You are currently browsing the monthly archive for March 2011.

Adam has some interesting thoughts on Will Wilkinson’s critique of moral nativism. Will’s core thesis appears to be

The nature of the principles of universal grammar limits what can count as a natural language grammar. There is no language in which a suitably translated version of the sentence “Sock burger insofar loggerheads” counts as grammatical. Yet there have existed moralities in which cannibalism, ritual mutilation, slavery, and rape count as morally permissible. If the putative moral capacity can produce moralities that allow things that strike our judgment as monstrously immoral–if it doesn’t really rule anything out–it can’t account for the normativity of our judgments and the linguistic analogy fails.

My purely amateurish take is that native morality seems to exist and that it takes a form that is far more basic than what Will is describing here.

For example I propose this as an incorrect moral system:

It is morally right to cause great harm to Adam to prevent minor harm to Ben AND it is morally right to cause great harm to Ben to prevent minor harm to Chris AND it is morally right to cause great harm to Chris to prevent minor harm to Adam.

This system is incorrect because there is no way to assign moral weight to the harms on Adam, Ben and Chris such that this moral ordering makes sense.

In the language of mathematics our native moralism forces a partial ordering on the world of moral entities. Further a – perhaps the – relation in our partial ordering is harm.

For example, suppose we replaced “harm” in the scenario with “laughter.” Now the system is no longer morally incorrect.

Admittedly this is not well worked out but my sense is that the “moral entities” are key and that a partial ordering exists over them is important.

There are days when I think I should hang up my blogging hat and instead just continually point to a list of people that you should be reading instead of me, or if you’re reading them already then you should reread them, as they’ll probably say everything I would, much better, and then so much more. Reihan would definitely be on that list, and you should definitely read this whole thing instead of whatever else I might have written today:

There is no denying that the neoliberal order has been particularly beneficial for novelty-seeking elites, for whom the rise in geographical mobility, economic dynamism, and cultural diversity and the concomitant decline in social trust has been a boon on balance. Given that loss aversion is deeply ingrained and that most people prefer stability to novelty, the neoliberal turn may well have imposed a regressive psychic tax. The good news, from my perspective, is that our cultural make-up is being remade. America is becoming a more expressive and creative society, yet the country is also building a model of multigenerational kinship that bears more resemblance to pre-Fordist than Fordist social forms. Indeed, the specialization of women into household production was very much a post-1920s development, and our era of delayed marriage and declining birthrates, immigration-fueled diversity and densification, relative economic freedom and wage and wealth dispersion, etc., looks a fair bit like the world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, only richer and more inclusive.

At his Prefrontal Nudity blog at Forbes, Will Wilkinson discusses the comparison of morality and language. The argument is that morality is like language, in that we come with it to some extent “built in”. The theory, Moral Nativism, is inspired in part by Noam Chomsky, who argued that languages and grammar may vary across cultures and time, but there is a deep commonality among them. Furthermore, there is “insufficient information in a child’s experience to account for her acquisition of competence in the rules of grammar”. Therefore, language is not simply something we learn, but something that is built into us; humans have an “innate linguistic capacity”.

Moral Relativism takes this concept of innateness of knowledge and applies it to morals. Specifically, Rawls asked whether the experience of children was sufficient to account for the morals they possessed. Will cites Scott James who summarizes the argument thusly:

“Since kids, across a wide spectrum of backgrounds, all exhibit this ability to distinguish moral from conventional rules, is it plausible that kids could have learned this from their environment? If the answer is no (as some insist), then the mind may well contain the moral analogue of the Language Acquisition Device. And this conclusion is bolstered if we can identify (as some allegedly have) other moral competencies that kids don’t learn.”

As a rebuttal to this viewpoint, Will takes us to Jesse Prinz who presents a long list of evidence for the terrible variation in morality across time and cultures:

Anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday found evidence for cannibalism in 34% of cultures in one cross-historical sample. Or consider blood sports, such as those practiced in Roman amphitheaters, in which thousands of excited fans watched as human beings engaged in mortal combat. Killing for pleasure has also been documented among headhunting cultures, in which decapitation was sometimes pursued as a recreational activity. Many societies have also practiced extreme forms of public torture and execution, as was the case in Europe before the 18th century…

As anyone familiar with humanity’s impressive history of violence could guess, the list goes on and on. Language, Will argues, may vary greatly, but at a deeper there are many clear constraints and commonalities. Aside from those rules which are necessary for a society to thrive, pretty much anything has gone in terms of morality. As Will puts it:

If the putative moral capacity can produce moralities that allow things that strike our judgment as monstrously immoral–if it doesn’t really rule anything out–it can’t account for the normativity of our judgments and the linguistic analogy fails.

I have to say I find this evidence against moral nativism pretty convincing, just as I find it convincing evidence against moral objectivism. Another reason I’m skeptical, at least of moral objectivism, is the following thought experiment. Say you had an unlimited amount of money and time to persuade the chief of some Amazonian tribe of an objective scientific claim that the best evidence suggests is true. Say, that the earth revolves around the sun, or some other basic scientific claim. You can conduct scientific experiments, sit with him in the library going over the literature, and argue with him for 1,000 years. No matter what the starting point of his knowledge and beliefs, you should eventually be able to convince him of the truth as best as the evidence indicates, after all, its demonstratable knowledge.

Now say this tribesman believes that murdering an enemy and eating his heart pleases the Gods. With unlimited money and time, is there any way you could demonstrate to him the falseness of his beliefs? Well, you could try some Ghost of Christmas past shit and take them to see their victims mourning families and such, but in many cases this would not be successful. Those with horrifying moral beliefs are often quite aware of, and even relish in, the suffering that is caused. I also think this thought experiment would hold true for many moral beliefs that we find horrendous and those who hold them. To me this to me is an important distinction. There is simply no way to demonstrate the truth of the claim to people who disagree.

I think some of the difficulty in rejecting moral objectivism comes from the perceived implications of objecting it, rather than it’s plausibility per se. But at the end of Will’s post is a defense of moral relativism that counters many of these common objections, for instance:

Allegation: Relativism entails that we have no way to criticize Hitler.

Response: First of all, Hitler’s actions were partially based on false beliefs, rather than values (‘scientific’ racism, moral absolutism, the likelihood of world domination). Second, the problem with Hitler was not that his values were false, but that they were pernicious. Relativism does not entail that we should tolerate murderous tyranny. When someone threatens us or our way of life, we are strongly motivated to protect ourselves.

It would be worth reading Will’s post for this list alone.

Despite all these reasons to be skeptical of moral objectivism, I don’t think I can reject it with much confidence, and I should probably remain close to agnostic. Why? Well, as I’ve surely made clear by this point, I am a philosophical naif with the background knowledge of the typical economist; that is, “utilitarianism is the moral framework, Rawls said some stuff that disagreed, but what can you really do with that stuff? Now tell me your R-squared.” So why does that lead me towards moral objectivism? Because I put weight in the beliefs of experts, and (via Bryan Caplan) I can see that a slim majority of them accept or lean towards moral objectivism. Until I’m intellectually curious enough to do the hard lifting of really understanding the arguments of moral objectivists, I’ll remain near agnostic out of humility in the face of 52.4% of professional philosophers disagreeing with me.

End Note: It would he helpful to Will if you would leave some comments on this blog post over at Forbes.

Arnold Kling writes

The prices of imported intermediate inputs are being handled incorrectly. When you underestimate the rate of price decline, you also under-estimate the real amount being supplied. And because these are imported intermediate goods, the error is not neutral with respect to U.S. output.

Here is the in a simple numerical example.

Suppose in 2007 the US imported $100 of steel and made $200 of cars with 4 workers. The US added $100 worth of value with 4 workers. So each workers productivity is $25

In 2009 the US imported $50 of steel and made $150 of cars with 3 workers. Now the US is tripling the value of its imports. The US has a value-add of $100 with 3 workers. So each workers productivity is $33.

A productivity boom of 50%. GDP stays the same with fewer workers. This is part of our current problems.

But wait Mandel says, we are doing it wrong. The actual amount of steel didn’t drop in half. Its just that the price of steel fell. If price had remained constant we would have imported $75 worth of steel, had $75 of value add and worker productivity would be stuck at $25.

Moreover, US GDP value-add would have declined to $75 so our GDP would have shrank.

This is the wrong way to look at it. It doesn’t matter what the actual raw steel coming in was, it matters what we paid for the steel. Why?

Well because

- You are still getting more car per worker which makes the workers more valuable and hence more desirable to hire

- The GDP of the US is still the difference between what we create minus what the foreign imports cost.

Now you might argue that these price drops are temporary and then productivity will decline. That is a fine case. However, to the extent they are permanent – as is probably the case in electronics components – it’s a real gain.

Suppose that instead of this being a price drop in foreign steel it was a price drop in domestic steel from some fancy new steel making process. What difference would it make to US autoworkers? They are still getting the same good at a lower price. They are still able to produce more value per hour of work.

In other words improvements in the terms of trade act like a boost in productivity. Indeed, that’s the whole point of trade.

Now, Noah Smith pointed me to a paper that disputed this, which I haven’t read and may make some important points but this is the standard view and I didn’t pick up on anything in Mandel that disputed this.

Here’s a piece from David Leonhardt that has been getting some of play on blogs that I frequent. It’s definitely good to see that more of the profession are coming around to the “quasi-monetarist” view that monetary policy is not impotent at the zero bound, that it can do much more. Here’s David:

Whenever officials at the Federal Reserve confront a big decision, they have to weigh two competing risks. Are they doing too much to speed up economic growth and touching off inflation? Or are they doing too little and allowing unemployment to stay high?

It’s clear which way the Fed has erred recently. It has done too little. It stopped trying to bring down long-term interest rates early last year under the wishful assumption that a recovery had taken hold, only to be forced to reverse course by the end of year.

Given this recent history, you might think Fed officials would now be doing everything possible to ensure a solid recovery. But they’re not. Once again, many of them are worried that the Fed is doing too much. And once again, the odds are rising that it’s doing too little.

Indeed. Myself and others have been emphasizing that the passivity of the Federal Reserve in late 2008 (or, as I like to tell it, the Fed being hoodwinked by rising input costs) was indeed an abdication of its duties…but what duties are those? It’s unclear, because the nature of the Fed’s mandate allows it to slip between two opposing targets at will. Michael Belognia, of the University of Mississippi (and former Fed economist) makes a similar point in this excellent EconTalk podcast. The big issue, as I see it, is the structure of the Fed’s mandate. Kevin Drum (presumably) has a different issue in mind:

Hmmm. A big, powerful, influential group that obsesses over unemployment. Sounds like a great idea. But I wonder what kind of group that could possibly be? Some kind of organization of workers, I suppose. Too bad there’s nothing like that around.

I think this idea of “countervailing powers” needed to influence the Fed is wrong-headed. There is no clear-cut side to be on. Unions may err on the side of easy money…but then again, Wall Street likes easy money* too, when the Fed artificially holds short term rates low. It’s all very confusing. But that’s arguably great for the Fed, because confusion is wiggle room…however it’s bad for the macroeconomy, because confusion basically eliminates the communications channel, stunting the Fed’s ability to shape expectations.

Now here’s the problem as I see it: NGDP is still running below trend, and expectations of inflation are currently running too low to return to the previous trend. Notice, I said nothing about the level of employment. Unemployment is certainly a problem, but the cause of (most of the rise in) unemployment is a lower trend level of NGDP.

Given that you agree with me about the problem, which is the better solution:

- Gather a group (ostensibly of economists) to press to rewrite the Fed charter such that the Fed is now bound by a specific nominal target, and its job is to keep the long run outlook from the economy from substantially deviating from that target using any means possible.

- Find an interest group with a large focus on unemployment to back the “doves” in order to pressure the Fed into acting more aggressively.

I would back number one over number two any day. And the reason is that while I’m in the “dove” camp now, that isn’t always the case. At some time, I’ll be back in the “hawk” camp, arguing against further monetary ease. Paul Krugman has recently made the same point about using fiscal policy as a stabilization tool. My goal is to return NGDP to its previous trend, and maybe make up for some of the lost ground with above trend growth for a couple years. That would solve perhaps most of the unemployment problem.

But say it doesn’t. Say we return to a slightly higher trend NGDP growth level for the next couple years, and due to some other (perhaps “structural”) issue(s), unemployment remains above the trend rate we enjoyed during the Great Moderation. Would it be correct to say that monetary policy is still not “doing enough”? I don’t think so. At that point, we should look toward other levers of policy that can help the workforce adjust to the direction of the economy in the future.

I’m not say that is even a remotely likely scenario, I’m just trying to illustrate the complexity and possible confusion (and bad policy) that could come out of a situation that Drum seems to be advocating. Better in my mind to have a rules-based policy than an interest group-pressure based policy.

P.S. This was the first post I’ve ever written using my new Motorola XOOM tablet. It wasn’t the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but it was by no means easy. And I wanted to add some charts, but that would be particularly annoying.

*Which, of course, is not necessarily easy money, just low interest rates.

A snippet that happens to dovetail with my own views and therefore will be quoted uncritically.

Tyler also gets it wrong by suggesting we raise the status of scientists. It is engineers and business innovators more generally, whose status needs a boost. Scientists already claim too much credit for social innovation – they have little to do with most of it. Tyler also doesn’t mention over-regulation, a huge barrier to innovation.

This point cannot be made loudly or frequently enough. It might be that we prefer our modern world of rounded corners and calls to the EMS for routine chest pains.

But, understand why we don’t have the world Popular Science promised us. We don’t have it because its illegal.

I’ve thought a lot more than I’ve written about the Great Stagnation and whether or not we are simply seeing suboptimal monetary policy at the start of a new economic revolution.

Prices, properly measured, are collapsing and a subset of folks are rapidly shifting consumption towards those low cost areas. The Central Bank, failing to see this, keeps interest rates too tight. This explains a seemingly bizarre worldwide obsession with tight money at the very time that it seems most insane to say I am worse off today with a $1000 in cash than I would have been in 2000 with $1000 in cash.

For me, and I know I am an in infovore subset, there has been massive deflation.

However, the internet as the exclusive playground for infovores may be coming to an end. Social interactions may be the textiles of this new revolution. A product that almost every wants, that is suddenly becoming cheaper.

Facebook penetration is way up

The study, fielded in January of 2011, found that 51% of every teen, man or woman has a profile on this dominant site. That’s a majority of all Americans age 12-plus. And Edison Vice President Tom Webster, who presented the peek at the study in Arbitron’s monthly PPM client call, noted that the 51% is not just among those with Internet connections, but all Americans.

How is the BLS possibly supposed to measure this. I would suggest something akin to travel cost. But perhaps isolation costs. We could get this through experiments. Suppose I have a hotel which blocks Facebook and is out of range of 3G. How much does this knock off the daily rate versus other hotels with no 3G but do have Facebook access.

Even at $5 per night you you would be talking about $5*365*300M = 547B in annual GDP, priced out a zero dollars. That’s roughly 3% of national income, attributed to Facebook alone. Not advertising on Facebook mind you, but the economic value produced for users.

Is it that high? It could be lower but I could imagine it being higher possibly even $10 a night. And, of course there are increasing daily marginal costs to being cut off from Facebook. In the moderate percentage points of GDP is not unreasonable. Double digits seems unlikely but not widely implausible.

And of course, this is in theory just the beginning.

Felix Salmon once advised me that it doesn’t matter when you post a blog. People read all the time and check their feeders in the morning anyway.

Having experimented with this a bit I can say that its more or less wrong. Especially with the rise of twitter, it makes an enormous difference both in traffic and linkage when a blog piece posts.

Posting early morning or very late afternoon seems to work best.

In the early morning professional bloggers seem to be searching for their stories and pick up on an interesting tweet title. In the later afternoon they seem to be putting together their link dumps and are likewise sensitive to an interesting headline.

In keeping with long standing research headlines also seem to be a big deal. Not just with readers but with professionals as well. Presumably they are simply looking for something that will appeal to their readers. Lets say that ![]()

GOP Stupidity.

So, I am strongly inclined to believe that I must be missing something here, because this post by Mike Mandel – hat tip Tyler Cowen – seems wrong in almost every single respect. Like Mandel’s original this post also got out of hand. I tried to cut a bit, but this is still what I got.

Let me hit on some highlights.

Mandel says

Based on my analysis, I estimate that the actual productivity gains in 2007-2009 may have been very close to zero. In addition, the drop in real GDP in this period was probably significantly larger than the numbers showed. I then explore some implications for economic policy.

Its my understanding the BEA backs out productivity gains from GDP gains. So, it doesn’t make sense to say that industry level productivity is inaccurately measured and therefore GDP is wrong. It can makes sense that productivity is inaccurately attributed to the wrong industry – a conclusion we will explore more below.

The only way to get GDP wrong is either to miscount the number of goods and services sold in the US or to misestimate the price index of final goods – not intermediate goods.

Mandel goes on

If productivity was rising, then the job loss was due to a demand shortfall and could be dealt with by stimulating aggregate demand. That, in turn, helps explain why the “job problem” didn’t seem so urgent to the Obama administration, and why they spent more time on other policy issues such as healthcare and regulation.

This is backwards. The Obama administration focused on aggregate demand despite the surge in productivity. Imagine that productivity GDP actually grew during 2007 – 2009 despite a sharp rise in unemployment. That would indicate that productivity was growing like gang-busters. However, economists would be stumped. A pure NGDP guys like Summers would be forced to say “what recession”

Someone who leans heavily on industrial production numbers like myself would likewise be scrambling for an explanation. In the end we would have to say that this represents a “deep structural shift within the US economy.”

The productivity surge in other words helps the structural case because it is saying that we can in fact do more with less, not just that we are buying less.

Mandel again

With a little bit of figuring, I can calculate the performance of the top 10 industries versus the rest of the economy. So the top 10 industries had a productivity growth rate of more than 6% per year during the financial crisis, while the rest of the economy had negative productivity growth. So clearly if we want to understand the mystery of the productivity boom, we need to understand how these industries apparently did so well while the economy was tanking.

I like this approach, I do. I think deconstruction is key to unmasking what productivity means. However, I think Mandel is pushing it too far. Especially, in light of what he writes later.

Let’s start with primary metals, which includes steel, aluminum, and other metals. According to the BEA’s official statistics, real value-added in the primary metals industry–steel, aluminum and the like–rose by a total of 5.3% from 2007 to 2009 (this is a cumulative figure, rather than an annual rate). If this statistic is correct, this is a truly amazing performance by an industry which went through tough times over the past twenty years. The performance is especially inspiring given that the auto industry–one of the biggest customers for steel–was completely flattened by the crisis.

But a look at physical output–steel and aluminum production, measured in tons–tells a much different story. In fact, over this two year period, steel production cratered by more than 40%. Aluminum production wasn’t hit as badly, but it too fell. And the Federal Reserve’s industrial production index for primary metals fell sharply as well.

Unless I am missing something what is going on is pretty clear. As the price of raw materials rose in the lead up to the recession measured productivity stalled. As prices collapsed measured productivity soared.

On one level this is completely real because it measures the extent to which we are getting more out of labor. If suddenly someone discovered a new deposit of virtually unlimited raw materials that would be a wonderful improvement for most workers. It wouldn’t be an innovative increase in productivity but it would represent more low-hanging fruit in Tyler’s words.

On another a deeper level is represents the resilience of American production. Essentially, it saying when raw materials became more scarce we found a way to make do make the same amount with less, then when bounty returned we produced more.

Mandel goes on to make more or less the same point about computers

First, real gross output fell by about 6%. If you think of that as sales of domestically produced electronics equipment, adjusted for inflation, that sounds about right. Second–and this is the weird one–the official data apparently shows that intermediate inputs fell by 27%. In other words, to produce 6% less gross output over the course of two years, manufacturers managed to figure out a way to use 27% less inputs, both imported and domestic, in only two years.

This apparent fall in intermediate inputs is what drives the entire stellar productivity performance of the industry. So now we must ask ourselves the question: Is it reasonable that domestic electronics manufacturers could achieve such efficiencies in only two years that they could produce almost as much output with so much less input? In theory, I guess it can’t be ruled out.

We would expect that as U.S. IT hardware companies outsourced more and more of their manufacturing and services to Asia, the ratio of intermediate inputs to output would have gone up. After all, the IT industry is the world champion in outsourcing. But when we look at the data, we see something weird.

Again here cost is a potential driver though the gains are even more firm here than in materials. In materials we might argue that as China begins to rebuild those productivity gains will actually reverse. In computers not so much.

More Mandel

The official data are even harder to believe when it comes to imports. We all know that anything electronic that you buy is packed full of imported components. But according to the official numbers, imported intermediate inputs have been falling as a share of gross output, to well under 10%. Odd.

Is this really odd? I don’t know the real number but certainly the tech guys make it sound as if the actual cost of the “stuff” that goes in your phone is like $10, which is why the price of all phones eventually tends towards zero.

The cost of phones they say is the cost of engineering, design and programming. They use early adopters to make back those costs and then once they are done they sell the last few units at production costs which are barely distinguishable from zero.

To the extent Apple can squeeze it suppliers while producing really high valued products this seems like the essence of productivity growth. We have both lower input costs and higher value for the consumer.

Mandel even has a graph that shows this

He says

This makes no sense at all. It simply doesn’t fit with the evidence of our eyes.

Really? It seem perfectly consistent.

I have been saying for a long time that we are reaching the end of “stuff.” Indeed, that is part of our structural problem. Bigger isn’t better anymore. So the people whose job it is to provide the actual parts are not only less essential but outright unwanted. There really are areas where we are reaching zero marginal product in the gross manipulation of materials. That is the bending of steel and shaping of plastic.

What is valued are those products in a smarter configuration. Better recipes, I think Arnold Kling says.

Mandel in his explanations says

Three, in product categories with declining prices and rapid model changes–such as cell phones, computers, consumer electronics–the official import price indices underestimate the size of the price decline for product categories with rapid model changes (I call this the ‘Nakamura-Steinsson effect,’ after the two economists who discovered it). The reason is simple–when a new model of an imported good is introduced, the BLS typically treats it as a new good, and misses all the price decline from one model to its successor

Now you are speaking my language. If what are really saying is that the productivity gains are happening in foreign county then I can buy that.

However, this still shouldn’t affect final GDP or productivity per hour of US workers. An improvement in the terms of trade, which is what Mandel is identifying, is a productivity improvement for US workers. Its not based on US innovation, but it does lead to more output per US worker.

Mandel goes starts his conclusion

First, the measured rapid productivity growth allowed the Obama Administration to treat the jobs crisis as purely one of a demand shortfall rather than worrying about structural problems in the economy. Moreover, the relatively small size of the reported real GDP drop probably convinced the Obama economists that their stimulus package had been effective, and that it was only a matter of time before the economy recovered.

A more accurate reading on the economy would have–perhaps–cause the Obama Administration to spend more time and political capital on the jobs crisis, rather than on health care. In some sense, the results of the election of 2010 may reflect this mismatch between the optimistic Obama rhetoric and the facts on the ground.

Again this seems confused. Measured productivity growth undercuts the demand story. The small size in the fall of real GDP, wasn’t mis-measured even if everything Mandel says is true.

Here I think we finally have a meeting of the minds

But there’s a broader issue as well. As we saw above, the mismeasurement problem obscures the growing globalization of the U.S. economy, which may in fact be the key trend over the past ten years. Policymakers look at strong productivity growth, and think they are seeing a positive indicator about the domestic economy. In fact, the mismeasurement problem means that the reported strong productivity growth includes some combination of domestic productivity growth, productivity growth at foreign suppliers, and productivity growth ”in the supply chain’ . That is, if U.S. companies were able to intensify the efficiency of their offshoring during the crisis, that would show up as a gain in domestic productivity. (The best case is probably Apple, which has done a great job in managing its supply chain for the iPod, iPhone and iPad and extracting rents).

From an economic and policy point of view, there’s a big difference between purely domestic productivity gains, productivity gains at foreign suppliers, and productivity gains ‘in the supply chain’. The benefits of domestic productivity gains will like accrue to the broad array of production and nonproduction workers in the U.S. The benefits of productivity gains ‘in the supply chain’ will likely go to the executives and professionals, both in the U.S. and outside, who set up, maintain, improve, and control supply chains. That’s a much smaller, globally mobile group. And the benefits of productivity gains at foreign suppliers? Well, that depends on how much power U.S. buyers have vis-a-vis their suppliers…that is, competitiveness.

Ok, yes and no.

Its definitely the case that intensifying the efficiency of your offshoring supply chain would show up as a productivity gain, and that is completely consistent with what the statistics are supposed to tell us.

On Mandel’s second point, that this means that gains are likely to accrue to supper stars – maybe. It depends on how rare supply chain thing management skills are. If everyone and his brother where Skypeing China to get the lowest input price then would expect broad gains in the US economy.

If it takes special skills and contacts to penetrate the offshoring market then rents will accrue.

Further, if only certain products are offshorable, then those who own the limiting factors of their production will benefit disproportionally.

Economists like to say that buying a house is basically like becoming a landlord and then renting the home to yourself. This makes sense because landlords and tenants don’t always see eye-to-eye, but if you are your own landlord this problem goes away.

Consequently, in my mind, the most important price in the housing market has always in my mind has always be then price-to-rent ratio. When I first started fretting about CDOs – and yes if you have forgotten it really was all about CDOs – was when the price-to-rent started to climb above 1.4.

My case at the time is that there was no way we could have faith that the models would hold in a world that no one had ever seen. The models only operate on data that they have, going to far out of sample, and you just don’t know what might happen.

Anyway, back to the question at hand – do we have too many homes. Hitherto my case has been based on units per person. We have been cranking out new homes at slower than average rates. It may look like we were building a lot of houses, but that was primarily offset by the fact that we weren’t building very many apartment buildings.

So in fact the number of housing units per person in the US is getting fairly tight. We can see something of that in the price-to-rent ratio.

The price-to-rent ratio is closing in on its long term average of 1-to-1.

However, it doesn’t look to me like there are any forces set to boost housing prices in the near term. Rates are only rising from what were record lows. Credit standards show no sign of loosening. Lots of folks have distressed credit and there are still likely a shadow inventory of used homes on the market.

On the other hand the fundamentals for rent look bright. Right now, rents are depressed primarily by a depressed economy and – in my opinion – a Fed that was slow in loosening monetary policy.

Both of those factors are set to change. Couple this with the shortage of units per person and we are looking ahead to a surge in rents. With that we will probably see a rapid increase in home building. Yet, I am betting that this time it is apartment homes that come roaring to the forefront. At the beginning this will likely contain a high fraction of build to rent, but unless rent prices can be held down we should expect a condo boom to run on its heels.

I am cuing Matt Yglesias to talk about how building restrictions over the next five to ten years are going to define cities for decades to come.

When the apartment boom comes – and the fundamentals suggest it is near at hand – will your locality be ready?

Krugman is seeing between the lines. He writes

One thing Mike fails to note is that the recent AEI paper on deficit reduction, which is cited by that JEC study in a way that might make you think that it supports the case for expansionary austerity, actually never provides any evidence to that effect; it focuses only on deficit reduction as an end in itself. In fact, it comes close to conceding defeat on the issue:

Actually the JEC report doesn’t even say that cutting spending is expansionary. It lays out a mechanism through which it might not be contractionary and the layers on a bunch of asterisks. The baseline conclusion of someone reading the report is that all the asterisks are there because they don’t really believe what they are saying is likely. However, someone asked them to put together a report showing that its possible.

I mean anything is possible right. I can read the report again but I don’t even think it describes expansion as likely at any point. Theoretically possible is the most the authors are willing to give.

The authors are the GOP staff, mind you.

My larger point is that economists doing their best to do economics aren’t that far a part. That is not to say there aren’t big policy disputes, but to a large extent these revolve around which elements of the analysis you care about.

The point of the JEC report is that cutting government is great, releases resources for the privates sector and could possibly not damage the overall economy.

In pure economics this doesn’t really contradict Krugman. If your value for government spending is low enough – perhaps even negative for some folks – then this argument makes sense.

PS

Let me go into more detail quickly about the art of the “possible.” From the GOP staff report

Consequently, fiscal consolidation programs that reduce government spending decrease short-term uncertainty about taxes and diminish the specter of large tax increases in the future for both households and businesses. These “non-Keynesian” factors can boost GDP growth in the short term as well as the long term because:

You might be inclined to read this as if the authors are saying GDP could grow as a result of the fiscal consolidation because of factors they are about to list.

Yet, that’s not what those sentences actually say. They say the non-Keynesian factors can boost GDP.

That is, after the you account for the loss in employment due to government consolidation that you shouldn’t stop there. It is conceivable that GDP will be higher than the depressed level that Keynesian analysis would predict because of non-Keynesian factors.

Its not saying that it would higher than baseline. Just higher than Keynesian analysis would predict and that it is conceivable that this could happen.

Or tellingly they also say

In some cases, these “non-Keynesian” effects may be strong enough to make fiscal consolidation programs expansionary in the short term as well the long term. A number of developed countries have successfully reduced government spending, government budget deficits, and stabilized the level of government debt. Fiscal consolidation programs in Canada, Sweden, and New Zealand, among others, achieved their goals for government deficit reduction and government debt stabilization and boosted their real GDP growth rates by reducing government spending

Again you might be tempted to read this as: I am giving you some examples in which austerity caused short term growth. Again, that is not what this says.

Its says three things

- There are “some cases” – note the cases need not actually exist in the real world – in which short term non-Keynesian effects are strong enough to overwhelm the Keynesian effects that we readily admit occur.

- There are also some countries that have actually reduced government spending as a percentage of GDP. Note, I did not say these countries were the same as the cases I hypothesized above.

- In these cases real GDP growth rates were increased by reducing government spending. Note, I did not say when this increase occurred or whether or not it was cyclical or long run. In the cases presented below the evidence is largely than they were long run.

I did a blogging heads with Megan Mcardle that’s up this morning. I don’t think Modeled Behavior’s host lets me pop in anything but pictures and videos that are verified by YouTube, but you can find the whole thing here.

A couple of points on content.

- I see with both this and the last one with Robin that I might have a tendency to give to much space to the other side. l tend to think of the discussion as trying to understand and come to common ground but in the realm of talking heads its probably more engaging for the viewers to push harder on my point of view

- The point I didn’t get out about the multipliers is that they forecast how much the overall economy will grow in response to government stimulus. If you were to get them high enough – in the mid 3s – then stimulus pays for itself during a recession. That is, the economy grows so much from stimulus that tax revenue will increase and the effect on the deficit will be negative. Most economists regard this as highly unlikely.

- The point I didn’t get out about the Greenspan commission is that it did come at the point of crisis and it did solve the problem primarily by raising short term taxes, though there were so longer run benefit cuts. However, in general it was in the spirit of – when the shit hits the fan the government does move on the problem.

- I want to give Megan a chance to explain her numbers but I think based on this projection from the CBO, I was more or less right about inflow and outflows.

In 2035 the estimated gap peaks with 6% of GDP in outflow and around 4.5% in inflow for a gap of 1.5% of GDP. That’s also a 75% funding level. A payroll tax increase of 1.55 percentage points for both the employer and the employee would clear the gap. That’s not nothing but its not exactly Armageddon. To put into perspective from 1980 to 1990 the payroll tax increased 1.1 percentage points for both employers and employees and that was the primary mechanism that the Greenspan commission used to close the gap.

In 2035 the estimated gap peaks with 6% of GDP in outflow and around 4.5% in inflow for a gap of 1.5% of GDP. That’s also a 75% funding level. A payroll tax increase of 1.55 percentage points for both the employer and the employee would clear the gap. That’s not nothing but its not exactly Armageddon. To put into perspective from 1980 to 1990 the payroll tax increased 1.1 percentage points for both employers and employees and that was the primary mechanism that the Greenspan commission used to close the gap. - As a larger point I agree that if we could create a more optimal tax and spending system then we would have a more optimal tax and spending system. Yet, I don’t see anything in the current environment numbers wise that points to us having a fatal tax and spending system.

- We didn’t get into health care entitlements which are a totally separate issue and I think bring up different points about social preferences, morality and politics, etc.

PS.

In the comments on BHTV Conn Carroll points to the following chart as scary but it more or less shows how trivial the projected problem is in the medium term.

The primary surplus line tells us how much SS will cost if we treat the trust fund as fictional, which is my preferred accounting method. In that case, we average a deficit in the neighborhood of $50B a year for the next ten years. Starts at 37B and grows to $118B.

Which is to say that the drain on the general fund from Social Security is slightly less than the drain from AG subsidies.

James Bullard is looking to let up on the gas. Via Bloomberg:

“If the economy is as strong as I think it is then I think it may be reasonable to send a signal to markets that we’re going to start withdrawing our stimulus, and I’d start by pulling up a little bit short on the QE2 program,” Bullard said. “We can’t be as accommodative as we are today for too long, we’ll create a lot of inflation if we do that.”

I agree that the fundamentals are looking good despite oil price increases and the turmoil from Japan.

However, I am skeptical about attempts to lay off the gas. The Fed often repeats its concern over maintaining credibility as an inflation fighter. Just as important is maintaining credibility as an unemployment fighter. A Fed that clearly sits on the sideline while unemployment remains high sends the signal to firms that future dips in demand will not be offset and thus they should be more more contractionary during periods of uncertainty.

An evolving thesis of mine, pulling on research from fellow bloggers Bryan Caplan and Robin Hanson among others, is that a more complete theory of public choice has got to be a theory of public moral sentiment.

When voters vote the likelihood that they will swing the election is so low that it doesn’t make sense to vote in a narrowly self-seeking way. If all you cared about was your own personal interest it would be best not to vote at all.

So, given that a voter votes he or she is likely voting on the basis of something else. My working theory at this point – hat tip to Andrew Gellman – is that voters have moral preferences over all of humanity and perhaps all of nature itself.

Moral preferences are relatively weak in comparison to narrow self-interest but they are extremely broad. That is we don’t care as strongly about the right thing happening as we do about good things happening to us and our loved ones, but we care about the right thing happening in a huge number of cases that have virtually nothing to do with us or our loved ones.

In the voting booth, however, people are presented with a unique opportunity. Here their choice has a very low likelihood of making a difference but it potentially makes a very broad difference. This is where we should see weak but broad moral preferences completely swamp strong but narrow self-interest.

Thus we should expect votes to be more dependent on what people think is morally right than on what people think is in their best interest.

I had picked up from the work of John Haidt that Conservatives and Liberals have different moral foundations. I assumed that this was largely due to a combination of genetics and peer influences.

However, Will Wilkinson points out some research that shows specific cuing effects can turn up or turn down the foundations of Conservative and Liberal morality.

Wright and Baril argue, drawing on an array of evidence that conservatives are more averse to threat, instability, and uncertainty, that a sense of threat tends to activate the binding foundations, producing more conservative moralities. In the absence of a sense of threat, or when exhausted from the effort of keeping our conservative moral emotions inflamed, we default to the relatively effortless liberal, individualizing foundations.

What it sounds to me Wright and Baril are saying is that the liberal setting is the one we tend toward when our defenses are down. That is, liberal morality is the morality of comfortable security.

What makes this interesting is that liberal voting tends to increase economic security. For better or worse one of the consequences of redistribution is to limit the variance in economic outcomes. This should give more people a sense of security, which would in turn shift more folks towards the liberal axis.

It all depends on the strength of various effects but what you could get is a self-reinforcing liberalism. Something happens – maybe a rapid rise in productivity – that makes people feel more secure. The security makes their moral sentiments more liberal. More liberal moral sentiments lead them to vote for redistributionist policies. Redistributionist policies increase the sense of economic security further strengthening the liberal voting trend.

I am thinking in terms of liberalism here because it seems to be growing in strength over time, which is of course consistent with rising economic security from technological progress.

However, the self-reinforcing nature produces the possibility for multiple equlibria and the notion that a single event could kick a nation from one level of liberalism to another.

Paul Krugman queuing off of Matt Yglesias writes

. . . there would be no reason to expect a general fall in wages to raise employment.

Why? Don’t demand curves usually slope downward? Yes, but that’s because when you cut the price of something, it normally gets cheaper relative to other things, leading people to redistribute their spending toward the cheaper good.

But when you cut the price of everything — which is more or less what happens when wages fall across the board — there’s nothing else to substitute away from.

Krugman’s logic seem to go like this, wages fall in all industries, income falls, consumption falls and we hit a new equilibrium with lower wages and prices. However, real wages stay the same. In a liquidity trap purely nominal moves can’t help you.

The economic case presented in the GOP Staff Commentary isn’t that cutting government workers would push out aggregate demand by driving down the price level. Its that firing government workers would drive down real wages in the private sector and thus drive up private sector employment. That is, to say that the fall in wages would be greater than the fall in prices.

Even in a recession of this magnitude that seems more or less correct. If we think that job market clears stochastically – sorry Ezra – then flooding the market with higher skilled workers should on net increase private sector employment.

It more or less must be the case that this come at the expense of total employment. We can imagine a human story to see how this works. The government fires a bunch of people. Many of them have a hard time finding work. However, one of them is a great statictian who the private sector would have loved to have, but she preferred the work she was doing at NOAA. Perhaps, the private sector could have lured her away with a multimillion dollar contract but it wasn’t willing to do that.

Now she is unemployed, needs to pay her mortgage and the private sector can snap her up at more or less market rate. This increases private sector employment, private sector productivity and private sector profits all in one swoop.

However, it does it both at the expense of this worker’s desired employment, the quality of the work done at NOAA and at the expense of other workers who are now on the unemployment line. The undertone in the commentary brushes aside but does not seem to deny these effects.

Further, the Staff Commentary seems to suggest that this effect is just one of several that will boost private sector employment. They seemed to be making the primary point that reductions now would raise the credibility of long term reductions and thus through permanent income effects raise spending.

However, again Progressives bury the lede. Here is the key phrase from the entire report, smack center in the conclusion.

Keynesians warn that significant federal spending reductions now would weaken the current economic recovery. During the last two decades, however, numerous studies have identified expansionary “non-Keynesian” effects from government spending reductions that offset at least some and possibly all of the contractionary “Keynesian” effects on aggregate demand.

What do we learn from this

- The GOP staff is Keynesian even if they are not “Keynesian.” That is they readily accept that Keynesian effects occur even if they don’t want Keynesian policy.

- Their rejoinder is that there are some effects which offset some and possibly (read: I mean anything is possible) all of the contractionary Keynesian effects.

Robert Murphy Someone entirely different (sorry Bob) says in the comments

Homeownership rates are still well above historical norms. We were way overexpanded, even if that doesn’t show up in the aggregates you are using. You do keep emphasizing your point, but I don’t see how it can adequately explain the behavior of ownership rates.

Right but homes and homeownership are not the same. Many people rent homes. Presumably people with worse credit are more likely to rent and a decline in credit standards would move some renters to buying.

However, the distribution of homeownership is different than the number of homes per person. For example, even here in humble Raleigh we saw apartments selling their units during the boom as condos. This would drive up homeownership but do nothing to create more homes.

I would presume we also saw fewer people with home trails. I don’t know the standard term but in the past you saw big savers buy a starter home, keep saving for a down payment and then buy a second home and rent the starter. Then buy a third home later and rent the first two.

As housing prices rose, the incentive to sell an old home rose and the difficulty of putting together a down payment for a new home rose, so I would assume these home trails shortened.

So these are the basic stories where you could see a difference. I don’t know what the data on them are but the core point is that thinking about how many people own homes is separate question from how many homes there are per person.

PS

One major change over time has been a decline in the fraction of new home units that are in structures with 5 units are more. Presumably the 5 unit or more structures are more likely to be rented. So this suggests a much smaller fraction of rentals coming online.

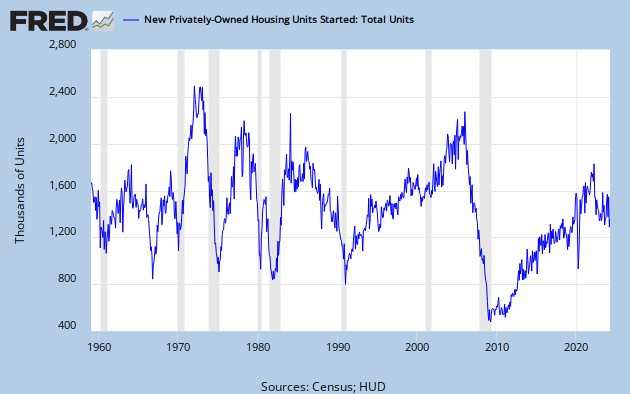

A point I want to keep emphasizing is that while the rapid increase in housing construction during the 2000s was not unprecedented, the collapse in home construction is.

This is just raw number of new units coming online. Its not adjusted for anything. So there are a lot of factors: population growth, age distribution, second-home ownership, apartments vs. single family, etc.

However, just in terms of units the peak of the boom was not way off. If there was way too much construction it has to be because the fundamentals were way different. This might well be, but understand that now the “this time is different” argument is being pushed by those who say there was a dramatic overinvestment in terms of the number of units.

Now, that’s not to say the units themselves weren’t too nice or that people were doing too much remodeling. Here is Private Fixed Residential Investment as a percent of GDP.

Though the 2000s weren’t as big as the post war boom they did out pace everything since the 1960s. Still the crash is far more unprecedented than the peak.

Another way of looking at this from a historical flow perspective is looking at how many new housing units were started each month versus how many new Americans there were each month. Again, the mildness of the run-up compared to the crash is apparent.

Indeed, because its more natural to think of people per home rather than homes per person. The implications from this view of the data I think are more instructive.

Some people die each year and some homes are torn down or condemned each year. Unless those ratios are changing rapidly then a current levels the number of persons per home will converge towards more than double its long run average.

He’s always taking hiatuses from blogging, and claiming to be “travelling”. Now I know that he has been leading a double life. From Romer’s interview with Ezra Klein:

EK:You’ve also criticized the Federal Reserve for not doing more. What would you like to see them doing?

CR:I’m teaching a course this semester on macro policy from the Depression to today. One thing I had the class read was Ben Bernanke’s 2002 paper on self-induced paralysis in Japan and all the things they should’ve been doing. My reaction to it was, ‘I wish Ben would read this again.’ It was a shame to do a round of quantitative easing and put a number on it. Why not just do it until it helped the economy? That’s how you get the real expectations effect. So I would’ve made the quantitative easing bigger. If you look at the Fed futures market, people are expecting them to raise interest rates sooner than I think the Fed is likely to raise them. So I think something is going wrong with their communications policy. They could say we’re not going to raise the rate until X date. Those would be two concrete things that wouldn’t be difficult for them to do. More radically, they could go to a price-level target, which would allow inflation to be higher than the target for a few years in order to compensate for the past few years, when it’s been lower than the target.

All kidding aside, this is policy advice gold. I can broadly agree with all that Romer is saying in the whole thing. I’m not gung-ho about using fiscal policy and expecting it to “work” in the sense that it raises NGDP to a level which is consistent with returning to trend quickly (especially with a conservative central bank), however I don’t see anything wrong with smoothing the edges of recession by helping people through the tough time using fiscal policy (mostly simple transfers), and of course reducing employment during a recession. As prescribed here (not by Mark Thoma, but by a paper circulated by John Boehner), is asinine.

P.S. I think that the level of suffering an economy would have to deal with as the result of sharp deficit reduction is directly related to the willingness of a central bank to accommodate the policy.

I was browsing around the Brookings site, looking for papers that I might find interesting, and I stumbled across an article by Peter W. Singer which analyzed survey results from 1,000+ “Millennials” who are deemed to be interested in future governance. I put Millennials in quotes because I’m often confused by generational markers, but Singer seems to define “Millennial” as “born between 1980 and 2005”. That’s a pretty large time span, but I’ll accept it. Anyway, I was interested in learning what how well my views coincided with the things Millennials found important. There isn’t anything too earth-shattering in the paper if you have a general idea of polling of young voters, but here the statistics.

- Most of the survey participants identified as Democrats (38%), followed by Independents (29%). I draw the conclusion from later data that Independents in this group largely identified as left-liberal. These two groups together, assuming I’m correct, swamped Republican identification, which stood at 26%.

- Most of the participants cited news organization websites as their highest priority news sources, with cable news following behind. Blogs and comedy shows like The Daily Show were low. Surprisingly, most cited parental influence on their political views, with other popular leaders (political, faith, celebrities) having a very low share.

- Not surprisingly, schoolbooks are defining the historical narrative, with Franklin Delano Roosevelt being their ideal leader from history, followed by Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. Barack Obama personifies “leadership needed” in the 21st century.

- Unfortunately, in my view, these participants view China as a “problem country” in the future, and few view China as an ally. I think this is driven by popular discourse, which I view as wrong and wrong-headed…and now actively damaging.

- Very good news, however, is that a majority (57.6%) think the US is “too involved in global affairs”. Also on the positive side, among the least important “challenges for the future” is immigration. I’m very interested in changing the discourse and the tide surrounding immigration in the future. It is the cheapest, easiest, and fastest way in which we can raise the poor out of poverty, and greatly increase the welfare of everyone in the world.

- On the down side, terrorism is a large priority for the participants (31.6% saying its the top). Not surprisingly, Republicans dominate the group who thinks this (at 52%), and 84% of participants think terrorism will always be a threat. No disrespect to those who have lost their lives due to terrorism, but I barely see terrorism as a “threat” at all. Indeed, I, and the majority of people in the developed world have never experienced terrorism as a “threat”, existential or otherwise. There may be incidences of terrorism in the future, and they may involve a high-profile loss of life…but I don’t think that policy should be in any way dominated by the existence of such rare possibilities.

On the whole, as should be no surprise to people who follow demographic trends, younger people seem to be more left-liberal on issues. This survey didn’t really deal with domestic social policy, and didn’t deal with economic policy at all…but I think that by and large that identification has a lot to do with social issues like gay rights, abortions, etc. I am optimistic that our young leaders will be more “libraltarian”, which is definitely a good thing in my mind. No, there will of course not be a libertarian revolution, and policy probably won’t get outwardly “better” (i.e. we’ll probably have to deal with the income tax, and onerous licensing and regulation), but I think that on some important margins, the future looks bright.

In my days in the telecom industry, I dealt with one of the largest former deals of a carrier reselling spectrum branded through another carrier. For a short while, Qwest Communications had a deal with Sprint where Qwest would resell Sprint’s wireless service, branded as Qwest, using the Sprint spectrum. These are my own observations from that situation. Think of this post as a complement to the posts about how entry into the wireless market is very hard.

This was a nightmare (and killed the enterprise) for multiple reasons:

- The provision of service, and the perception of branding. Because the service was Qwest branded, people rightfully assumed that Qwest was the company they were receiving wireless service from. This means that Qwest had to invest in support for both technical and billing services. In practice, this was a disaster. Billing wasn’t a big deal, since Qwest had a very large billing apparatus at its disposal (arguably larger than Sprint’s). Wireline carriers have a comparative advantage in billing. However, technical support was a jumble between what Qwest could handle, and was Sprint needed to handle. Not to mention the fact that beyond that, phone manufacturers were another layer of bureaucracy. There was rarely a line drawn, and customers ended up frustrated by the fragmentation.

- The handset market. The United States is unique in the world in the way we use carriers as “gatekeepers”. That is, that handsets are carrier specific. This creates very large annoyances by itself, but in reselling service, it becomes a quagmire. Qwest had many problems keeping up with mobile phone demand, even before iPhone Android. The latest phones Sprint was offering would be late or never to arrive on the Qwest network, and would essentially pit Qwest in competition with its own partner. Is the convenience of a wireless bill coupled with your home phone/tv/internet bill really worth it if you don’t have access to the latest technology? Usually not.

- Large fixed costs in licensing which couldn’t be offset by the prices of wireless service. Qwest was amazingly ambitious with pricing in the beginning of their wireless enterprise. Pioneering such conveniences as “5% bundled discount”, “unlimited minutes at 7” and “unlimited data”. This was a very large mistake that went out the window very quickly. These plans were arguably great for consumers, but they couldn’t be sustained in the arrangement Qwest had, because the costs of licensing the spectrum were too large. Qwest wanted to make a large splash, and they didn’t do a bad job…but the PR after they had to rescind these deals was very damaging. People just didn’t flock to Qwest Wireless, for obvious reasons of the cellular market being very sticky. It was a brilliant marketing move executed at the wrong time by the wrong player. They were expecting a larger migration…but large migrations are not characteristic of wireless service because of the fact that it is a rather fixed investment in the US.

Qwest (or CenturyTel) now resells Verizon, but simply deals with billing. That is, they include Verizon on their own bill, and offer a slight discount for bundled service. This is a much better arrangement given the realities of number one. However, Qwest was really done in by artificial scarcity of wireless spectrum and to a lesser extent the market structure. Licensing Sprint’s network was phenomenally expensive. The costs didn’t allow Qwest to differentiate their product, and make even a tiny splash in the broader wireless market. This could have been different had the costs of owning spectrum been lower…as they probably would be in a market, especially for higher frequencies.

It is interesting to note that US West owned a portion of very low frequency spectrum that they built out in certain markets for wireless service. US West used to offer cell phones that, in the 14 markets they covered, offered the best service anywhere (remember, this is the late 90’s). That spectrum was sold to Verizon.

The question in the title is a very ambitious question, and one that I don’t have the answer to. It has been a long time since I’ve spent any amount of energy studying the telecom industry from an investment and market perspective. Its something that I used to do when I worked for the “baby-Bell” Qwest (which has since been bought). However, I’ve always been interested in telecom, an interest that stemmed from my mother’s career with AT&T (then Northwestern Bell, then US West, then Qwest). However, no one cares about competition in wireline service anymore, almost to the point where TAP seems redundant. I once wrote an e-mail to the CEO of Qwest urging him to license their physical copper, and focus investment on FTTN and FTTH. That obviously didn’t happen. As a fun fact, if you’ve ever toured a telecom CO, it’s fairly appalling, dirty, and messy. Reflecting little ongoing investment in old technologies.

In any case, the AT&T/T-Mobile merger has caused quite a firestorm, with predictable lines being drawn. Someone else given the time and incentive will have to definitively answer the questions of the effects on competition, the consumer, and the relative market power granted by the deal. I’ll be honest, due to the sticky nature of the market, I have a vested interest in prices rising. I am grandfathered in at my contract rate, which includes unlimited data, and any extra revenue that I don’t have to give the company pays me dividends.

In any case, I see a much different problem that is at the core of this deal. AT&T has made it fairly clear that they are purchasing T-Mobile for their assets, most notably, their network technology…which actually means the spectrum bandwidth that T-Mobile owns. Now, AT&T along with Verizon own ~90% of the 700Mhz band in large markets. This is “good spectrum”, because lower frequency has an easier time penetrating things like cement and hills. However, most data seems to be carried on higher frequency spectrum, which obviously degrades signal. I’m not exactly sure of the spectrum that T-Mobile owns, but if it is lower frequency, it would actually be a boon for AT&T, which seems to have problems with data connectivity.

But the real problem is the FCC. The way in which we ration the wireless spectrum is abhorrent, and very political. Resale of spectrum is almost unheard of simply due to the one fact alone. If there was a market in spectrum usage, it is likely that AT&T wouldn’t need a deal like the one they are proposing, they could just strike a deal to either license or buy spectrum from someone else at a reasonable market price. The could bargain spectrum which doesn’t suit their needs so well for a range that does. There could be all sorts of highly beneficial transactions, if only there was market established. There is, of course, no market established…so the only cost-beneficial course for companies to take is to gobble eachother up in order to attain certain assets.

Wireline service was arguably a natural monopoly, and continues to be a largely geographic monopoly to this day. “Competition” in wireline service is one of the most confusing things you’ll ever peer into. This need not be so with something as modular as wireless, but the FCC is ensuring that wireline model is ported over to wireless service. THAT is what is hurting consumers. Perhaps regulators shouldn’t let this deal go through…but they should also realize that they created the conditions for this deal to be pursued in the first place. They’re setting the fires they subsequently try to put out. It seems like a lot of time and energy being spent to make us poorer than we otherwise would be with a simple free market.

It would also be an interesting twist for the FCC to tell AT&T to drop the deal and in return, they’d be able to license the extra spectrum they apparently need. That isn’t an optimal solution, but one I’d be interested to see unfold.

Ygelsias says

Federal spending cuts shrink the federal budget deficit and constitute a negative shock to aggregate demand. States have to balance their budgets, so the alternative to a lower level of spending would be a higher level of taxes. In AD terms, it’s basically going to be a wash either way. Its the failure of congress to enact some kind of state/local bailout appropriation that’s forcing the anti-stimulative state level stuff.

I am actually looking into this right now. No firm conclusions as of yet, but 50 little Ricardos, that is no net effect of state spending cuts, looks to be winning out.

First Kevin takes a step closer to the dark side

I always kind of wonder what these guys are thinking when they do such an obvious and public U-turn. Do they think no one is going to catch them? Or do they not really care because they don’t think the public really cares?

I think it used to be the former, but has lately become mostly the latter. Back in the day, I remember a lot of people saying that it was getting harder for politicians to shade their positions — either over time or for different audiences — because everything was now on video and the internet made it so easy to catch inconsistencies. But that’s turned out not to really be true. Unless you’re in the middle of a high-profile political campaign, it turns out you just need to be really brazen about your flip-flops. Sure, sites like ThinkProgress or Politifact with catch you, and the first few times that happens maybe you’re a little worried about what’s going to happen. But then it dawns on you: nothing is going to happen.

Democratic Fundamentalism is a belief in the wondrous healing powers of mass apathy.

I’d also like to uncritically quote from this Will Wilkinson post because it confirms all of my biases and I face essentially no cost from being wrong.

So why did Democrats suffer a whupping in November? As someone once said, it’s the economy, stupid. Again and again political scientists find that macroeconomic variables drive electoral outcomes more than any other factors. The Democrats did about as badly as we should expect the majority party to do during a brutal recession. Nevertheless, humans have story-hungry minds that see agency and intention everywhere. It rains because the gods want it to rain, and Republicans seized the House because Rupert Murdoch and the Koch Brothers funneled a fortune into an astroturf movement that got out the conservative vote. But this is precisely the sort of story about the tea-party movement Messrs Ansolabahere and Snyder say the electoral data debunks

A few interesting intellectual questions, such as, why is it we are so focused on rankings? Yes, the Hansonites will immediately answer that status is everything, but a more nuanced view would be, at minimum, be more fun.

However, rather than getting into those issues I thought time would be better spent on completely self-indulgent navel gazing.

Palgrave ranks economics blogs based on what looks like an “impact score.” How much does each blog set the conversation. The score seems to be primarily driven by a rolling 90 day average of the number of different blogs linking to your blog. The say they add some secret sauce which seems to be related to whether or not people link the people that link you, just by judging by the rankings.

For quite a while the top spots have been relatively fixed.

Paul Krugman is almost always number 1 and by a wide margin.

The number 2 – 5 spots fluctuate but are usually in this order: Economix, Marginal Revolution, Econbrowser, Free Exchange.

This is interesting in and of itself. The top blog is a noble laureate and a celebrated columnist. The rest of the top five is dominated by two professor blogs and two super high status periodicals. The status rankings in the real world seem to pass right through to the blogosphere.

Remember this ranking is not based on readership, but on impact. I am sure lots of people read DealBook, but according to Palgrave, no other economics bloggers link to DealBook. They drive readers but they don’t drive the conversation.

The bottom half of the top ten is usually: Modeled Behavior, Democracy in America, Naked Capitalism, Worthwhile Canadian Initiative, and a floater who is often Interfluidity.

Yet recently, there seems to have been a bit of shake-up. Brad Delong jumped up into the fifth spot, while Marginal Revolution fell to 9th.

Is this a technical thing? It always seemed strange that Delong wasn’t top ranked. Likewise it seems strange that Econlog isn’t ranked higher.

Who has the inside track on what Palgrave Rankings really mean?

That is how one analyst describes the negotiations over the structure of the future mobile payment services industry. Here is the full quote, from a fascinating article in the New York Times on mobile payments:

“It all comes down to who gets paid and who makes money,” said Drew Sievers, chief executive of mFoundry, which makes mobile payment software for merchants and banks. “You have banks competing with carriers competing with Apple and Google, and it’s pretty much a goat rodeo until someone sorts it out.”

Another compares the U.S. situation to other global markets where mobile payments are already widespread:

“Other global markets may have a single dominant mobile carrier, or a small number of banks, or a strong central bank,” said Beth Robertson, director of payments research at Javelin Strategy and Research. “And this has made it easier for them to reconcile a model.”

One way to streamline the negotiations would be to allow non-banks to become payment processors and banks.

Kevin Drum writes

Felix isn’t happy about this: "What we don’t want is a world where most companies are owned by a small group of global plutocrats, living off the labor of the rest of us. Much better that as many Americans as possible share in the prosperity of the country as a whole by being able to invest in the stock market." Agreed — but like Felix, I don’t have any bright solutions to this. And who knows? Maybe this is just the flavor of the day on Wall Street and the public stock market will make a comeback shortly. But the overall story of the past couple of decades has been the steady funneling of all the richest investment opportunities to a smaller and smaller class of the super rich, and this trend fits right in. It’s a problem worth thinking about.

The idea that all of the good investing will be eaten up by insiders with no way for outsiders to get a piece of the actions seems doesn’t seem right to me. It could come about from very stringent government regulation but outside of that my spidey sense is telling me that its unlikely.

The problem is this. Ok, I can make a lot of money as a rich insider getting in on Facebook. But, I can always make more money by leveraging the savings of other folks.

The question is how to get access to their savings. In the old old days people could drop their savings off at the bank and then the bank could go bananas. It could invest in everything from crop futures to perpetual motion. Needless to say this didn’t always work out as planned.

So more or less, we have corralled folks into tighter and tighter opportunities. New regulations of public companies might even be squeezing the public out of the direct ownership game altogether. Yet, there is always lots of more money to be made in leverage. Someone will find a way. Money clubs of some sort.

Maybe you could swing a deal where the ordinary investor like Kevin gets some fraction of the current receipts of a hedge fund, in return he makes them the beneficiary of his life insurance policy and then the hedge fund goes out and issues bonds backed by those benefits. Then the hedge fund uses the bond proceeds to invest in private ventures.

I just don’t see how any public or private system of controls can stop people from finding someway to get common money into the big game.

I mentioned yesterday that Duopoly in and of itself isn’t a problem. I want to dig deeper into that.

Going back to Lowrey’s original piece

Granted, Verizon and Sprint could enter into a price war with AT&T, much to the benefit of the average smartphone user on the street. Low-cost carriers like Leap and MetroPCS could chip away at the big companies’ business. But it seems unlikely to change the dynamics for the average consumer. Wireless is a resource-intensive business with serious barriers to entry, making it hard for small and local companies to compete at a national level.

Another way you might say this is that providing the services that consumers want is expensive. You sometimes here the complaint that wireless service is too expensive. Though, I think small low cost carriers do serve a to fill in that niche.

However, an equally pressing complaint is that the service sucks. Its not expansive enough, its not fast enough, I still have to have both a cable line and wireless service to get decent internet.

These are the kinds of problems that big companies can solve and they may in fact need to charge higher prices on a larger customer base to do it.

The primary concern with allowing a full monopoly is that is will actually reduce service.

Private companies, even monopolies, can’t force you to buy things. What they can do is offer crappy services or bloated packages that you wouldn’t want to buy if you had a reasonable choice. In some cases they can scale back service provision all together. This allows them to target their price at only a subset of the population, which indeed can bear higher prices.

However, this is precisely why any competition matters. For monopoly to work you have to restrict the customers options. Another competitor, even one other competitor, will then have the opportunity to take advantage of that.