You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘housing’ tag.

Economists like to say that buying a house is basically like becoming a landlord and then renting the home to yourself. This makes sense because landlords and tenants don’t always see eye-to-eye, but if you are your own landlord this problem goes away.

Consequently, in my mind, the most important price in the housing market has always in my mind has always be then price-to-rent ratio. When I first started fretting about CDOs – and yes if you have forgotten it really was all about CDOs – was when the price-to-rent started to climb above 1.4.

My case at the time is that there was no way we could have faith that the models would hold in a world that no one had ever seen. The models only operate on data that they have, going to far out of sample, and you just don’t know what might happen.

Anyway, back to the question at hand – do we have too many homes. Hitherto my case has been based on units per person. We have been cranking out new homes at slower than average rates. It may look like we were building a lot of houses, but that was primarily offset by the fact that we weren’t building very many apartment buildings.

So in fact the number of housing units per person in the US is getting fairly tight. We can see something of that in the price-to-rent ratio.

The price-to-rent ratio is closing in on its long term average of 1-to-1.

However, it doesn’t look to me like there are any forces set to boost housing prices in the near term. Rates are only rising from what were record lows. Credit standards show no sign of loosening. Lots of folks have distressed credit and there are still likely a shadow inventory of used homes on the market.

On the other hand the fundamentals for rent look bright. Right now, rents are depressed primarily by a depressed economy and – in my opinion – a Fed that was slow in loosening monetary policy.

Both of those factors are set to change. Couple this with the shortage of units per person and we are looking ahead to a surge in rents. With that we will probably see a rapid increase in home building. Yet, I am betting that this time it is apartment homes that come roaring to the forefront. At the beginning this will likely contain a high fraction of build to rent, but unless rent prices can be held down we should expect a condo boom to run on its heels.

I am cuing Matt Yglesias to talk about how building restrictions over the next five to ten years are going to define cities for decades to come.

When the apartment boom comes – and the fundamentals suggest it is near at hand – will your locality be ready?

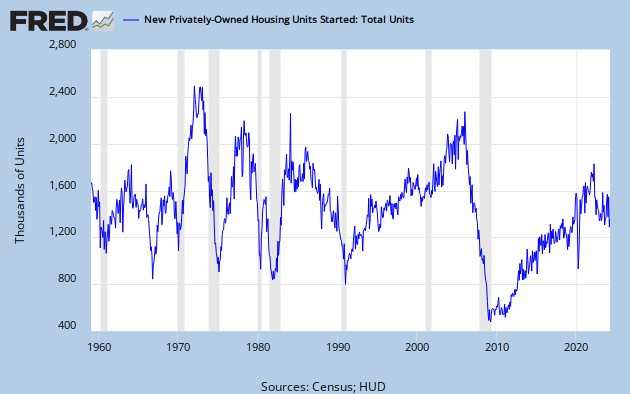

A point I want to keep emphasizing is that while the rapid increase in housing construction during the 2000s was not unprecedented, the collapse in home construction is.

This is just raw number of new units coming online. Its not adjusted for anything. So there are a lot of factors: population growth, age distribution, second-home ownership, apartments vs. single family, etc.

However, just in terms of units the peak of the boom was not way off. If there was way too much construction it has to be because the fundamentals were way different. This might well be, but understand that now the “this time is different” argument is being pushed by those who say there was a dramatic overinvestment in terms of the number of units.

Now, that’s not to say the units themselves weren’t too nice or that people were doing too much remodeling. Here is Private Fixed Residential Investment as a percent of GDP.

Though the 2000s weren’t as big as the post war boom they did out pace everything since the 1960s. Still the crash is far more unprecedented than the peak.

Another way of looking at this from a historical flow perspective is looking at how many new housing units were started each month versus how many new Americans there were each month. Again, the mildness of the run-up compared to the crash is apparent.

Indeed, because its more natural to think of people per home rather than homes per person. The implications from this view of the data I think are more instructive.

Some people die each year and some homes are torn down or condemned each year. Unless those ratios are changing rapidly then a current levels the number of persons per home will converge towards more than double its long run average.

Paul Krugman is doubting that financial collapse was a key part of the recession

My take on the US economic crisis has increasingly been that banks were less central than many people think, while the housing bubble and household debt are the key players — which is why financial stabilization by itself wasn’t enough to produce a V-shaped recovery.

I am not sure how central people think the banks were so I am not sure how hard to push back.

My take is that household debt and the banking collapse were symbiotic in their destructive nature. At the center of the story, however, is money and credit.

Highly leveraged households meant that consumers were very sensitive to economic disruption. The danger in having a lot of leverage is that when things go bad they go really bad. The flipside of course is that when things go good they go really good. We have to have some story about how things started to go bad before household debt can be invoked to explain why things went really bad.

Debt is ultimately just a promise. Lots of debt is precarious when there are many interlocking promises that depend crucially on one another. If one person flakes – as eventually one person will – the whole network could crashing down.

When the banking sector collapsed it created a huge flake. Lending fell dramatically. Projects and production that were dependent on a smooth supply of lending could not go through. This rocked many households who were themselves in locked into sensitive promissory positions.

Now knowing that a flake was possible we might step back and ask either “why did we allow such sensitive networks to develop” or “why were housing prices allowed to climb on top of these tightly wound promises”

However, the more fundamental mistake was thinking that the Fed was prepared to firewall this whole thing if it went bad. It wasn’t that people couldn’t see the debt or the housing bubble building. Its that they thought it didn’t matter. The phrase commonly thrown around was “the Fed doesn’t target asset prices.”

That’s a more convoluted way of saying, this business with housing and mortgages may be a house of cards, but “so what?”

I don’t want to sound like I am pointing fingers here. I was deeply sympathetic to that view. Sufficiently powerful monetary policy I thought, and honestly still believe, could offset virtually any shock.

What we wasn’t appreciated fully enough was the fact that monetary policy would not be powerful enough; that central bankers are only human and that they will be hesitant to take extreme action.

In the light of those limitations it becomes more important to manage precarious situations as they arise. However, from the point of view of understanding the economy we also need to note, as Matt Yglesias reminds us to do, what powerful monetary policy can indeed accomplish.

I had been urging the Fed to effectively “go negative” by promising inflation. In Sweden, the central bank went literally negative.

For a world first, the announcement came with remarkably little fanfare.

But last month, the Swedish Riksbank entered uncharted territory when it became the world’s first central bank to introduce negative interest rates on bank deposits.

Even at the deepest point of Japan’s financial crisis, the country’s central bank shied away from such a measure, which is designed to encourage commercial banks to boost lending.

The result was a surging Swedish economy. Indeed, as the FT reports, the fastest growth on record. This is coming out of a worldwide economic collapse.

This is also despite a long-run price to income profile that’s not that far off from the United States and peaked around the same time

I don’t think Krugman is doing this, but it is easy to get too caught up in thinking the macroeconomy is an extension personal finance. Having bought a house you couldn’t afford seems like a really bad situation to be in, and if everyone is in that situation then it seems like that ought to be really bad for the economy.

However, keep always in the front of your mind that a recession is not simply a series of unfortunate events. A recession is when the economy produces less. For example, the AIDS epidemic in Botswana is a horrible event for millions of people that uprooted lives and destroyed families and promises to leave a generation of orphans.

However, Botswana’s GDP growth didn’t turn negative until Lehman Brothers went under.

That a Global Financial Crisis could do what rampant death and disease could not, is an important indicator of the nature of recession.

A recession isn’t when bad things happen, whether that’s loosing your house to foreclosure or your parents to AIDS. A recession is when the economy produces less.

Somehow you have to make a link between the bad thing happening and the economy producing less. I maintain that, that link almost always runs through the supply of money and credit.

I couldn’t find the paper I want to reference but I remember reading a convincing analysis a while back that the advantage to consumers from Fannie and Freddie loans was on the order of 7 basis points.

The story was more or less that the difference between loans just over the Fannie/Freddie cap and those just under was only about 20 bps. Of that the estimated that less than half was due to the fact that the implicit federal guarantee was driving down Fannie/Freddie loan rates but that over least half was due to the fact that Fannie and Freddie’s guarantee was driving up rates on other loans.

Basically, investors had a choice: they could either by the Fannie Freddie loans with the implicit guarantee or they could buy private label mortgages with no guarantee. Obviously investors prefer to be guaranteed and so money moved from private label to Fannie/Freddie. This dropped Fannie/Freddie rates somewhat but it caused private label to rise by even more.

The moral of the story is that unless you think 7 basis points, which is .07% makes housing much more affordable, then Fannie and Freddie are not really that effective at providing affordable housing.

My question, however, is: what are the macro-economic implications of having no mortgage buyer with a guarantee.

As you can see during the crisis the spread exploded

Indeed, that was a big signal that things were going horribly wrong.

The rise in the spread during 2009 can be somewhat attributed the Fed’s buying of Fannie and Freddie bonds directly. However there was a clear jump in 07 that was related to the beginning of the housing crash.

Also its no well kept secret that Fannie and Freddie became the lender of only resort during much of the crisis. Rising to 100% by mid 2010

The question is: what would have happened to the US economy had Fannie and Freddie not been in a position to offset the collapse in the private mortgage market.

One possibility is that the price of housing would have collapsed. I know that people are still shell shocked by the decline in housing prices, but while there was a dramatic fall it was hardly a full scale collapse.

Here is the Case-Shiller 10-city index

We are still 60% above the year 2000 level, roughly where we were in 2003. Imagine a collapse all the way back to 1992 levels? This is certainly possible, it happened in Detroit.

Even bigger collapses are theoretically possible. If credit completely tightens then the market will turn to cash buyers and price will fall to the point where cash buyers can meet forced sellers.

The question is how bad would that have been macroeconomically?

On school of thought would be that reaching equilibrium faster would reduce uncertainty. It would cause a much larger wave of strategic defaults, but that on the other hand would have meant a huge decline in the debt overhand for consumers.

A key issue is whether or not the private banking sector could have been as easily saved without Fannie or Freddie. This I do not know. I would tend to think that the insolvency would have been much deeper and the success of TARP less certain.

In short, while I have little concern that the demise in Fannie or Freddie mean much for affordability I am more concerned about macroeconomic stability. Without a mortgage lender of last resort, much larger crashes in housing prices are possible and with that the possible unrescueable collapse of retail banking.

I posted a link to Bryan Caplan’s paper on Behavioral Economics and the Welfare State. Many of the comments I got from economists were predictable:

- Where is the formal model and existence proofs?

- Where is the data analysis?

- How is this a paper?

- Do you mean to tell me this is publishable?

I too was shocked initially by these features or lack thereof. However, that’s part of what made the paper compelling.

Some papers get a wonderful data set, perform magnificent identification and get a result that really changes your mind about something you care about. Most don’t.

Most are cases that are of very narrow interest or do a 90% good job at the ID but leave enough doors open that you are not really sure if the result is meaningful or not.

On the other hand, one could as Bryan and his co-author did, attack an important question, string together some non-obvious points and in my case leave the reader thinking about whether he or she should reexamine an import view.

The profession should rightly celebrate the first kind of paper. However, what about the relative worth of the second and the third?

I submit that bringing up arguments that use the economic way of thinking matter. This is true even if the argument is not definitive, has no mathematical proof behind it and marshals no data.

Let me give a more timely example. We are now engaged in a debate over the nature of recessions and how the government should respond. There are obviously lots of models and empirical studies, none of them perfect.

However, more than any other analysis the baby-sitting coop story made me a confident Keynesian. Before then I could parrot the New Keynesian models and understood that this was more or less what a smart economist was supposed to say.

However, I didn’t know how to counter the logic of Laizze Faire except to say, “well there are sticky prices and an Euler equation and so the household will adjust consumption . . . “ This is compelling to virtually no one – not even, on a deep level, to myself.

When it really came down to it, I would have been left with “Great Depression! Want it to happen again? No? Then we need to spend more money or cut taxes! Why? Because I am very smart and I have a whiteboard. Do you have a whiteboard?”

However, a simple story about baby-sitting and it all fell into place. Paul Krugman has retold the story many times. Its about a baby-sitting co-op that uses scrip to track how many times a couple has sat for other members of the co-op and thus how many times someone should sit for them.

Because of some mismanagement in the handling of scrip the co-op at one point went into recession. There weren’t any fewer people who could babysit and there weren’t any fewer opportunities for couples to go out. The real baby-sitting economy hadn’t changed.

Bad policies by the co-op leaders reduced the number of scrip per couple. And, for lack of scrip no one went out. And because no one went out, no one sat. And because no one sat, no one got any scrip. And, since no one got any scrip, no one could go out . . .

Excess demand for financial assets led to a collapse in the demand for real good and services. Something that seemed extremely complicated was elucidated by a simple story.

Years ago that story was printed in an economics journal. I read it in the Slate.com archives.

As I have mentioned before I started warning of a Japanese style scenario in early 2008, not because of a formal model, but because of that baby-sitting story.

You see, the investment banks were like a baby-sitting couple who by borrowing and lending script and carefully tracking dining out patterns with fancy computer models had assured everyone that any couple, at any time, could find a baby-sitter whether they had physical scrip or not. Just come to us, and we’ll make it happen. No scrip down as it were.

That system was about to collapse and when that happened the demand for physical scrip was going to skyrocket. If you believed the original baby-sitting story that meant a recession of epic proportions. We were going to need a lot more scrip and the Fed didn’t seem to get that.

Nor, I should mention, did may people familiar with mainstream macro-economics. Its not that you couldn’t have gotten that result out of the math models. Its that you wouldn’t have known where to look.

You would have thought about wealth effects and the distributional impact of housing. Willem Buiter, a very smart man, insisted there would be no recession because the decline in the price of houses made homeowners poorer but homebuyers richer. This does somewhere between little and nothing to the representative agents Euler equation. However, Buiter failed to consider the simple lesson of the baby-sitting economy.

Buiter, forgot about scrip.

Megan McArdle comments on the following questions

There’s a sort of fair question highlighted at Balloon Juice–why aren’t libertarians proposing solutions for the foreclosure crisis? There are serious paperwork issues, which banks seem to have tried to solve by throwing together some highly suspect legal documents. As Mistermix says, “Since the basis of libertarian philosophy is property rights, I would have expected a little more outrage from places like Reason about robo-signing”. ED Kain adds “In any case, I say mistermix’s critique is fair because it is – libertarians are not proposing meaningful solutions to the foreclosure problem as far as I can tell.”

I don’t know about the Reason guys but I can say that I was more or less hoping the whole thing would blow over and that in the wake of it we could get serious about electronic documents and get rid of the paper crap all together.

The reason I’m not more outraged is that I have seen little evidence that actual property rights were infringed. Property rights are often represented by pieces of paper but they are not created by pieces of paper. They are created by mutual consent and a meeting of minds. To my knowledge almost all of these cases involve people who believed that they were taking out a mortgage and banks who believed that they were providing a mortgage. That’s a solid transaction.

Now to the extent there were people who were tricked into certain deals, that is a problem whether the paperwork checks out or not. In those cases there was no meeting of the minds and the existence of a confirmed paper trail doesn’t change that.

There is a favoritism towards renting in the economics blogosphere, perhaps reflecting some partial irrationality of homeowners, or maybe it’s just a collective cosmopolitan ethos of econ bloggers. In either case I find it interesting to consider rational economic reasons for the strong preference for homeowners that Americans display. A recent paper by Pablo Casas-Arce and Albert Saiz explores an angle I haven’t heard before. Their argument is basically that an inefficient legal system creates a cost of renting versus owning:

In this paper we argue that, lacking alternative means of enforcement such as reputations, market participants will tend to avoid the use of contracts when operating in an environment with very inefficient courts. As a result, the legal system may alter the allocation of ownership rights.

To examine this claim we consider the housing market, where these effects are most financial intermediaries emerged in India in response to Financial regulation. transparent: essentially, a user of housing services can either buy a house or rent it from another owner or landlord. Hence, studying the prevalence of rental properties will tell us about the use of rental contracts and, hence, the allocation of ownership rights in such a market. To the extent that contracts can be enforced, they will allocate these rights in an efficient manner to maximize welfare. This will involve some individuals purchasing the houses they use, while others will buy access to them from a separate owner on an occasional basis, using a rental contract. But when these temporary transfers of control are costly to enforce, we will see departures from that optimal allocation. In particular, market participants may decide to avoid contractual disputes by relying less on rental agreements and, instead choosing a market structure that displays more direct ownership by the final user.

The part of enforcing a rental contract that can be costly in an inefficient legal system is kicking out a renter, either to evict them or simply because the landlord doesn’t want to renew the lease to them for some reason. Megan McArdle’s recent problems trying to purchase a home with a current renter is a perfect example of this. As they discovered, in D.C. it can be very difficult to remove a renter:

District of Columbia Law and Superior Court Rules prohibit the execution of evictions when a 50% or greater chance of precipitation is forecasted for the next 24 hours. Additionally, if the weather forecast calls for temperatures below 32 degrees Fahrenheit over the next 24 hours, evictions other than those designated as Commercial Property will be canceled.

Official weather determinations are made daily at 8:00am., and are based on the National Weather Service Forecast for the Ronald Reagan National Airport, formerly National Airport, the official weather location for the District of Columbia.

When evictions are canceled due to weather and the Writ expires due to no fault of the U.S. Marshals Service, the Landlord will be required to re-file for an Alias Writ and a new filing fee will be required. All Writs identified as Alias Writs and those that are about to expire, will be considered for priority scheduling.

This tells us that the recent problem involving the unclear legal status of a bunch of foreclosures, if not resolved clearly and carefully, could lead to a higher rental rate. After all, this decreases the efficiency of the ownership contract relative to the renter contract.

The lesson in the long run is that if you want more renters, for reasons of labor mobility or whatever, you should make sure the legal system related to rental contracts operates efficiently. This doesn’t necessarily mean favoring landlords over renters, but rather making contract enforcement clear and easy.

Another chart to steal from Real Time Economics, this time provided by Justin Lahart.

The classic hydraulic macro story would imply that someone is hoarding cash. It would be really nice then if we could look around and see some cash being hoarded. Indeed, we do.

A point I want to make is that none of these pieces of evidence is in-and-of itself conclusive: The small business survey, the flow of funds, inflation expectations, etc.

There could be explanations for all of them that involve something other than the traditional liquidity demand story: that is that recessions are caused by excess demand in the market for cash/bonds/safety.

However, the liquidity demand story suggests that certain things should all be happening at the same time: a decline in the demand for labor, a decline in the purchase of durables, a decline in consumer prices and business’s pricing power, a decline in asset prices, a decline in inflation expectations, an increase in cash holdings, an increase in the ease of finding workers, etc.

And, all of those things are happening.

I like to focus on inflation because I think just about all of us have agreed that inflation is primarily controlled by actions at the Fed. Thus close patterns between inflation and other variables should suggest that they are also controlled by the Fed.

Here is fraction of income spent on durables and inflation.

Ed Leamer likes to say that its all durables and housing. I think there is more going on in housing than money creation but lets check the Leamer story versus inflation.

Looking at durables only suggests that inflation might flatten out soon. Looking at durables and new houses suggests that deflation will be upon us for sure. It will be interesting to see what happens.

Note, however, that this is not saying that a reduction in income spent on durables and housing will cause a decline in inflation. Its saying the Fed has already taken certain actions. The immediate result of those actions is a decline the fraction of income spent on durables and new houses. The future impact of those same actions will be a decline in inflation.

In other words the inflation decline is already baked in. What we have to ask ourselves now is whether we want to take actions that would raise inflation expectations for the medium future.

Some time ago there was a blogospheric debate about whether a house should be considered an investment. I contended that almost necessarily it has a large investment component, and should be thought of as such. In addition, for many people -although I don’t know how many- housing can be a good investment. Felix Salmon and Ryan Avent disagreed, with Ryan arguing housing was an investment, but rarely a good one, and Felix arguing that it was not an investment at all. Today, esteemed economist Karl E. Case of Case/Shiller fame weighs in on the housing as an investment debate:

But for people with a more realistic version of the American dream, buying a house now can make a lot of sense. Think of it as an investment. The return or yield on that investment comes in two forms. First, it provides what is called “net imputed rent from owner-occupied housing.” You live in the house and so it provides you with a real flow of valuable services. This part of the yield is counted as part of national income by the Commerce Department. It is the equivalent of about a 6 percent return on your investment after maintenance and repair, and it is constant over time in real terms. Consider it this way: when Enron went belly up, shareholders ended up with nothing, but when the housing market drops, homeowners still have a house. And this benefit is tax-free…

…This financial crisis has made us all too aware that we live in a Catch-22 world: the performance of the housing market drives the economy, and the performance of the economy drives the housing market. But housing has perhaps never been a better bargain, and sooner or later buyers will regain faith, inventories will shrink to reasonable levels, prices will rise and we’ll even start building again. The American dream is not dead — it’s just taking a well-deserved rest.

Karl wants you to think of housing as an investment, and he wants you to invest. I’ll agree with him on the first point, and remain agnostic on the second.

He also makes an important point about how housing lacks any true fundamentals like financial investments do:

Real estate sales are unlike other financial transactions. You can place a rough inherent value on a stock or bond by looking at fundamentals: a company’s profits, price-to-earnings ratios, quality of its products and management, and so forth. But a house is worth what someone is willing to pay for it. That’s a very personal, emotional decision….

This lack of solid fundamentals is an important problem with identifying housing bubbles. It is entirely possible for there to be an exogenous increase in the preference for home ownership that will drive up the prices of housing, as well as the price to rent ratio. Capitalization rates, which determine how an individual translates a flow of housing services into a house price, differ among individuals. Demographics can shift in ways that will affect cap rates, for instance average income or age can increase, but so too can the raw preference for home ownership. So house prices went up 15% while rental rates remained constant; what just happened? Is this irrational speculation, or did preferences for home ownership increase?

UPDATE: Felix does some real reporting and gets Case on the phone. I am apparently interpreting his use of “investment” too literally.

I don’t have some all encompassing narrative of the housing bubble to weave you, or an airtight case that government policies caused the bubble, didn’t cause the bubble, etc. I just want to comment on a few points in the debate.

The argument is frequently made that Fannie and Freddie were minor securitizers by the time the bubble came to a full boil in 2006, therefore they didn’t “cause” the bubble. But the fact that private companies were able to push them out of the market doesn’t tell us anything about the initiation of the bubble. The fact is that as early as August 2002 Dean Baker, who many credit as having “called the bubble”, was saying that prices were becoming divorced from fundamentals. As you can see from Karl’s chart, this is still during a time period when GSEs constituted the vast majority of MBS issuance and were quickly ramping up:

So was Dean Baker identifying a bubble in late 2002 that wasn’t there, or were Fannie and Freddie the majority MBS issuers when the bubble started?

A lot of focus goes into who issued the subprime loans which are now defaulting and much less discussion occurs about what caused the initial divorce of house prices from fundamentals. I think Jim Hamilton’s explanation of the run-up in oil prices that led to the beginning of this recession has some applicability to what happened in the housing market. In short, prices skyrocketed because market participants (and academics) no longer knew the value of a key parameter. When demand did not subside even as oil prices went above historical levels, market participants began to wonder “what exactly is the price elasticity of oil at this level?”. As Hamilton put it:

Just as academics may debate what is the correct value for the price elasticity of crude oil demand, market participants can’t be certain, either. Many observers have wondered what could have been the nature of the news that sent the price of oil from $92/barrel in December 2007 to its all-time high of $145 in July 2008. Clearly it’s impossible to attribute much of this move to a major surprise that economic growth in 2008:H1 was faster than expected or that the oil production gains were more modest than anticipated. The big uncertainty, I would argue, was the value of ε. The big news of 2008:H1 was the surprising observation that even $100 oil was not going to be sufficient to prevent global quantity demanded from increasing above 85.5 mb/d.

Once the ratio of house prices to rents and other fundamentals became indisputably divorced from historical levels, market participants had to wonder what are the new underlying parameters were. Dean Baker said from the start that the historical levels were correct, and nothing has changed. Economists overall were agnostic. But from 2002 until 2007, those who bet optimistically were rewarded and those who bet pessimistically were punished or ignored as prices increased quickly.

If Fannie and Freddie drove the initial divorce of prices from their historical relationship with fundamentals, than they are an important causal factor. Yes, markets that myopically rewarded the most optimistic assessments of the new parameter values were a necessary condition for us to arrive at the hugely frothy markets of 2006, but so too was some first mover to push prices above historical levels.

Perhaps some of that divorce from fundamentals was real, in the sense that the equilibrium price to rent ratio grew as a result of a change in capitalization rates driven by income growth. If this is the case, then those who want to claim that the bubble was “called”, especially by Dean Baker, or that bubbles are identifiable, have a harder story to tell about when you know that a bubble has formed. What level of divorce from historical values is acceptable as real and at what level do you call it a bubble?

In discussing ways to stimulate the housing market, Felix Salmon wonders why we aren’t seeing more landlords buy up cheap homes to rent:

The backstory here is basically the big secular shift that Richard Florida talks about a lot, especially in his latest book. In order to have more renters we’ll need more landlords, and they don’t seem to be buying, record-low mortgage rates notwithstanding. What’s going to entice them into the market?

One way to encourage more landlords in some areas would be to remove rent controls. Allowing landlords to raise prices increases the value of the investment to them, and thus increases their willingness to pay. In most places in the country this has gone by the wayside, but according to the most recent American Housing Survey there are still 529,000 housing units subject to rent control. That’s nothing to sneeze at.

Are there any other regulatory burdens preventing people from becoming landlords? The legal documents required are pretty lengthy, but I can’t picture that being a serious impediment. Any suggestions?

It must be, because what else explains this ridiculous optimism?

In an annual survey conducted by the economists Robert J. Shiller and Karl E. Case, hundreds of new owners in four communities — Alameda County near San Francisco, Boston, Orange County south of Los Angeles, and Milwaukee — once again said they believed prices would rise about 10 percent a year for the next decade.

With minor swings in sentiment, the latest results reflect what new buyers always seem to feel. At the boom’s peak in 2005, they said prices would go up. When the market was sliding in 2008, they still said prices would go up.

The post-housing-bubble narrative has been that the unsustainability of prices was obvious ex ante, and so we should be able to call them in the future. This to me seems to be a bit of hindsight bias, but it is always difficult to make a case that claims which turn out to be ex post false were nevertheless ex ante reasonable. Kristopher Gerardi, Christopher Foote, and Paul Willen have a new paper out that I’ve been waiting for someone to write. They go through pre-collapse claims of the housing pessimists, optimists, and agnostics, and evaluate not just who was write and wrong but which beliefs where obviously right and which were debatable. This is a fun and accessible paper starring a well-known cast of characters, with prominent roles for Paul Krugman, Dean Baker, and Robert Shiller, and a quick cameo by The Economist, Calculated Risk, and John Cassidy. I strongly recommend it.

Rereading the cases of the optimists and the agnostics should be a reminder to those who claim to have identified the bubble, and also argue for the identifiability of future bubbles, with a high degree of confidence. The burden of proof on those making those claims is to argue convincingly against, for instance, Himmelberg, Mayer, and Sinai who argue that you can’t just look at price to rent ratios, but must consider changes in the user-cost of housing.

Even more prominent than the housing optimists are the housing agnostics. Rosen and Haines argued that the academic consensus on the issue was that the relationship between prices and fundamentals was sound, and that overpriced markets, if they existed at all, were limited. The authors find that the beliefs of agnostics can be summarized in this quotation from Davis, Lenhart, and Martin:

If the rent-price ratio were to rise from its level at the end of 2006 up to about its historical average value of 5 percent by mid-2012, house prices might fall by 3 percent per year, depending on rent growth over the period.

There is a tendency to call anyone who bought a home during the late stages of the bubble “irrational”, because prices were obviously unsustainable. But as the authors point out, the consensus of economists gave no indication that this was the case, and so behaving as if it wasn’t was quite reasonable for non-experts. Of course, pointing out that current prices were justified by fundamentals does not rationalize a 120% LTV negative amortization mortgage.

To those who simply point to lower lending standards as sufficient proof for a bubble, the authors offer this:

Did lax lending standards shift out the demand curve for new homes and raise house prices, or did higher house prices reduce the chance of future loan losses, thereby encouraging lenders to relax their standards? Economists will debate this issue for some time. For our part, we simply point out that an in-depth study of lending standards would have been of little help to an economist trying to learn whether the early-to-mid 2000s increase in house prices was sustainable. If one economist argued that lax standards were fueling an unsustainable surge in house prices, another could have responded that reducing credit constraints generally brings asset prices closer to fundamental values, not farther away.

I believe the case for humility about the obviousness and knowability of bubbles is underappreciated. Many, I’m sure, will simply point to the pre-bubble agnostic consensus of economists as more evidence that economists are rational expectations obsessed, over-mathematized fools who don’t know what they’re doing. I think they would benefit from a close reading of this paper.

It is a common and poor framing of the question to ask whether uncertainty is causing our current economic woes. Just as the path of GDP is more volatile and difficult to forecast than in stable growth years, the path of individual firm sales is similarly more volatile and uncertain. More uncertainty will make households and businesses save more and invest and spend less. There is nothing controversial here. The debate is about the cause of uncertainty, and here I see a troubling correlation between what people think the current villain is and what their non-recession bugaboos are. The narratives struggling to tie the current economic woes to long-run stagnating wages, an undereducated workforce, and anything Democrats do strike me as a tenuous stretch and reflect our tendency to need a compelling narrative when easy explanations do not present themselves.

I think a good test for yourself is to ask “what problems do you think are important today that you didn’t think were important in 2004, and what policies would you favor now that you would have opposed then?”. My answer is that low house prices are a problem today where I would previously said low prices are just transfers from sellers to buyers, and I would favor policies that prop them up when I would previously have opposed them. What are yours?