hey if this menu labeling works then you could have three more extra years to ruminate on all the things that you wished you’d done but you and I both know you’re too lazy and/or chickenshit to ever do.

Cheers.

From James Poulos, in response to Conor Friedersdorf:

The only strip club that would be like the Cordoba House would be possibly the most wondrous strip club in the history of Man: a thirteen-story, sex-themed community center, dedicated to the practice and promotion of erotic dancing, constructed as a soberminded matter of high-stakes public relations in direct response and in closest attainable proximity to the scarred footprint of a collapsed living landmark destroyed on national television by a murderous, fanatical band of fundamentalist strippers, naughty girls in the grip of a kamikaze certainty that the truth about erotic dance is that innocent Americans, as many as you can kill, need to die a fiery, hideous death.

James, I would very much like to co-write this movie with you.

Jodi Beggs, aka Economists Do It With Models, argues that paternalism need not be justified by assuming irrational agents, but can simply be an efficient response to an informational problem:

Any Economics 101 course will tell you that a required condition for markets to be efficient (read, value-maximizing for society) is that consumers have full information about the products they are considering consuming. In this way, the calorie-labeling legislation is helping to push the fast food market in the direction of efficiency as much as anything else. What’s so behavioral-y about that?

One counter to this is that markets should be supplying the amount of information that consumers prefer, and that the reason we don’t observe a lot of menu labeling and other information from restaurants is because consumers don’t want to know. Of course, you could argue that they don’t want to know only because of what they don’t know…Wait, what?

Ok, bare with me. Pretend I had a sealed envelope that contained a letter from someone telling you telling you exactly why they hate you. But say you believe that everyone who you care about doesn’t hate you, therefore you assume it’s from someone you don’t care about, and since you don’t want the annoyance of reading hate mail from someone you don’t care about, you choose not to open the letter. But, say that letter is from your wife, who secretly hates you. Well you would want to know why your wife hates you, but since you believe your wife can’t possibly hate you, you won’t get information you want. Basically what I’m saying is that your current information set determines your demand for information.

So what does this have to do with menu labeling regulations? If we assume markets are working, then the level of information we observe is the amount demanded by consumers, which efficient. In this case menu labeling laws would make people worse off by giving them information they don’t want. That is unless the amount of information they are demanding is based on their assumption that restaurant food is kind of unhealthy, but not as unhealthy as it really is. If they had any idea how bad it was, they would want to know. In this case menu labeling laws could make people better off.

Determining the source of the lack of information is critical to knowing whether menu laws are efficient or not. This is especially important because the amount of information can affect demand, which contra Jodi, can change the choice set. She writes:

…the consumer has exactly the same set of choices available to her regardless of whether calorie counts are on the menus or not. Because of this feature, it’s hard to argue that this sort of legislation is significantly bad for anyone- here, the worst-case scenario is that some people keep eating unhealthy food but are no longer blissfully ignorant and instead feel guilty.

But what could happen is that when people are no longer able to be blissfully ignorant, which they prefer, they consume a healthier but lower utility set of products. This in turn could change restaurant supply decisions, which would mean a different choice set.

So what is it: is our demand for ignorance efficient, or is our ignorance causing us to demand an inefficient amount of ignorance?

Via Andrew Sullivan Lane Kentworthy charts US income disparity

Its impressive that the income for the Top 1% races off while the income for the middle and lower class is squished towards the bottom.

I was concerned, however, that this chart might be somewhat misleading because even if the various income classes had the same growth rate – not suggesting they did, just saying – the increases for the Top 1% would dwarf everyone else, since they started from a higher baseline.

I tried plotting the income growth as common logs

A similar though, perhaps, less shocking looking story. There is growth, albeit mild in the middle and lower classes, and stronger more robust growth among the Top 1%.

If your used to common logs then you can see that the Top 1% moved from being about an order of magnitude above the middle class to about one and half orders. Or in other words from 10 times greater to 30 times greater.

However, you still don’t get a good sense of the trajectory. For that I plotted an index scale where 100 is income in 1979.

Here we can see that the Top 1% has more than triple its income with fairly steady growth since 1980. The middle and lower classes have seen only about a 15% increase in real income with all of those gains coming after the early 90s.

What’s even more interesting to me is that the gains to the Top 1% seem to be steady and at first glance trend reverting. That is, there appears to be a consistent underlying rate of growth ever since 1980, with income rising above trend during booms and falling below during recessions.

Plotting the trend line reveals that the Top 1% is seeing its income grow at roughly 4.2% per year in real terms.

This is significantly faster than real growth of US GDP.

My first question then is whether this is increasing take of GDP is because of the Top 1% position as high end wage earner or owners of capital. The standard story has largely been that increases in technology has expanded gains to the most educated, those working in high tech fields.

Looking at the sources of income for the Top 1% its not so clear.

There is a lot of fluctuation but I don’t see anything to suggest that the income growth of the Top 1% is being driven by their position as high-end, highly technical wage earners (MDs, Executives, Software Architects)

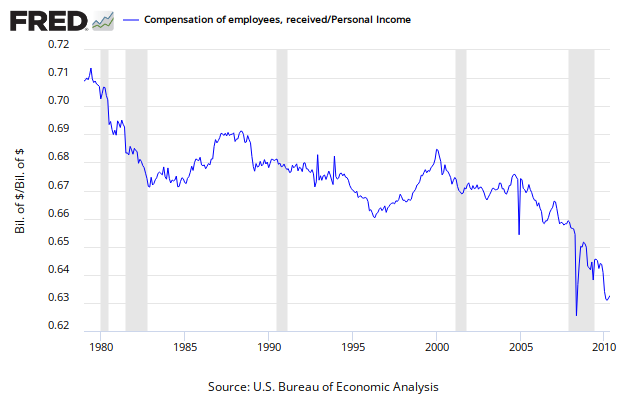

And at least in the aggregate, wage earnings seem to be becoming less important. The chart below show employee compensation as a fraction of personal income.

More analysis to come.

From Kevin Drum:

The Republican Party has long been pro-business, not pro-free-market, and the same is largely true for the Democratic Party these days. And while liberals are unlikely to ever team up with conservatives on a pro-business agenda, which generally just means handing out goodies to favored patrons, I think a pretty sizeable number would be willing to team up on some aspects of a pro-market agenda if that were actually on the table. There would still be plenty of areas of disagreement (we liberals remain sort of attached to the idea of helping the poor and the middle class), but some areas of constructive correspondence as well. So if there are some non-wild-eyed pro-market conservatives still left alive out there, let’s hear your agenda. It might be interesting.

First of all, I’d like to say that the dichotomy between markets and “helping the poor and middle class” is a false one. Highly-functioning markets are almost assuredly welfare-enhancing to the poor and middle class. Indeed, without the wealth generated by the market selection mechanism, it’s hard to see how you would go about helping those people in the first place…but that’s a tiny nit to pick, on to the meat!

Recently, a few leftist-liberals have come out in support of a progressive consumption tax taking the place of the current income tax regime. Of course, I’m fully behind this idea, and I think that this is certainly a pro-market. Combine this with a progressive payroll tax, and some special taxes that address certain externalities (no, smoking and being fat are not externalities), and you could raise just as much, if not more revenue from relatively low tax levels. This is a huge boost to supply-side incentives. This means removing capital gains taxes, as well…

After the tax structure, the other big elephant in the room is social security. Leftists get very bent out of shape when conservatives start talking about social security, and probably rightfully so — pure privatization is obviously against their feeling of “social good” — but it is also a red herring. The current setup of social security is a head-scratcher…but it doesn’t need to be this way. The government could easily subsidize (forced) private retirement accounts up to a certain level of income yearly, indexed to inflation. Beyond that, have the default selection be risk-free TIPS or bonds, and let people dial up the risk in their accounts as they see fit. 99.99% of people would stick with the default option, and the government shouldn’t subsidize the losses of the .01% that decide to gamble.

Here is a piece that I have written on health care policy. As a preview: I don’t buy the “moral hazard/adverse selection” chants. If health insurance operated as insurance, it wouldn’t be an issue that companies couldn’t deal with actuarially. The government could then lightly subsidize whatever it saw fit, and we could get a higher level of equity and efficiency.

On general regulation, to start out with a radical proposal that is right at home with market-friendly libertarians, the FCC would have to go carte blanc. I’d, of course, enjoy seeing other agencies suffer the same fate, but I mentioned the FCC because I don’t think it’s very controversial with leftist-liberals that understand the issue. Otherwise, just generally adopting a stance of regulation as structuring incentives instead of commanding a market…which I think would be a radical change from the current regulatory landscape — especially in health and education policy.

What we need to understand is that markets serve as a selection and amplification mechanism, and nothing more. The role of the government is to shape fitness function. We should distinguish between two types of government action:

- Policies that get the government involved in differentiating, selecting, and amplifying business plans.

- Policies that shape the fitness environment, while leaving business plan differentiation to entrepreneurs, and selection and amplification to market mechanisms.

Our current incarnation of government is blithely obsessed with the first class of action, when (in my opinion) the optimal role of the state is in the second class. The economic role of the state is to create an institutional framework that fosters the evolution of the marketplace, strikes a balance between cooperation and competition, and shapes fitness function in a way that fosters “societal good”. Of course, the notion of “societal good” is vague and diffuse, but just because the meaning changes, doesn’t mean that the mechanisms by which government promotes them should change — they should still stick with the second class of action.

Do those things sound like something my leftist-liberal friends could sign onto?

Since Tim Geithner won’t, I want to try and provide a case against Elizabeth Warren as head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. By no means am I an expert on her record, nor have I followed her every word, so don’t take this as the final word on her… not like you would though. And of course, depending on your positions on these issues, this may well serve as a case for Elizabeth Warren.

I should start by saying that in theory, and maybe in reality, I think the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is a good idea. Obama’s high-level description is certainly something I can sign off on:

He said the new agency would promote “clear and concise information” for consumers to make financial decisions, crack down on abusive and deceptive practices and rein in unscrupulous credit card issuers and student loan companies.

My concern is that the agency will go for restrictions that liberals tend to like but that limit credit for those who need it most, like usury laws. This fear seems like a good reason to side with Tim Geithner in (supposedly) opposing Elizabeth Warren as head of the agency. I think a good test as to whether you should support Warren is how you feel about payday lending. If you’re the type of person who thinks that interest rates of 200% are crazy and shouldn’t be permitted, then you probably will like Warren as head of CFPB. However, if you’re the type of person who thinks that payday lending makes people better off, then you probably don’t want Warren as head of CFPB.

A good place to look to see what kind of agenda she would have as head of the agency is articles and papers in where she argued for the existence of such a regulator. In both places I found her praise of usury laws troubling. These laws, which limit the maximum interest rate a bank can charge, were on the books in 36 states in the late 70s. Some were high enough to be effectively non-binding for 90% of lending, like Georgia whose rate was 60%. Others, like Arkansas whose rate was capped at 5% above the Fed discount rate, were low enough to limit the usage of credit cards and other consumer loans. Warren praises these laws and laments the 1979 supreme court decision that effectively nullified them.

One place these types of interest rate caps could be particularly harmful is payday lending. Warren praises legislators for banning rates above 36% for military families. But if you believe the empirical evidence which shows that access to 200% APR payday loans actually make borrowers better off, then a cap at 36% is a bad idea.

Another bad indicator is how she broadly paints the “problem” that this new regulator is addressing:

Americans are choking on debt. One in four families say they are worried about how they will pay their credit card bills this month. Nearly half of all credit card holders missed at least one payment last year,2 and an additional 2.1 million families missed one or more mortgage payments. In 2006, 1.2 million families lost their homes in foreclosure,4 and an estimated 2 million more families were headed into mortgage foreclosure by 2009. The net effect of subprime mortgage lending is that one million fewer families now own homes than did a decade ago.

There’s nothing wrong with setting the stage for her report by arguing that America has a debt problem, but if she sees CFPB as something that could address these issues then that is problematic. Informational problems and tricky lenders are not the lead cause of these problems, and to try and fix them via those levers would require draconian restrictions.

A final problem with Warren is shown by Megan McArdle’s criticism of her misleading bankruptcy paper. Can Warren be trusted with statistics? I found myself reading her more skeptically than I normally would, and I think that’s justified. She may have lot’s of credibility with the left, but this paper surely hurts her credibility with everyone else.

Overall, I think Warren’s case for clearer disclosure in financial instruments is a good one. For instance, I can sign off on most of these things she calls for the consumer protection agency to do:

It would also promote such market-enhancing practices as a simple, easy-to-read paragraph that explains all interest charges; clear explanations of when fees will be imposed; a requirement that the terms of a credit card remain the same until the card expires; no marketing targeted at college students or people under age 21; and a statement showing how long it will take to pay off the balance, as well as how much interest will be paid if the customer makes the minimum monthly payments on the outstanding balance on a credit card.

But I do worry that Warren and an agency staffed with like-minded individuals would be overzealous and over-restrictive in regulating credit. Unlike other commentators, I see no problem with an agency staffed by grey-beards and stuffy academics.

When I speak to public officials these days I find myself trying to comfort them with the knowledge that the economy is much better than the job market and its the economy, not the job market that forms the tax base.

I show them this chart

to illustrate that even though we aren’t employing that many more people, each person we do employ is making more stuff. Its hard to understand why that should suddenly be the case but this NYT article on Delta makes it clear

“The real engine behind the recovery in the second quarter has been capacity cuts,” said Hunter Keay, an airline analyst at Stifel, Nicolaus & Company.

Like other airlines, Delta has been cutting the number of planes in its fleet to adapt to the drop in passenger demand, which was especially marked last year. The company’s capacity — or the number of seats it offers — fell 0.6 percent in the last quarter. It has 958 planes, 59 fewer than in the same period last year.

Deep consolidation has meant fewer flights and more passengers per flight even as total number of passengers falls. The net result is a much more positive cash flow for the airlines and other businesses

The important thing to remember is that

- Corporate Profits are a tax base.

- Corporate Profits produce a higher average yield than personal income taxes.

Thus from a revenue point of view you are better off hearing that the recovery is a productivity lead one with enormous increases in corporate profits. Though, from expenditure side there is obviously much more strain on public services when unemployment is high.

An important research project remains: what is the extent to which policy makers inside of government internalize the structure of the recovery which would be best at producing revenue. For example, a highly progressive tax during a period in which all the gains in income went to the wealthiest one percent would seem to please no political party but it would undoubtedly produce one of the best revenue pictures.

When I read FiveThirtyEight’s tweet on the weird pattern in searches for racism

fivethirtyeight: Google search traffic on the term ‘racism’ is weirdly cyclical. http://bit.ly/aTdklZ

I immediately saw a seasonal pattern familiar to economists

Searches crashed during the winter and summer. Just like employment:

Could it be that people were most interested in racism when they were hiring new employees?

Then I noticed that unlike employment the biggest crash is in the middle of the year, rather than the beginning. The aha made me smile.

The summer layoff of teachers isn’t nearly as large as the after Christmas layoff of retail employees. However, summer vacation is longer for students than winter vacation. It seems racism – as search term at least – is most prevalent in modern American minds when they are learning about it in school.

A new NBER paper argues that food stamps lead people to work less, especially single family parents:

Labor supply theory makes strong predictions about how the introduction of a social welfare program impacts work effort…. We use the cross-county introduction of the program in the 1960s and 1970s to estimate the impact of the program on the extensive and intensive margins of labor supply, earnings, and family cash income. Consistent with theory, we find modest reductions in employment and hours worked when food stamps are introduced. The results are larger for single-parent families.

This is not to say by any means that food stamps are not still a desirable program, but it is always worth thinking about how you can improve or replace existing welfare programs to better align incentives. This is a reminder that food stamps are not without their potential problems.

Of course, one could see single parents being able to spend more time with their kids as a benefit of this, in fact one might see positive impacts on grades and other outcomes via this mechanism. In either case, it’s important to know that food stamps affect work incentives.

Palin leads GOP candidates in favorability rating both among Republicans

and the Nation as a whole

Though of course her net numbers are the highest of all candidates with republicans +56 and the lowest of all candidates with the general public –3.

Daniel Indiviglio at the Atlantic has another piece on how credit is bad for poor people. Like Daniel’s previous writing on credit and the poor, his reasoning amounts to partial partial equilibrium analysis that misses the big picture and really doesn’t capture the effects of credit on the poor.

One way to clarify the various effects he introduces is to think of them in terms of labor supply curves. First, he argues that credit makes people feel richer, and so decreases wages:

Credit pacifies those with lower incomes to make them feel like they’re better off than they actually are. If you can use a credit card to buy an iPad or new shoes, then you are more satisfied than you would be based on your income alone… The more content you are, the less need you’ll feel to try to increase your income.

So credit makes people feel wealthier, and because leisure is normal good that you consume more of when you’re wealthier, people want to consume more leisure. Therefore the labor supply curve shifts left as people choose leisure over work, and thus wages go up. That part is missing from Daniel’s story. Importantly, it’s not obvious that income goes down in this scenario; it depends on the slope of the labor demand curve.

Ok, so maybe that’s the wrong way to frame it, and credit simply works as an income multiplier instead as a wealth effect. This means individuals get $1.2 worth of consumption from every $1 of income, which increases the returns to income. But this would increase the value of work relative to leisure, which would shift labor supply right, which would decrease wages but increase hours worked. Again, the effect on income depends on the labor demand curve.

So from the start, the effect on income are unclear and depends on the slope of the labor demand curve and the relative sizes of the wealth and income effects. But then Daniel makes the analysis even less clear by undoing the effects he just established:

The poorer you are, the more expensive your credit, but the more credit you’ll feel like you need…And they’re paying relatively high interest rates, which further eats into their relatively lower income, reducing their wealth potential.

So he just told us that credit was increasing peoples perceived wealth and income, but now he’s saying it’s lowering their actual wealth and income. Are people completely unaware of this? Over their entire life that is a highly unreasonable assumption. In fact, most people surely understand from the get-go that borrowing money is not magically making them richer, and that it must be paid for in the long-run. I sincerely hope Daniel isn’t going to argue that most borrowers think they won’t have to pay it back.

So people are choosing to consume more now rather than later, and while ability to smooth consumption should increase their utility, it is far from clear using just the effects that Daniel has laid out whether it increases or decreases their lifetime income and wealth. But when you include other effects, like the increased ability to borrow and invest in positive NPV investments like, say, a college education, it becomes obvious how credit could increase lifetime wealth and income of poor people. Wealthy people don’t need to borrow to make positive NPV investments like that, but poor people do. So the benefits disproportionally benefit poor people.

As I’ve previously written, more credit not only increases investment in college, but also high school and grade school. Given the importance of credit in allowing poor people to make important human capital investments that increase lifetime wealth, income, and well-being, Daniel is going to have to work a lot harder to make a convincing case that credit is bad for poor people. His partial partial equilibrium analysis is not even close.

[Update: broken link fixed]

The brightest economic story in the world these days is that China’s wages are rising so fast that low-end manufacturing is beginning to shift into other countries lower on the development ladder. A beautiful illustration comes from today’s NYT in an article on how jobs are shifting from China to Bangladesh. This is the progress of globalization that critics scoffed at:

As costs have risen in China, long the world’s shop floor, it is slowly losing work to countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia — at least for cheaper, labor-intensive goods like casual clothes, toys and simple electronics that do not necessarily require literate workers and can tolerate unreliable transportation systems and electrical grids.

Li & Fung, a Hong Kong company that handles sourcing and apparel manufacturing for companies like Wal-Mart and Liz Claiborne, reported that its production in Bangladesh jumped 20 percent last year, while China, its biggest supplier, slid 5 percent.

Will proponents of protectionism for American manufacturing jobs against China agree that China should engage in more protectionism to protect its manufacturing jobs from Bangledesh? Clearly, they are at risk:

Among developing countries, Bangladesh is the third-biggest exporter of clothing after mainland China, which exported $120 billion in 2008, and Turkey, a distant No. 2, according to the World Trade Organization.

And with nearly 70 million people of working age, Bangladesh could probably absorb many more of China’s 20 million garment industry jobs.

I would suspect that American protectionists can see that the shift of low-end manufacturing from China to Bangladash is a good thing, as Bangladesh is lower on the development ladder and harming the worse off Bangladeshi workers to protect the better off Chinese workers would be wrong. They probably also recognize that this shift represents the best hope for a country like Bangladesh to move up the development ladder, and using protectionism to get in the way of that in order to preserve Chinese jobs would also be wrong. Why can’t they see the same is true of American protectionism as well?

Subbing for Andrew Sullivan, David Frum rehashes the lump of labor fallacy

But here’s a crucial fact that Brookings omits: that 125,000 per month increase in the US labor force is not a law of nature. In fact, during the Bush years, more than half the growth in the US labor force was due to the arrival of immigrant labor.

Immigrants now make up some 15% of the US labor force. They are concentrated in the less skilled portion of the labor force and in industries hardest hit, especially construction.

If immigration levels were curtailed, the job gap would be a lot smaller. And if illegal immigrants returned home, rather than being put on a “path to citizenship,” the problem of putting the unemployed back to work would be smaller and easier.

The US population and thus the number of job seekers has grown fairly remarkably over the last 200 years. Why is it that unemployment hasn’t grown steadily as well?

Because every worker is also a consumer. When you send a immigrant worker packing you are sending his consumption packing with him. For those who have trouble with the abstract interwovenness of the economy think about it this way: Is the one thing our economy really needs right now fewer residents and thus less demand for housing?

If anything we have a construction industry which is predicated on a large and growing population. Perhaps faster growing than we can maintain, but in any case, slowing down growth is not likely to improve matters.

Ryan Avent has made some important points about the structural problems in the labor force. And, this is something that I hope I’ll get a chance to address directly.

But, I will reiterate, we didn’t get smacked with some grand structural calamity in the last 24 months. We got smacked with a huge increase in liquidity demand and federal funds rate stuck a zero.

Innovative monetary policy is the solution1. Not the 2010 Smoot-Hawley labor trade restriction act.

(1) I am not rejecting fiscal policy as fiscal and monetary policy become mixed at the Zero Lower Bound.

Seems that Paul Krugman no longer “believes in” liquidity traps:

The passivity of the Bank of Japan offers an object lesson. The BOJ is now under political pressure? Why? Because it still sees no reason to act after fifteen years of deflation.

He is certainly in good company ;].

One of the biggest problems that has plagued economics has been its reliance on a theory that lies at the very core — that of human behavior. As you may surmise, macroeconomic phenomena is the emergent result of micro-interactions between markets, businesses, and ultimately, people. By now, you may have guessed that I’m talking about perfect rationality.

Economists have relied on perfect rationality — and it’s permutation: bounded rationality — since as long as there have been models of the macroeconomy. The reason for that some assumption of forward-looking rationality is required to create a computationally efficient equilibrium model. Of course, even a ten-year old child could demolish the theory of perfect rationality. Here, Arnold Kling makes the case against (popular) modelling of rationality:

I think that my least favorite Sumnerian proposition is that the Fed can affect the economy by announcing a long-term target for a nominal variable. I think that in order for this to work, you have to assume that people are forward-looking and focused on future monetary policy. On the other hand, his mechanism by which monetary policy works is the conventional story in which nominal wages are sticky, so that with higher aggregate demand you get lower real wages and more real output. But for nominal wages to be sticky, workers cannot be forward-looking and focused on monetary policy. So, on the one hand, for targets to matter, people have to be forward-looking. On the other hand, for monetary policy to matter, people cannot be forward-looking. I cannot past what I see as a basic contradiction. For what it’s worth, in case you cannot tell already, I do not think that people are forward-looking. I think that they are habit-driven and backward-looking.

Because I believe that people are habit-driven and backward-looking, I think it is possible for real wages to fluctuate. However, I do not think that real wage movements have been very important in post-war economic fluctuations.

This is important, because Kling is right. Very few people are forward-looking in a way that makes a lot of difference in the macroeconomy. I’ll return to this later. However, this type of theory of human behavior lies at the core of complexity economics. The CE theory states that humans think inductively, have highly-incomplete information, are subject to numerous errors and biases, learn to adapt over time using trial-and-error “deductive tinkering”, and are highly heterogeneous in preferences, and only work to “satisfice” a vague notion of utility.

In reality, many types of economic problems turn out to have no perfectly rational solution at all — in theory or practice. Take the Bar Problem:

A popular bar offers live music on Thursday nights. It is not a large bar, however, so you have a comfortable and pleasant evening if no more than sixty people show up. More than that, and it becomes crowded and uncomfortable. You decide that you wish to go, only if there are fewer than sixty people planning on attending, otherwise you will stay home. Obviously you have no way of communicating with the large mass of potential patrons, and let’s assume that the bar has no interest in giving you an (accurate) average turnout. All potential patrons make their own decision in the same way. Do you go or stay home? How do you decide?

As with many things in life, there is no rational solution. There is an infinite circularity problem — what you do depends on what you expect me to do, which in turn depends on what I expect to you to do, and so on. So how do people make their decisions? Well, they look at their past visits to the bar, try to identify a pattern, and then make their choice. There is a strong path-dependency, where positive and negative experiences are reinforced (and result in a greater probability that you will or will not go to the bar, respectively).

Brian Arthur has run computer simulations* of agents following such “rules of thumb” and has found that the bar never settles into an equilibrium.

Cognitive science has gone a long way in showing that human beings are capable of incredible feats of information processing, but do so in a way that is entirely different than the picture painted by rationality in economic models. Humans are bad at math, but excellent at storying-telling and listening. As it turns out, storytelling and listening are vital to the way we process information: through induction; or reasoning by pattern recognition. Anyone who has watched an episode of CSI or Law and Order has born witness to the depth of skill humans possess to work their way through patterns, remember long-term trends, and adjust behavior quickly to adapt to newly arising informational patterns. There are two ways humans excel at performing these activities:

- Relating new experiences to old patterns through metaphors and analogies. Take a moment to listen to people on the news talk, you’ll hear things like “this is the worst recession since the Great Depression“, or “this reminds me of Seattle”, etc. What is the internet like? Well, there are numerous books trying to define it as “like” or “unlike” television, radio, magazines, etc. Just go back and read about the Dave Wiegel fiasco…

- Second, we are excellent pattern completers. We fill in missing information using a mix between induction (past experience) and deduction (crude probability) to arrive at a conclusions that are “correct enough” (ostensibly to keep us alive!). This was obviously an essential skill in our ancestral environment.

Just take a look at the gambler’s fallacy, or sports “hot streaks”, or people looking at clouds…we see patterns literally everywhere! Of course, this behavior is also has bearing on how power law distributions are formed in economies (and in nature, which is also “satisficing”).

Now, why am I still an AS/AD guy after everything? Well, because it is important to note that there are people who spend a lot of time trying to compute deductively to bring supply and demand in line. In fact, it is likely that supply would never meet demand in the macroeconomy if not for these agents. In financial markets, these “people” are, of course, referred to as “market makers“…but of course virtually all markets are (perhaps unconsciously?) designed around the expectation of disequilibrium…we have inventories, order backlogs, slack production capacity, middlemen, and supply chains to smooth out transactions. Car dealerships, for example, do not have empty lots — but they do have some cars that you will need to be put on a waiting list for….

The interaction of this “market making” activity in the greater economy is what, I believe, keeps some of the more sensible forward-looking theories of money afloat.

*Arthur (1994b)

Amidst all of the talk about crazy aerial acrobatics that the Fed could do to boost aggregate demand through highly unconventional policymaking, I wanted to bring attention to my own crazy idea:

- A participating businesses secure a invoice insurance up to a predetermined amount, based on creditworthiness and claims on third parties.

- Business A then opens a checking account with the clearing network (CCC) and electronically exchanges the invoice for clearing funds, and pays it’s supplier (business B) immediately through the CCC.

- Business B then only needs to open an account with the CCC. Then it faces two options; cash the claim in for legal tender (at the cost of paying the interest for the outstanding period, and banking fees), or pay it’s own suppliers which the obtained clearing funds (zero cost).

- At the time of maturity, the network gets paid the amount of the invoice in legal tender, either by business A, or the insurance company (in the event of bankruptcy). Whoever owns the claim at that point can then cash their CCC claim for legal tender without incurring interest costs.

Alternative currency systems not only provide businesses with liquidity in monetary disequilibrium and can provide a smooth transition between use in good and bad times, they also increase the velocity of legal tender within economies.

Despite my dismay at the Feds unwillingness to take dramatic action I really do think we have a variety of quasi-conventional means at our disposable to create monetary stimulus. As always an explicit price level target would be a good start.

However, it doesn’t end there. The Fed can buy up all sorts of government debt, including the debts of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. And, and in the end there is always the helicopter option – that is just tossing money from a helicopter.

Paul Krugman worries that the helicopter option wouldn’t be strictly “legal” as they say. The Fed has no authority to just hand out cash. Matt Yglesias says the Fed can just issue $1000 loans with a pair of socks as collateral. If people are “happen” to default on the loan the Fed will just refuse to return their socks.

However, its really even easier than that.

The Fed can purchase bonds backed by consumer credit. In the same way that Wall Street takes your mortgage and bundles it into a set of bonds, firms also take your credit card payments and bundle them into bonds.

The Fed can buy those bonds and to my knowledge there is no limit on the price they can pay. Bond prices are inversely related to interest rates. So, if the Fed pays a high enough price for the bonds, the effective interest rate would be negative.

This in turn would mean that the consumers would make money simply by borrowing money.

I don’t envision lots of credit card offers that say “–3% APR” However, I can imagine offers that say “0% APR for life on new purchases and 10% cash back”

For super nerds, notice that such a temporary credit facility would create de facto inflation. That is, if you get 10% back for buying something today. Then in effect it will be 10% more expensive tomorrow. This will balance against the actual deflation that is building.

I, personally, learned next to nothing about the monetary policy stance of the nominees to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors at today’s Senate hearing. Janet Yellen, Peter Diamond, and Sarah Bloom-Raskin all seemingly showed up to the wrong hearing! The hearing that I saw was almost solely about financial regulation.

This is what I tweeted to Chris Dodd:

@chrisdodd PLEASE ask them: “Do you believe that the Fed can stimulate aggregate demand at the zero lower bound?” #frbhearing

Here is the closest I have to go on from Janet Yellen:

July 1 (Bloomberg) — Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President Janet Yellen said the prospect that policy makers will leave the benchmark U.S. interest rate near zero for the next several years is “not outside the realm of possibility.”

“We have a very serious recession, we have a 9.4 percent unemployment rate,” and inflation possibly falling further below the Fed’s preferred level, she told reporters yesterday after a speech in San Francisco. Given the recession’s severity, “we should want to do more. If we were not at zero, we would be lowering the funds rate.”

These are not very inspiring statements.

[H/T to an old Scott Sumner post]

In a debate on free trade with Ryan Avent, Tim Duy brings us a quote from Alan Blinder, who provides a scary number:

In some recent research, I estimated that 30 million to 40 million U.S. jobs are potentially offshorable. These include scientists, mathematicians and editors on the high end and telephone operators, clerks and typists on the low end. Obviously, not all of these jobs are going to India, China or elsewhere. But many will.

Duy takes the 40 million estimate at face value and concludes that America may be on the verge of having no competitive advantage. This 40 million number is a few years old, and if you read the paper Blinder wrote rather than the op-ed Duy linked to you’ll get a much different sense of the severity of this number. There you will see that Blinder really means it when he says in his op-ed that 40 million is just the number of potentially offshoreable jobs. There’s no quantitative or empirical measure showing these jobs are “very vulnerable” as Duy says.

As a little antidote to all of this doom and gloom it’s worth taking a closer look at one of these “very vulnerable jobs”. The quintessential offshored job is customer service. Most of this takes place over the phone, and if you believe scare mongers, most of these jobs will be done in India in the near future, in fact most have probably been offshored already. Blinder, for example, says “the jobs of call center operators are clearly at risk”. But according to the BLS, there are currently 2.3 million customer service representatives in the U.S. in 2008, most of which work in call centers. In addition, the number of these jobs is expected to grow faster than average, or 18 percent from 2008 to 2018.

Here is how the BLS describes the prospects for this job:

“Prospects for obtaining a job in this field are expected to be good, with more job openings than jobseekers. In particular, bilingual jobseekers should enjoy excellent opportunities. Rapid job growth, coupled with a large number of workers who leave the occupation each year, should make finding a job as a customer service representative relatively easy.”

This is at odds with the doom and gloom of Blinder and Duy. My guess is if you were to take a closer look at any particular industry that goes into Blinder’s 40 million number and you will find that the “very vulnerable” is not an apt description of the majority, or even many, of the existing jobs.

Much wailing and gnashing of teeth about the blogosphere over the Fed’s June minutes. Paul Krugman says it succinctly:

I have no idea why Fed presidents expect core inflation to rise over the next two years. Historically, high unemployment has been associated with falling, not rising inflation. In fact, my bet is that we will be near or into deflation by 2012.

But even given the Fed’s own projections, it’s not doing its job, it’s missing its targets. Yet it apparently sees no need to act.

Well, Paul unless I am misremembering how the Fed constructs these forecasts its actually worse than that. These forecasts are generated assuming optimal monetary policy. So the Fed is saying even if it acts in the best possible way it still expects to miss it targets well into 2012.

That’s ignoring the fact that its 2010 – to late to influence – inflation numbers still look a bit rosy to me.

The Fed is literally planning to fail. This is not good. Not good at all.

So I really don’t want this to turn into an argument about the evils of genocide, slavery, Jim Crow, apartheid, imperialism or what have you.

I just think there is a compelling narrative developing here that has nothing to do with demonizing any particular group. I have little doubt that if the positions of various races/ethnicities were swapped the result would be the same.

All that having been said, it looks to me that people aren’t opposed to spreading the wealth around so much as they are opposed to spreading it to Brown and Black people.

In a somewhat controversial paper Alesiana, Glaeser and Sacardote suggest that ethnic differences explain generosity of the welfare state around the world. In the US, in particular the greater the percentage of black residents the weaker the less distribution available though welfare.

Kevin Drum points today to the common observation that American’s want to cut spending, but they see the most gains from cutting Foreign Aid.

It also worth noting that Defense is least popular when its viewed as Nation Building. When its Nation Destroying as in the beginning days of the Iraq War its pretty popular. However, when we switch to nation building popularity collapses. Still not to the level of actually aiding other nations, but still.

One interpretation is that American voters are confused, irrational one might even say. They don’t know what they want.

Another hypothesis, however, might be that they know exactly what they want but are unable or unwilling to articulate it. They want to avoid giving away their hard earned money to people who don’t look like them.

Nor, should we find this surprising. The evolutionary psychologist in me would expect just that. After all, we don’t really, really care about other people. We care about other people’s genes. And, we care about other people’s genes because they likely share some of those genes with us. That is, of course unless they look radically different than us, in which case they probably share few.

Indeed, I would argue, and this probably deserves in own post, that cosmopolitan who want to save the world and give to poor people of all colors want to do so precisely because on an instinctual level they are not really sure what they themselves look like.

Without an abundance of mirrors in the evolutionary environment we probably picked up our cues on what we looked like by examining what our friends and family looked like. Anyone who was different from them was likely different from us.

But, if you grow up in a completely diverse environment then you have no idea what you look like, at least your base instincts don’t. And, so you naively assume that the Third World Kid or Ghetto Youth is just as related to you as everyone else. Hence, your willingness to give.

Now, if someone would be so kind as to supply me with 1000 infants of varying races and $100 Million dollars, I will be happy to test this out.

So, that not how they put it but this chart is pretty damning, despite the amazing claims made in the captions.

So look there were various dips in revenue sense 1965, corresponding mostly to recessions.

Indeed, one of the interesting points, made on the slide which proceeds the now infamous one is that you can make a much stronger case for the Reagan tax cuts which resulted in a revenue dip but it looks like we had almost a return to trend. Not quite but close.

However, one of these dips is not like the others? Which is it? I’ll give you a hint, it is associated with the mildest recession in the post-war period. It’s also associated with the Bush tax cuts.

See how unlike the past there is not even a hint of a return to trend?

The way I see the debate about market confidence and economic policy, there are two things to worry about:

- There are the real fundamentals, e.g. economic growth, future government revenues and expenses, etc.

- There is market confidence.