You are currently browsing the monthly archive for March 2012.

PCE moved forward rapidly in Feb, no doubt raising tracking forecasts for Q1GDP. Importantly, it seems that while the decline in energy consumption has slowed, it has not reversed.

Regardless of what happens with the weather we should expect the official measures of energy consumption to turn north hard as the winter passes. In short, low heating during the winter cut deeply into consumer spending measures.

However, as we pass into the Spring the seasonal adjustment will except heating expenses to fall away anyway, so it will no longer count against consumer spending estimates. This will be reflected as boom.

Consider three leading explanations for the current weak economic conditions. First, a new paper from James Stock and Mark Watson identifies demographic shifts as an important determinant of poor current economic conditions, and a likely problem going forward:

…barring a new increase in female labor force participation or a significant increase in the growth rate of the population, these demographic factors point towards a further decline in trend growth of employment and hours in the coming decades. Applying this demographic view to recessions and recoveries suggests that the future recessions with historically typical cyclical behavior will have steeper declines and slower recoveries in output and employment.

Second, as Karl has argued, the economy is waiting for “the kick” of an increase in sales of durables like housing and autos. Third, you have low house prices in holding back the economy by weakening household balance sheets.

My question is this: do not all of these factors point towards more immigration to drive both a recovery now and a recovery from the decline in the long term economic trends? In The Great Stagnation, Tyler Cowen identified lots of immigration as one of the three main kinds of low hanging fruit that helped drive our earlier growth:

“In a figurative sense, the American economy has enjoyed lots of low-hanging fruit since at least the seventeenth century, whether it be free land, lots of immigrant labor, or powerful new technologies. Yet during the last forty years, that low-hanging fruit started disappearing, and we started pretending it was still there.”

But this low hanging fruit has not gone away. We have simply stopped grabbing it.

I find Shanker Blog’s Matt Di Carlo to be a reliable and very fair minded source for education research coverage despite coming from a somewhat different part of the ideological spectrum than I do on education reform. He has an assessment of the literature on TFA that I recommend. Although I don’t know this area of research very well, his discussion reflects my general impression. Here is how he summarizes:

One can quibble endlessly over the methodological details (and I’m all for that), and this area is still underdeveloped, but a fair summary of these papers is that TFA teachers are no more or less effective than comparable peers in terms of reading tests, and sometimes but not always more effective in math (the differences, whether positive or negative, tend to be small and/or only surface after 2-3 years). Overall, the evidence thus far suggests that TFA teachers perform comparably, at least in terms of test-based outcomes.

I also Matt is correct to look to the meta lessons about TFA and teachers in general, but I disagree somewhat about the meta lesson. He says:

But, to me, one of the big, underdiscussed lessons of TFA is less about the program itself than what the test-based empirical research on its corps members suggests about the larger issue of teacher recruitment. Namely, it indicates that “talent” as typically gauged in the private sector may not make much of a difference in the classroom, at least not by itself.

In contrast, I would say the lesson from TFA is that “talent” as typically gauged in the private sector makes as much of a difference as an entire four year teaching education does. If talent didn’t matter much, then you could give all teachers five weeks of training instead of four year educations and the outcomes would be comparable to what we are seeing now. Either talent doesn’t matter much or going to college for four years doesn’t matter much, in either case one is about equal to the other on average.

One thing this lesson implies to me about policy is we should think about how we can combine the most important aspects of the four teacher year education and boil it down to something more than five weeks and less than four years in order to make it easier to recruit people with TFA level talent into teaching. We should be experimenting more with alternative credentialing regimes for teachers.

ADDENDUM: In response to BSEconomist’s comment let me clarify. The evidence shows a lot of ability is worth about as much as a full teaching education. Yet we only allow two choices: a lot of ability with very little education (TFA), or a full education. We should allow a wider variety of substitution of ability for training instead of just all or almost none.

There seems to be some disconnect or bit of talking past one another on the issue of a housing recovery.

There are people in the Recovery Winter camp, like myself, who argue that the upturn in housing will contribute to sustained growth in the United States, baring major unforeseen shocks. That is, unless something identifiably contractionary happens we should expect growth to become more solid, with fewer disappointments and a steady path back towards our long run trajectory. In short, a recovery.

However, I am receiving a steady stream of comments noting the continued downward movement in home prices along with evidence that the uptick in new home sales and starts at the beginning of this year was a fluke.

So, to be clear, I don’t think there is any reason why we should expect strongly rising single family home prices in the near future. Nor, is my baseline assumption that we will see a strong increase in single family construction. The upturn at the beginning of this year was surprising to me as well.

In contrast, my thesis is first that single family construction will not fall any further. Currently new single family homes built-for-sale are running slightly behind new single family home sales. Inventory is at record lows and declining. Thus even with continued weakness in the existing home market we are not likely to see significant declines in new single family home construction.

This is in large part because new single family home construction is close to or outright dominated now by custom home construction. That is homes built by owner or built by contractor for a specific owner. There is no substitute for a custom built single family home and there is no reason to expect that people in this market are going to be doing worse economically. So, we think those builds are safe.

In contrast the baseline scenario involves a pick-up in multifamily construction as rents rise. At core the reasoning is that a breakdown in the mortgage market and/or folks desire to invest in single family homes does not change the need for housing. Currently America’s population growth is well outstripping its housing stock so that we have an abnormally large number of people per household and an abnormally small number of households.

Barring a large cultural change – which is possible – this will mean a steady increase in the demand for rental housing. We have seen this as rents are currently rising quite rapidly and reports from apartment owners show what are approaching record low vacancies.

This makes constructing apartments a great value proposition.

Now, lots of people point out that multifamily is a small part of the overall housing market. This is true but two things:

First, the small size of multifamily is a result of a 20+ year expansion of single family homes. Go back to the 70s and 80s and multifamily construction was on par with single family.

Second, for growth what matters is not the level but the absolute change. If multifamily went from its current pace of roughly 200K units a year to a pace of 800K units a year that would constitute massive growth, even though it would be well shy of the record pace that single family construction hit during the boom.

A residential industry that was pumping out 800Kmultifamily units along with roughly 400K single family units a year would also be in a robust recovery, with rapidly declining unemployment among construction workers.

This scenario, in which new home construction comes to be dominated by multifamily built-to-rent units does not require the single family housing market to normalize anytime soon. Indeed, it predicated on the assumption that the single family home market will not normalize soon.

If the single family home market does normalize it will put a dent in the multifamily market. I suspect that part of the reason multifamily isn’t accelerating any faster is concern that the single family market will repair itself ahead of schedule and knee-cap rising rents.

You just can’t beat this closing, in my mind’s eye it was complete with a mic drop and Scott walking off stage right.

Monetary policy should always be set in such a way as to produce on-target expected NGDP growth. That’s the Lars Svensson principle. If you do that, there’s no room for fiscal stimulus, even if the economy is currently depressed. With a central bank that targets expected NGDP growth along a 5% growth path, you are in a classical world. Spending has opportunity costs. Unemployment compensation discourages work. Saving boosts investment. Protectionism is destructive. And so on. That’s the policy we should be teaching our grad students. The optimal monetary policy. Not a policy mix that only has a prayer of making sense in countries where the central bank is even more stupid and corrupt than the Congress. As far as I can tell, those countries don’t exist.

A cursory look at personal income statistics shows that the biggest drag on personal income right now is the decline in transfer payment from the government. At first this seems natural as the economy is recovering and automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance work in both directions. They slow the descent into recession but as they roll off they also slow the recovery.

Yet, the recent numbers were to big to explained by unemployment insurance alone. It turns out government health care spending is dropping by unprecedented amounts.

Below are year over year declines in transfer payments

The blue line is Medicaid which is now outpacing Unemployment insurance in terms of absolute year-over-year spending reduction. The red line is Medicare, which is whose year-over-year spending is not quite in decline but appear poised to make declines in the coming months.

This may be why the fundamentals in health care look surprisingly weak. Job gains have slowed as well as capital expenditure.

Just a quick shot. One growing point of tension that I that has both semantic and substantive difficulties is whether or not we regard the situation in the mortgage markets as “structural.”

Clearly the health of the mortgage market is strongly influenced both the business cycle and likely by monetary accommodation directly. It also is dynamic in that we don’t expect things to last.

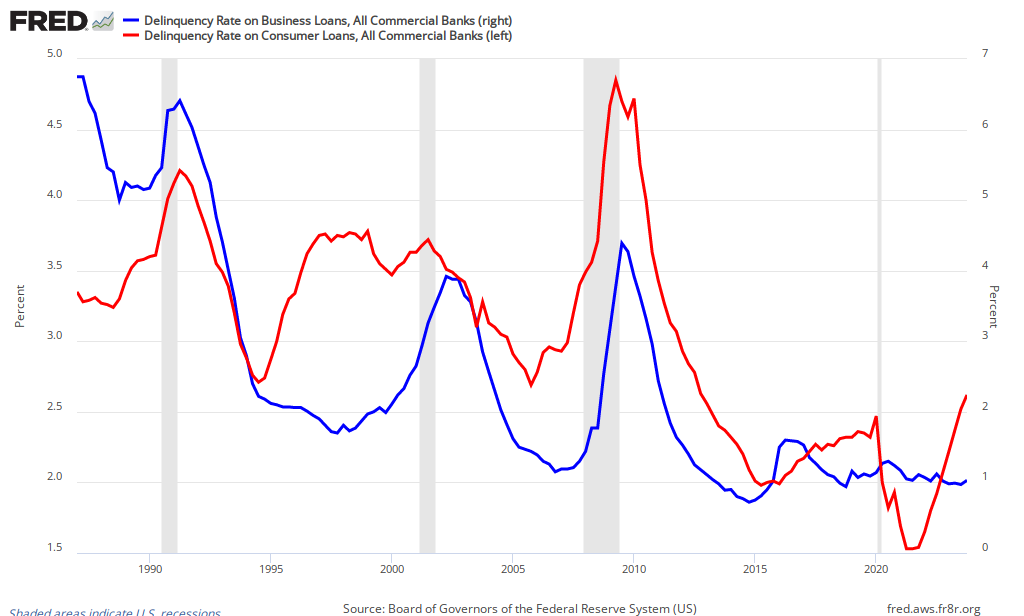

At the same time its also clear that it changes how monetary policy affects the economy. To illustrate, the problems in the mortgage market are well known but look at commercial banking outside of the mortgage market.

A rapid return not just to normalization but to conditions that are almost as good as it gets.

This seems to be the theme building in Federal Reserve speeches and communication. Ben Bernanke today.

To sum up: A wide range of indicators suggests that the job market has been improving, which is a welcome development indeed. Still, conditions remain far from normal, as shown, for example, by the high level of long-term unemployment and the fact that jobs and hours worked remain well below pre-crisis peaks, even without adjusting for growth in the labor force. Moreover, we cannot yet be sure that the recent pace of improvement in the labor market will be sustained. Notably, an examination of recent deviations from Okun’s law suggests that the recent decline in the unemployment rate may reflect, at least in part, a reversal of the unusually large layoffs that occurred during late 2008 and over 2009. To the extent that this reversal has been completed, further significant improvements in the unemployment rate will likely require a more-rapid expansion of production and demand from consumers and businesses, a process that can be supported by continued accommodative policies.

Rate are improving, but “conditions remain far from normal” in the level.

This links well with “economic conditions are likely to warrant an exceptionally low level for the Federal Funds rate”

We are beginning to see a strong implicit recognition that the relevant economic conditions are not the growth rates of real variables but the level of those variables, particularly employment.

Fed officials appear unwilling at this point to make similar statements about the price level, though we have seem some significant table-setting by Charles Evans in that regard.

Though I would generally regard this as a slow and steady move to shift expectations, it could also be regarded as “Odyssean” guidance, in that as the Fed takes more and more implicit responsibility for the level of employment it is providing ammunition to its dovish critics.

This in turn changes the Fed’s loss function so that an attempt to raise rates early is more difficult.

I should note the dynamics of a body that has some but limited tools to alter its own loss function are fascinating in-and-of-themselves.

People have complained that Amazon factory warehouse jobs are marked by poor conditions and low pay, but this may be less of a problem in the not to distant future. Amazon has acquired robots maker Kiva systems for $775 million and they are planning on replacing warehouse workers with autonomous robots. The New York Times reports:

…Kiva Systems’ orange robots are designed to move around warehouses and stock shelves.

Or, as the company says on its Web site, using “hundreds of autonomous mobile robots,” Kiva Systems “enables extremely fast cycle times with reduced labor requirements.”

In other words, these robots will most likely replace human workers in Amazon’s warehouses.

Despite the ugly conditions that can reportedly occur at Amazon warehouses, I don’t think the workers will be better off when these jobs are replaced by robots. The article also reports on the general trend of Robots Are Stealing Our Jobs:

Robots have been in factories for decades. But increasingly we will see them out in the open. Already little ones — toys, really — sweep floors. But they are getting better at doing what we do. Soon, if Google’s efforts to create driverless cars are successful, cab drivers, cross-country truckers and even ambulance drivers could be out of a job, replaced by a computer in the driver’s seat.

In the video below you can see Kiva robots perform The Nutcracker.

Tyler Cowen discusses the general implications of runs on the new (shadow) banking system. Though this point leads directly into something that I have been thinking about

Another feature of this new order is that more and more financial transactions will be collateralized with the safest securities possible: United States Treasuries. Demand for them will remain high, and low borrowing costs will ease our fiscal problems. Still, the resulting low rates of return serve as a tax on safe savings, encourage a risky quest for yield and redistribute resources to government borrowing and spending. It isn’t healthy for the private sector when investors are so obsessed with holding wealth in the form of safe governmental guarantees.

Its actually not clear to me that demand will remain high, in the sense that the term spread will not reassert itself. To explain a bit more:

The interest rate on T-Bills is simply whatever the Fed wants it to be. T-Bills and excess bank reserves are essentially interchangeable. In normal times the value of excess reserves is the Fed Funds rate. Today it is the Interest on Reserves rate. However, both of those are essentially controlled by the Federal Reserve.

If we lived in a world with zero risk then one would expect the interest rate on 10 year Treasury bonds to simply be the weighted average of the interest rate on T-Bills for the next ten years.

However, there is risk so, investors (a) have to guess what that interest rate will be and (b) demand a premium for the risk that they are wrong. This is the term premium and its why interest rates on long term government bonds are persistently higher than short term government treasury bills.

To the extent that expectations or risk appetite in the bond market exert direct influence on US Treasury interest rates, it is through the term premium.

Right now the term premium is extremely low, indeed one would guess that it is negative. The interest rate on a 30 year government bond is only 3.3%.

While its possible that the interest rate on T-Bills averages only 3.3% over the next 30 years this is – hopefully – extremely unlikely. It implies that nominal GDP growth will average 3.3% over the next 30 years, as the Fed must ultimately align interest rates with nominal growth rates or the economy will persistently overheat or stagnate.

The more likely explanation is that the demand for safe liquid assets is so high that investors are willing to accept a negative term premium.

Will this continue?

The answer is almost assuredly, no.

This implies that long term interest rates on government debt is likely to rise and that conversely the value of long term government debt will fall.

US Government debt is in a bubble.

I am coming to believe that bubbles are a persistent feature of the modern global economy and extend from the fact that the world is aging. As this continues the bubbles will likely only get larger and larger.

The simple reason is that as individuals pass into middle age they attempt to increase their savings. One way to do this by loaning or renting resources to the next generation. However, as the population ages opportunities to do this are more and more rare.

This implies that savings can only take place through capital deepening. In essence this means more investment per worker. This expansion in investment per worker causes some types of capital to liquefy. That is, existing pieces of capital can readily find a buyer at fundamental values.

Yet, once capital liquifies it begins to earn a liquidity premium – like the one earned by US government debt now. This, in turn, drives the market price on the capital even higher and we enter a bubble.

In practice, the capital object itself doesn’t get moved around but a financial instrument entitling someone to the rents from the use of the capital or a debt secured by the capital. However, the effect is the same. The financial instrument becomes liquid, starts to earn a liquidity premium and then goes into a bubble.

My growing sense is that this process has been repeated over and over again since the late 1980s. First, in Japan. Then in Korea and South East Asia. Then in the US tech industry. Then in the developed world’s housing markets. Now in US and UK government debt.

Moreover, there is no obvious way to stop this from happening. On first thought it would seem that deflation could prevent this by causing cash to earn a positive rate of return. This basically just ratchets up the money bubble.

However, without negative nominal interest rates this worsens the ultimate problem of expanding the capital stock because it essentially subsidizes money as a store of value against capital.

So, I don’t know that there is a clear way to stop this from happening.

One thing I have noticed is that just based on my wading through economic cycle data over the years I have tended do discount the notion of economic confidence as irrelevant and concepts like multiple-equilbria-in-macroeconomic-aggregates as completely unlike anything we observe in the real world.

Yet, my fellow economists, particularly older ones take the notions quite seriously.

Michael Forli suggests that times may have changed

A final, somewhat technical, implication is that the conditions for self-fulfilling prophesies in the macroeconomy may no longer exist. The idea that there could exist virtuous/vicious circles between real economic outcomes and confidence (or asset prices, effectively the same thing) was first formally advanced by David Cass and Carl Shell. They referred to these virtuous/vicious circles as “sunspot equilibria;” George Soros dubbed the property “reflexivity.” Subsequent applied macroeconomists appealed to the procyclicality of productivity as evidence of the type of increasing returns to production sufficient to generate confidence feedback loops. If labor is no longer a quasi-fixed factor of production this may eliminate one type of non-convexity in production, thereby reducing the likelihood that the economy has multiple equilibria and is subject to self-fulfilling prophecies. While it is hard to say much definitively, it is interesting to observe that over the last two years the economy has been subject to large swings in investor sentiment and asset prices, and yet actual growth outcomes have been remarkably stable.

Dave Altig offers the following

If you try, it isn’t too hard to see in this chart a picture of a labor market that is very close to “normalized,” excepting a few sectors that are experiencing longer-term structural issues. First, most sectors—that is, most of the bubbles in the chart—lie above the horizontal zero axis, meaning that they are now in positive growth territory for this recovery. Second, most sector bubbles are aligning along the 45-degree line, meaning jobs in these areas are expanding (or in the case of the information sector, contracting) at about the same pace as they were before the “Great Recession.” Third, the exceptions are exactly what we would expect—employment in the construction, financial activities, and government sectors continues to fall, and the manufacturing sector (a job-shedder for quite some time) is growing slightly

First, a clarification. Its not immediately clear from Altig’s post but the chart indicates that employment in non-motor vehicle manufacturing is expanding far, far faster than would be expected given the last recovery.

This is important for thinking about any kind of structural story you might be inclined to tell. Manufacturing employment had been falling rapidly for roughly 15 years and then suddenly stopped falling in the wake of this recession and started growing very slowly.

This may be the structural shift that folks are looking for but its important to note that this is basically a “reshoring” shift. Although, its not so much reshoring as a rapid slowdown in offshoring combined with growing underlying demand.

In addition, the dynamics of the dot-com recession were very different. Though it felt mild to most folks and the employment rate only barely peaked above 6% it was actually slightly more harsh for non-financial corporate profit growth.

Here are non-financial corporate profits on a log scale. You can see the divot from Dot-Com was proportionately the largest on record.

That recession behaved in many ways like what you would expect if you were experiencing a demographic slowdown. Capital took a huge beating. Employment growth was slow and unsteady, but unemployment was mild.

Lets look at private sector employment in the two recoveries

The bottom of Dot-Com was long and drawn-out while the Great Recession was sharp, returning almost immediately to growth rate during the last recovery.

If we look at compounded annual rates of growth, private sector payroll growth during the Great Recession return to above long-run trend (2%) sooner than either of the last two recessions, despite being deeper.

So private sector employment growth has been quite strong. GDP, less so.

There has been a divergence in Okun’s law, even when looking at long run patterns

Though notice the deviation is even more pronounced using a nominal version of the law, suggesting that nominal spending growth exceeding maximum production growth is not yet the issue

Based on both the growth in payrolls and the decline in unemployment historical patterns would lead us to expect real GDP growth of around 4% and nominal GDP growth of around 6.5 – 7%.

I think the strongest clue in explaining this discrepancy comes from looking at non-durable goods output.

The big unexpected surge in employment is in manufacturing ex-motor vehicles. Though again its not so much job gains as the absence of job losses. Motor vehicles make up a large part of the durable goods sector, so we can get a proxy for non-vehicle manufacturing by looking a non-durable goods.

Despite the above average employment growth – which is to say the absence of employment shrinkage – production in non-durable goods is way down and indeed declining.

So the GDP discrepancy looks like it may be due to a sectoral shift and possibly the closing of opportunities to offshore portions of the non-durable supply chain.

In general I think looking to GDP introduces unnecessary opaqueness in the modern age. We have easy access to much finer data. In this case GDP would provide a potentially confusing measure of the state of the economy as compared to payroll growth or unemployment.

If it is the case that GDP growth is slowing because non-durable production is slowing despite rapidly increasing employment then it is likely that we will soon see increased investment in the sector boosting productivity and creating a following period where GDP rises faster than employment.

Not everyone will lose from climate change, or to put it another way, not everyone would gain from climate change mitigation policies. But a smart mitigation policy, like a carbon tax, creates more benefits overall than costs. Some people will see the benefits over gains as sufficient justification for mitigation policy, but others oppose such policies unless the redistributive effects of the policies are compensated for so that the change is a pareto improvement. With climate change this would be, for example, areas of the country where cheap gas prices or carbon based energy production are disproportionately important.

Not everyone will lose from protectionism, or to put it another way, not everyone would gain from free trade. But free trade creates more benefits overall than costs. Some people will see the benefits over gains as sufficient justification for free trade, but others oppose such policies unless the redistributive effects of the policies are compensated for so that the change is a pareto improvement. With free trade this would be, for example, areas of the country where manufacturing jobs that would be displaced by trade competition is disproportionately important.

I don’t think there will be much of a correlation between these positions, yet they use similar logic. How do people decide when redistribution effects of a policy change are sufficient to overcome the desirability of benefits exceeding costs? Is there something more than political allegiance going on here?

A counter-structural as well

How tight? Lets invert

Via Real Time Economics, a decidedly well crafted message

I am at the moment in a position that I’ve called essentially patient vigilance–meaning that I want to see how the economy evolves before drawing conclusions that more stimulus is needed and could actually have the effect where the benefits would outweigh the costs. I don’t rule it out.

By laying out the choice in this way Lockhart both loosens Fed policy and strengthens long term credibility. Essentially we see a re-weighting of the Fed’s loss function rather than an adjustment to its optimal rule or distribution in economic estimates.

Long time China correspondent Adam Minter has a good interview in Time Out Shanghai that anyone interested in labor standards in China should read. Here is how he answered a question about whether Foxconn’s labor standards need to be improved:

My expertise is not in high-tech manufacturing, but rather recycling facilities like scrap yards, and raw material processing facilities like aluminum smelters. I wouldn’t want to generalize either of those industries, but I can tell you that companies engaged in raw materials are far more dangerous, unhealthy, and unpleasant places to work than somewhere like Foxconn. Indeed, I can think of a range of industries that are more dangerous than Foxconn: textile dying, batttery manufacture, paper making, the list is endless.

The goal should not be raising the standards of Foxconn, but rather the much more difficult task of raising up China’s other industries to the level of a Foxconn. Responsibility for that, however, belongs to the various levels of the Chinese government, ultimately. I don’t think any amount of consciousness raising on the part of foreigners can make a bit of difference.

I don’t think Mike Daisey has had any impact on China’s labor situation, and I don’t expect his current troubles to have an impact either.

Binyamin Applebaum writes

The bleaker view – which remains, to be sure, the view of a distinct minority — is that the years before the recession were abnormally good, and that while the recession was abnormally bad, reality lies halfway in between.

The present situation, in other words, is about as good as it gets.

A paper that will be presented Thursday afternoon at a conference organized by the Brookings Institution is the latest contribution to this literature.

The paper, entitled “Disentangling the Channels of the 2007-2009 Recession,” will be posted on the general conference Web site Thursday afternoon.

I think this confuses strong GDP growth with a good economy. If the number of workers is shrinking in principle you could have an economy that felt great with low GDP growth and on the other side if the workforce was soaring then even a 4- 5% GDP growth rate will feel bad, as was the case in the late 70s.

By my reading Stock and Watson argue that the only thing inexplicable about this recession is the fact that there are more workers than expected. Demographic factors had been pushing down the employment growth rate but now there is a surprisingly large workforce.

Here is one thing to note:

The blue line is year over year job growth for those 55 and older. The red 24 – 54, what we would consider prime age.

Since, the dot-com bust net employment growth among those over 55 exceed that of those in their prime. This is not as a fraction of the population – this is total.

The only point where prime age workers even caught up was during the tail end of the construction boom.

During the Great Recession employment growth among those over 55 never went negative and is now growing at a record pace.

By contrast employment growth among those 24 – 55 was never positive (save for one month) until just recently.

One quick and dirty explanation would be that the Baby Boomers are not retiring as fast as expected and this had led both to extremely rapid growth in over 55 employment and to surprising labor market dynamics for younger workers who may have been expecting an easier job market than materialized.

Indeed, I wouldn’t push it this far but one could argue that this explains both the size of the housing bust and the business investment boom.

The business capital-to-labor ratio turned out to be lower than everyone expected when the boomers didn’t retire. This put downward pressure on the marginal productivity of labor which manifested itself as a tight job market for young workers. This in turn meant lower household formation and lower housing demand.

On the other side, however, it meant an increase in demand for business capital to complement an unexpectedly large workforce.

The ongoing debate about Apple’s supply chain in China has me wanting to put down a couple of quick thoughts on corporations and whether they should, to put it broadly, promote laws and standards around the world. This isn’t an attempted knockout punch to any position, and while I am often a critic of regulations, and will be here in some places, this is just as much of a rebuttal to Milton Friedman’s argument that the only social obligation of business is to maximize shareholder profits.

In many developing nations, the legal system functions poorly, and international corporations are often more capable of enforcing efficient laws throughout their supply chain than anyone else. This can be, to some extent, due to pressure from U.S and other western customers to “behave ethically”. This can be good both because it enforces efficient and desirable laws, and because getting a supply chain to be able to conform to any standards, whether they are quality, ethical, or efficiency standards, is a necessary step in moving up the manufacturing value chain. One example of this would be how Walmart is able to enforce environmental laws that are likely closer to efficient than what the local governments enforces. Pollution can do a lot of costly and unfortunate damage to health and the environment in developing areas with weak rule of law.

Another benefit of corporation enforced standards, which applies to environmental, labor, and other kinds, is that corporations are more likely to find the least cost ways to comply. A corporation with a broad goal can be more efficient than specific government mandates.

Friedman argued that shareholders, workers, managers, or CEOs can contribute to social causes with their own money outside of the corporation. But stakeholders of Walmart can get far higher social return for $1 spent within the company than outside it. And as Friedman agrees in his essay, if a manager loses money for a corporation by behaving with social responsibility, free markets will ensure that it comes out of their wages. So if it is CEOs making the decision to sacrifice $1 of profits for $10 of social returns, then the corporation will take that $1 back through lower compensation, creating $9 of value. But if a CEO chooses to operate outside the corporation, it may cost him $9 to get the same $10 of return, creating only $1 of net value. Consider the example of a CEO who refuses to sign off on $1 million in pollution to save the company $100k. In contrast, if the CEO allows the spill to happen and then tries to clean it up with his own money it will probably cost closer to $1 million than $100k.

This argument requires efficient markets for executive wages, and an obligation to not hurt society to save yourself a fraction of the cost. Nothing too radical. Importantly, such spending will often be far more profit maximizing than is assumed, so the $1 of nominal cost to the company is often much less when private returns, for example marketing value, are considered.

Despite these positive aspects of corporate standards and social responsibility, when these corporations are responding to the demands of U.S. and other western customers there is a downside risk that they will enforce standards in accordance with our preferences that are less in accord with the citizens of the affected countries than if they simply profit maximized. This is a real concern with respect to labor laws. People tend to have the misconception here that our standards of living are disproportionately a result of our labor laws, and that the way our jobs became safer, healthier, and higher paid is mostly about regulation instead of mostly about economic growth. People also tend to believe that we have “exported” bad jobs to China, rather than understanding that as far as manufacturing jobs go in China, working for foreign corporations, including Apple, are above average quality. If American companies were very responsive to consumer demands, labor laws in China would very likely be far too strict.

Even when the labor laws come from the developing countries themselves than can be problematic. Here is what Tim Culpan, who has been covering Foxconn for 10 years, had to say about what he sees there:

In our reporting, as “Inside Foxconn” detailed, we found a group of workers who have complaints, but complaints not starkly different from those of workers in any other company. The biggest gripe, which surprised us somewhat, is that they don’t get enough overtime. They wanted to work more, to get more money.

Why would these young workers want to work what look to us like extreme amounts of overtime? Culpan explains:

Rather than forced labor and sweatshop conditions, workers told of homesickness and the desire to earn more money-two impulses that seemed to drive each other for workers planning to go home once they’d earned enough.

If labor laws mean that workers can’t do as much overtime as they’d like, one of the unintended consequences of this looks like it could be to force these workers to stay at the factories for a longer period of time before they earn enough to go home. Should labor laws, either domestic or imposed by foreign corporations, prevent workers from taking on as many hours as they are willing?

Maybe, I suppose. These are young workers after all, and maybe there is a clear level of hours beyond which health is clearly at risk. But you have to know an awful lot about the workers, the factories, the local culture, and a lot of things that American consumers probably don’t have a very good grasp of. Furthermore, the journalists who have spent years in China and know the most, like Adam Minter and Tom Culpan, seem to have the least criticism for Foxconn and the manufacturing in China for international corporations. I am reminded of what Freddie DeBoer wrote about Libyan intervention:

What interventionists ask of us, constantly, is to be so informed, wise, judicious, and discriminating that we can understand the tangled morass of practical politics, in countries that are thousands of miles from our shores, with cultures that are almost entirely alien to ours, with populaces that don’t speak our same native tongue. Feel comfortable with that? I assume that I know a lot more about Egypt or Yemen or Libya than the average American– I would suggest that the average American almost certainly couldn’t find these countries on a map, tell you what languages they speak in those countries, perhaps even on which continents they are found– but the idea that I can have an informed opinion about the internal politics of these countries is absurd…

…A colossal, almost impossible arrogance underpins all interventionist logic. Beneath it all is a preening, self-satisfied belief in the interventionist’s own brilliance and understanding. So I ask you, as an individual reader– are you that wise? Are you that righteous? You understand so much? When was the last time you read a Libyan newspaper? Talked at length with a Libyan? A year ago, what did you know of Libya and its internal struggles?

Labor laws aren’t war, and Apple critics aren’t Neocons. I don’t want to take this analogy too far. But some of the criticism Freddie makes here apply to arguments about demanding companies in China comply with U.S. labor standards. You can counter that all that is being asked is that the companies comply with Chinese laws, but this is not always the case. Furthermore, the decision to not enforce a law is also a legitimate decision a nation may choose to make. And to the extent workers wish to not comply with the laws, we are asking companies to override their wishes. Just as we should have humility about our ability to know what is best for another country, we should have humility about a country’s ability to know what is best for workers and their employers.

Freddie elsewhere wonders:

Would Ira Glass ever allow his children, when grown, to work 60 hours a week? In those factories? In those conditions? Of course not.

But these aren’t Ira’s children, and he shouldn’t act as if they are. Neither Freddie, nor Ira, nor I really knows what Chinese workers want. Even within this country, let alone across the world, people have vastly different preferences with regards to how many hours they want to work, what risks they are willing to take for what compensation, and all of that. I don’t think Ira would allow his children to be crab fisherman in the United States either, but that does not mean we want these jobs to be regulated until they are safe enough and well paid enough that Ira Glass would send his children to work there, or until they are regulated out of existence, which in many cases are the same thing.

Scott writes

I certainly approve of the cash dispersion, as the principle-agent problem suggests that highly successful corporations will be tempted to waste their cash hoards on boondoggle investments. So it may be good for the economy. But I don’t see how it does much for the zero bound problem. At least I don’t see any first order effects. If Apple saves less I’d expect the recipients of this money to increase their saving my an equal amount . . . Those rich enough to own individual shares often have brokerage accounts where the dividends automatically spill into a money market mutual fund. If at the end of the month you have a tiny bit more in the MMMF, and a tiny bit less in Apple stock, but the total of the all assets remains exactly at say, $857,000, are you really going to spend more on consumption? I don’t see it.

I don’t think the key issue is consumption per se but whether money used to buy Treasuries is equivalent to money used to buy MMMF shares. I think the answer right now is no.

Right now the yield on T-Bills, the Interest on Reserve Rate and the overnight rate at MMMFs are not moving in total sync.

T-Bill yields are near zero, IOR is at 0.5% and MMMF rates have been on a glide path downward and have recently crossed the IOR rate.

One conclusion – that I tend to support right now – is that these products do not have equivalent envelopes, so that adjusting balances between them does have real liquidity effects. In particular, the marginal dollar on a reserve balance sheet will simply be held as excess reserves while the marginal dollar in an MMMF will be reverse repo-ed to a private sector counterparty using non-treasury collateral.

In addition, though I am still working this out in my head, I think an unstated objective of potential “sterilized” QE would be to eliminate this effect by making the Fed the marginal destination for MMMF inflows.

At first you could hear the sound of the neutron counter, clickety-clack, clickety-clack. Then the clicks came more and more rapidly, and after a while they began to merge into a roar; the counter couldn’t follow anymore. That was the moment to switch to the chart recorder. But when the switch was made,everyone watched in the sudden silence the mounting deflection of the recorder’s pen. It was an awesome silence. Everyone realized the significance of that switch; we were in the high intensity regime and the counters were unable to cope with the situation anymore. Again and again, the scale of the recorder had to be changed to accommodate the neutron intensity which was increasing more and more rapidly.Suddenly Fermi raised his hand. “The pile has gone critical,” he announced. No one present had any doubt about it.

Slightly more prosaically, from Reuters

One of the most bullish investors is Carrington Capital Management, which has teamed up with Los Angeles-based OakTree Capital. They have created a $450 million fund to buy foreclosed homes in bulk and rent them out.

In a marketing document for one of its funds, Carrington claims that without using leverage or borrowed money it can generate an annual yield of 7 percent from rental income alone. Its long-term strategy is to package the fund into a publicly traded real estate investment trust. If that strategy is successful, Carrington projects investors can see an internal rate of return of 25 percent over three years.

New York Fed President Dudley said recently

While these developments are certainly encouraging, it is far too soon to conclude that we are out of the woods. To begin with, the economic data looked brighter at this point in 2010 and again in 2011, only to fade as we got into the second and third quarters of those years.1 Moreover, the United States has experienced unusually mild weather over the past few months, with the number of heating degree days in January and February about 17 percent below the average of the preceding five years. While this reduces the amount that households and businesses must spend for heating, I suspect that it temporarily boosts economic activity overall. For example, the mild weather is certainly conducive to higher than normal levels of construction activity, and we did see a surge in hours worked in that sector over the past few months.

Dudley didn’t make this fully clear but the direct effect of less home heating is that Personal Consumption Expenditures fall – this is where utility bills go in GDP – and that Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization fall as utility output counts towards these totals.

His suggestion is that this is overwhelmed by increases in residential construction and other factors, so that the net effect of mild weather is larger measured economic output.

I am not actually sure which way it goes because the drops in the utility portion of PCE were dramatic and the increases in construction activity were not that far off what I would have guessed otherwise. Single Family starts were surprisingly strong, but builder confidence was surprisingly strong as well.

Mutli-family seems to be evolving more or less as expected maybe a little slower.

In any case, I do want to make the point that emphasizing these factors is in-and-of-itself counterproductive for the dovish Fed policy that Dudley likely supports.

It may seem that downplaying the economy’s strength supports a more dovish policy stance. However, that is not what is important to communicate. What’s important to communicate is the Fed’s reaction function and emphasizing a weak economy makes it harder to emphasize a loose reaction function.

Why?

Well imagine if Dudley said the economy is booming, housing starts are moving in the right direction and unemployment is coming down. Nonetheless, I think the low levels of total employment in the economy are likely to warrant an exceptionally low level for the federal funds rate until at least late 2014.

This tells you that look, even if the economy is growing strongly the New York Fed President still doesn’t want to raise rates for a while. So, that means my estimation of the path of the funds rate should fall in all cases.

I shouldn’t respond to exceptionally good data by thinking the Fed will tighten and I should respond to weak data by thinking the Fed will stay loose longer.

That market participants come to believe this is loosening of Fed policy.

However, if you imply that the only reason you want loose policy is because you expect the economy to do poorly then that could in fact tighten Fed policy.

Now

Perhaps, Dudley is entering into higher dimensional chess where he is attempting to tilt the FOMC towards a more accommodative stance and signal to the market that the FOMC is out of touch with reality and overly pessimistic.

I am extremely wary of these types of moves and think you can easily overestimate the sophistication of market participants.

Lastly

It could simply be the case that this is Dudley view and he is sticking to it. In which case I can’t fault him for that. It is simply unfortunate that he is not in a position to stake out a more dovish stance.

From the Washington Post

As calculated by federal statisticians, the productivity growth of U.S. factories has seemed quite impressive. Between 1991 and 2011, productivity more than doubled, meaning that a single worker today produces what two did 20 years ago, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics figures.

Except that it doesn’t mean this. And, unless there is just some weird co-incidence, it never has and never will mean this.

It means the ratio of output-to-workers has doubled, which could be achieved by lots of means – not least of which is simply changes in the composition of output.

So, if people were consuming mostly processed food which required a lot of labor per output, but over time the consumption share moved to laptops which require much less labor per unit of output then productivity would rise, even though nothing at all has happened to any manufacturing process.

Indeed, this is possible even if labor productivity in each sector actually falls. Also, the reverse is true, labor productivity can fall even if the productivity in each sector rises.

This is in addition to the fact exploiting comparative advantage to ship US jobs overseas raising productivity and that innovation that raises the value of the output raises productivity.

Likewise if a cashier at a jewelry store rings up one $10,000 item an hour then he is more productive than a cashier at a grocery store who rings up 1000 $5 items an hour. This is despite the fact that by all appearances the cashier at the jewelry store is accomplishing less in the course of an hour.

This is because the statistics productivity is just not congruent with the common notion of being productive.

The piece goes on to discuss import price bias which would underestimate the total value of imported products

Critically, Houseman and others have shown that the price savings that U.S. factories have realized from outsourcing have incorrectly shown up as gains in U.S. output and productivity.

. . .

The federal statistical agencies, which have helped fund Houseman’s work, agree that the bias exists, though they say there might be other problems that are offsetting.

I don’t know for sure if this is what the agency heads were trying to communicate, but an important point is that while import price bias can produce granular statistics that do not measure what they claim to measure, they must do that at the expense of something else happening.

So, for example, if proper accounting shows that the real value of an IPad is 70% foreign rather than 50% foreign, then something has got to go the other way to explain how 50% of the revenue shows up in Apple’s bank account after supply chain costs.

Its not immediately clear what that thing is, but it has to be somewhere because by design these numbers all have to add up consistently.

Ultimately I really think the problem is that increasing productivity sounds like something that should make you feel good, but some of the results of the process make most people feel bad.

And, so the argument is really over: should we feel good or bad about this evolution of events.

Paul Krugman notes

Finally, it’s hard not to have the sense that when political types in this administration talk about appealing to “voters”, what they really mean is appealing to self-proclaimed centrist pundits who claim to have their fingers on the pulse of independent voters. Aside from the fact that they don’t — that the complicated psychodramas concocted by pundits exist only in their heads, not the heads of voters — experience shows that nothing Obama can do will satisfy these guys; they need, professionally, to maintain the pretense that both sides of the political divide are equally extreme.

Here is my question, though: to what extent are people even making this claim?

I grant this is a part of the verbage used by pundits, but if you said, “can you produce in the flesh even one person who has ever had the thought process you ascribe to independent voters” would they insist the answer is yes? Would they bet on it?

Or, is this just a giant rhetorical edifice that has been constructed over the years.

My sense is that people tell these stories because its fun to tell these stories and people read these stories because its fun to read the stories but no one in the entire loop is actually very concerned about whether or not the stories are true.

Apple announced this morning a major dividend program that is set to transfer profits to shareholders at a significant rate. From the looks of it starting at roughly $10 Billion per year. Though that is small relative to expected Apple profits, even I would admit that this is a huge initial commitment.

Obviously, I have been accusing Apple executives of hoarding cash in an attempt to protect their own interests and the long run survivability of the company rather than maximizing the return on equity of shareholders.

To add insult to injury, share price was down in the immediate wake of the announcement, which though anticipated by a few analysts cannot be regarded as anything other than a discrete jump in market expectations.

There is just no way at this point I can see a narrative in which my story was correct and Apple and the market responds in this manner together.

I will have an update as information becomes available but right now this looks like nothing less than Epic Defeat for my thesis.

I get the sense that one reply to the Mike Daisey scandal is that “well, he may not have seen what he says he saw, but those things are happening and well documented”. But Daisey did not just take the reality conveyed in other accurate reporting and pretend that he saw it with his own eyes. No, because the stories he tells aren’t just made up, they also fail to characterize the situation correctly. You can see this importantly in how widespread and obvious he makes underage workers at Foxconn look. Here is how Daisey reported it in the monologue portion used in This American Life:

And I say to her, you seem kind of young. How old are you? And she says, I’m 13. And I say, 13? That’s young. Is it hard to get work at Foxconn when you’re– and she says oh no. And her friends all agree, they don’t really check ages. I’m telling you … in my first two hours of my first day at that gate, I met workers who were 14 years old, 13 years old, 12. Do you really think Apple doesn’t know?

This is not just a story about Daisey meeting underaged workers, but a claim about how easy it is to find them. And as you can see in the transcript from the retraction episode of TAL, Daisey’s claims are in contrast to what his translator says:

Rob Schmitz: Do you remember meeting 12 year-old, 13 year-old, and 14 year-old workers here?

Cathy Lee: No, I don’t think so. Maybe we met a girl who looked like she was 13 years old, like that one, she looks really young.

Rob Schmitz: Is that something that you would remember?

Cathy Lee: I think that if she said she was 13 or 12, then I would be surprised. I would be very surprised. And I would remember for sure. But there is no such thing.

Ira (narrarating): She’d be surprised, because she says in the ten years she’s visited factories in Shenzhen, she’s hardly ever seen underage workers.

As TAL reports, Apple has been aggressive about underage workers and they are rare:

In fact, underage workers are sometimes caught working at Apple suppliers. Apple’s own audit says in 2010 when Daisey was in China, Apple found ten facilities where 91 underage workers were hired … but it’s widely acknowledged that Apple has been aggressive about underage workers, and they’re rare. That’s 91 workers out of hundred of thousands. Ira asked Mike about this on the This American Life broadcast, and he admitted it might be rare, but he stuck by his story

This is not consistent with anyone being able to walk up to Foxconn and within two hours be talking to underage workers. The story Daisey tells is one where Apple is negligent to an obvious and easily solved problem, whereas the facts TAL reports are of a company trying to stop underage workers and failing on relatively rare occasions. This kind of lie is not telling the story of the truth through a fictional narrative, but creating a fictional narrative that contradicts the bigger truth.

There are opposing narratives about the Apple, and Chinese labor and manufacturing. One sees the issue as black and white, simple, and easily solveable. Another sees it as a complex issue with no easy solutions, and that requires real tradeoffs. The former is how Mike Daisey tried to portray things, and the latter is how people like Adam Minter see it. In fact on an episode of On Point with Warren Olney, Adam Minter argues:

“….you’ve got a far more, far more complicated story than what is being presented in just the new york times and especially the This American Life Story”

In contrast, Mike Daisey appears on that same show and says “Lets stick a knife in this whole complicated thing for starters, because this isn’t actually that complicated”. That is the biggest fiction Mike Daisey was selling.

Paul Krugman agrees that when Jamie Dimon says he just wants to be loved respected, that we should take him at his word

This seems completely right to me. When you make a billion dollars a year, you can buy anything you want — which means that goods and services yield almost no marginal utility. What you crave, then, is what money can’t buy: respect.

Actually, I’ve seen this in action at meetings where financial big wheels and professors mingle. You’d think that the people with the big bucks would be confident; on the contrary, they’re insecure, because they want respect for their minds

The thing is hugs are cheap. Bad policy is expensive. Somebody give those boys some hugs. I don’t know why there is not a Hedge Fund Manager and Financial Executive Hugging Task Force.

Scott Sumner writes

Now as we all know, [Krugman’s] model is wrong. It predicts that core inflation will plummet steadily lower when in a liquidity trap. If the Fed is targeting inflation, then there is no liquidity trap, no paradox of thrift, no paradox of toil, no fiscal multiplier, no “Depression economics.” And as we saw in 2010, when the Fed observes core inflation fall below their 2% target they do policies like QE, and extended promises of low interest rates, in order to raise core inflation back up near 2%

I am not sure exactly which model Scott is referring to, but in Paul’s standard story concerning Japan the liquidity trap comes about because the Central Bank is targeting inflation or at least people believe it to be.

Indeed, in that model if the central bank were willing and able to target Nominal GDP then the liquidity trap would disappear.

For

c = y = D-1 y* (P*/P) (1+i)-1

where c is consumption, y is real income P is the price level, D is the discount factor, i is the nominal interest rate and * indicates long run values as opposed to current values.

NGDP targeting implies P*/P = y/y*

So

c = y = D-1 y* (y/y*) (1+i)-1 = D-1(1+i)-1y =>

D = (1+i)-1 =>

If D < 1 then i > 0

and so there is a non-negative nominal interest rate that clears the goods market.

In the current context the interpretation would go like this. The Fed would assure the public that NGDP would grow at 5%. Thus, if for any reason real GDP collapsed by 6% in 2008 – 2009, the Fed would produce 11% inflation so as to ensure that Nominal GDP did not fall.

However, knowing that 11% inflation was coming real GDP would likely not fall as much. If I am reading Scott right then he suggests that the real GDP would not fall at all.

My take would be that both real GDP and inflation would likely fall in the face of something like the banking failure. However, the promise by the Fed to bring nominal spending back to path as soon as possible would cause a more rapid turnaround than we saw because there would have been an even more aggressive expansion of business investment and faster recovery in the stock market.

Greg Ip and Felix Salmon have sparked renewed interest in the output gap debate.

Greg Ip writes

Or you could go with a simpler but more pessimistic explanation: both the level and growth rate of American potential output is much lower than we think. This would resolve all these puzzles: GDP growth of 2.5% is above, not at, trend, the output gap is closing, and it was probably smaller than we thought to begin with. That would explain why unemployment is falling so quickly, and why core inflation hasn’t fallen further. The excess supply of workers and products that ought to be holding back prices and wages is not as ample as we thought.

You can attack this problem various ways with Aggregate and Quasi-Aggregate analysis and I see a lot of economists and bloggers doing that.

I’d, however, encourage everyone, as well, to think of the disaggregated story that we are telling here. If trend GDP is overstated, then we are arguing that one or more sectors of the US economy will is less capable of producing output over the next decade or so, than we would have otherwise thought.

So then we might want to ask – what are those sectors?

Since, I don’t know exactly what folks will say I will offer this:

The majority of the output gap – over 5 percentage points of GDP – could be closed by a return to trend of the construction of housing, hospitals and medical facilities and public infrastructure as well as an increase to trend in the production of transportation equipment.

So one, direct hypothesis would be that these things cannot or will not return to trend.

I have spent a fair bit of time trying to argue that the total stock of housing is below trend and that housing would become extremely tight leading to rapidly rising rents. So far rents do appear to be rising and as of now – rising rents consitute the bulk of the inflationary gains.

If we are to ask why there is inflation in the face of slack, the simple answer is there is not. There are not enough houses in America and the price of housing is indeed rising.

If we are to ask why the market doesn’t correct, then the most obvious answer is collateral constraints. They may not be the right one, but it’s a story that seems consistent all up and down the line. Its even consistent with the observation that an ever increasing number of homes are bought with cash by investors who intend to rent them out and that some new multi-family housing projects are coming on line with 100% equity.

However, this is not something permanent. The price of houses – or more specifically land – will not continue to fall forever and indeed appears close to bottoming.

A similar phenomenon explains the slowdown in the purchase of transportation equipment which has been heavy and hard among low FICO buyers in states with rapidly falling housing prices, but has returned almost to trend among high FICO buyers in states with slowly falling housing prices.

Public infrastructure faces similar constraints. The decline from trend in hospitals and medical facilities is more of a mystery.

So, if we think these things will repair themselves then we have an obvious path back to trend.

I don’t want to get too invested in this but a cursory look at the data suggests that GDP is likely to grow above trend in the coming years because two very high productivity export sectors are expanding – computers and gasoline and distillates.

Call this the Apple and Exxon effect, but even without increased consumption by Americans, things which potentially return a lot of GDP per worker to America are growing.

Which brings me to make a quick note on one Felix Salmon’s points

In other words, in order to keep up a steady rate of GDP growth, we had to saddle ourselves with ever more cheap and dangerous debt.

Then, suddenly, the growth of the credit markets screeched to a halt, and we had a major recession. And since then, the size of the credit market has been roughly flat.

It makes sense that if we needed ever-increasing amounts of debt to keep up that long-term GDP growth rate, then when the growth of the debt market stops, our potential growth rate might fall significantly

This sounds compelling to a lot of folks but to me its not clear what the underlying story is.

In terms of household debt as a percentage of PI there were a series of run-ups but as you can see they are mostly about mortgages.

The run-up in the 80s was the Volker dis-inflation. Remember that when both interest rates and wages decline from dis-inflation, principle balances as a percentage of income rise mechanically for long term debt.

The second run-up was of course the housing bubble. A small portion of this went into the increased production of single-family houses, though at the expense of mutli-family and manufactured housing. However, most of it went into the price of land. Which meant that some of it was simply a wealth transfer between Americans.

Now, there are some people – some I know – who will never work again because they sold their house at the top and moved into a rental. That possibly reduces long-term GDP if the number of workers has fallen. However, this group of people is likely small and balanced out by those who will not get to retire when they hoped because they took on larger mortgages.

Some of the increase in debt funded a steady increase in net real imports over that period. However, this does not add to GDP and as it retracts we should not expect GDP to decline.

The New York Times has updated it’s Mike Daisey op-ed with the following:

Editor’s Note: Questions have been raised about the truth of a paragraph in the original version of this article that purported to talk about conditions at Apple’s factory in China. That paragraph has been removed from this version of the article.

Here is the paragraph that they excised, which I was able to find here:

I have traveled to southern China and interviewed workers employed in the production of electronics. I spoke with a man whose right hand was permanently curled into a claw from being smashed in a metal press at Foxconn, where he worked assembling Apple laptops and iPads. I showed him my iPad, and he gasped because he’d never seen one turned on. He stroked the screen and marveled at the icons sliding back and forth, the Apple attention to detail in every pixel. He told my translator, “It’s a kind of magic.

As the press release (pdf) from This American Life confirms this is one of the stories that Daisey’s translator denies ever occurred. So I think Daisey perhaps needs to expand his apology which says his only regret is allowing This American Life to excerpt from his monologue, which was theater and not journalism:

What I do is not journalism. The tools of the theater are not the same as the tools of journalism. For this reason, I regret that I allowed THIS AMERICAN LIFE to air an excerpt from my monologue. THIS AMERICAN LIFE is essentially a journalistic - not a theatrical - enterprise, and as such it operates under a different set of rules and expectations. But this is my only regret.

Writing an op-ed for the New York Times is also not theater, so I’m thinking we will not remain his “only regret” for long.

I’m hearing a lot of people say the real tragedy is that the things Daisey pretended he saw actually do happen and this whole debacle does a disservice to that truth. I side more with the wise Adam Minter, who is quoted here by Rob Schmitz, the journalist that caught Daisey in the first place:

“People like a very simple narrative,” said Adam Minter, a columnist for Bloomberg who’s spent years visiting more than 150 Chinese factories. He’s writing a book about the scrap recycling industry.

He says the reality of factory conditions in China is complicated—working at Foxconn can be grueling, but most workers will tell you they’re happy to have the job. He says Daisey’s become a media darling because he’s used an emotional performance to focus on a much simpler message:

“Foxconn bad. iPhone bad. Sign a petition. Now you’re good,” Minter says. “That’s a great simple message and it’s going to resonate with a public radio listener. It’s going to resonate with the New York Times reader. And I think that’s one of the reasons he’s had so much traction.”

And Minter says the fact that Daisey has not told the truth to people about what he saw in China won’t have much of an impact on how the public sees this issue.

Minter’s criticism of the overly simplistic story that misses the complicated reality of China’s factory conditions was true before Daisey’s lies were exposed, and they are true still.

Some commenters are pushing back on my previous post by suggesting that the GM bailout was desirable and the AIG bailout wasn’t. I don’t have hard evidence for this, but I’m pretty sure economists in general are more supportive of the bailout of AIG than the bailout of GM. For one thing AIG is a financial company whose failure would have brought down many banks, and we have known for over 100 years that preventing banking panics is an important function of central banks. Justifying bailouts of manufacturers on the basis of economies of agglomeration does not fit within the well understood and commonly agreed upon tenants of central banking. Regardless of the end desirability of the GM bailout, it is certainly a more controversial thing for a central bank to do.

More importantly though, the issue here is that Treasury issued a notice that exempted companies which the government became an owner of in a bankruptcy preceding from the established section 382 of the tax code. Are those who criticize the AIG tax benefit but not GM really arguing that this ruling should be amended so that whether section 382 applies is subject to the discretion of the Treasury? For one thing I’m not sure that would be legal (somebody who knows more can tell me if this is the case). But even if it were it strikes me as pretty undesirable to give administrations that level of discretionary taxing power, essentially allowing the President to provide a potentially massive tax benefits to companies it bails out if it feels like it. No, I would rather not give Presidents more arbitrary bailout power, especially of the kind that tends to be hidden and unreported.

Via James Pethokoukis, comes a statement from Elizabeth Warren and three other former members of the TARP Congressional Oversight Panel with some harsh words for the special treatment given to GM:

“When the government bailed out GM, it should not have allowed the failed auto giant to duck taxes for years to come. That kind of bonus wasn’t necessary to protect the economy. It also gives GM a leg up against its competitors at a time when everyone should have to play by the same rules – especially when it comes to paying taxes”

Actually Warren didn’t quite say this. Despite the fact that AIG, GM, and Citigroup all benefitted from a special Treasury rule that allowed them to, as Warren puts it, “duck taxes”, Warren only called attention to the money given to AIG. Here is the phrasing actually used:

“When the government bailed out AIG, it should not have allowed the failed insurance giant to duck taxes for years to come. That kind of bonus wasn’t necessary to protect the economy. It also gives AIG a leg up against its competitors at a time when everyone should have to play by the same rules – especially when it comes to paying taxes.’’

The basic issue is this. When a company has a net operating loss (NOL) in one year, they can carry these losses forward into later profitable years to lower their tax bill. Normally, when a company goes bankrupt and ownership stake is changed by more than 50%, the NOLs disappear. According to a paper by Mark Ramseyer and Eric B. Rasmusen, GM had $45 billion in losses, with a book value of $18 billion, that the Treasury’s special exemption allowed them to keep. According to Warren the exemption has provided AIG with $17.7 an extra billion in profits. It’s unclear why you would complain about AIG receiving this tax bailout and not complain about GM doing the same.

Am I missing something here? It’s quite possible. I’m not a tax lawyer or an accountant. But from where I’m sitting, James Pethokoukis is correct that it is strange to complain about AIG and not GM. The only reason I can see why Warren would do this is that she is a politician running for Senate and she doesn’t want to alienate liberal voters and unions who support the GM bailout, including the part that lets them “duck taxes”.

It’s worth noting that, hypocrisy aside, Warren is right these secret bailouts are a bad idea. People tend to ignore these costs when considering bailouts, indeed many pundits seem completely unaware of them, which bailouts them seem cheaper then they really are. I don’t think we’ll ever be free of the problem of bailouts, and letting politicians hide billions of dollars in costs makes it more likely that the bailouts we get will be even bigger.

Matt Yglesias responds to a reviewer who wonders how poor folks housing will differ from rich folks housing in the post-regulatory utopia.

If you imagine a city with fewer regulatory constraints on building, then in dense neighborhoods you would have a blend of newish buildings with the most modern amenities and older buildings that are structurally sound but a bit unfashionable, a bit more likely to be suffering from plumbing problems, and lacking in some of the latest features. What’s more, since society gets wealthier over time the older buildings will probably have smaller units on average. Within tall buildings you’d also expect to see meaningful price differentials based on vertical location. I am a density advocate, but there are obviously some downsides in terms of noise and light that are mitigated on higher floors.

The most likely differentiation is size. If you look at the housing habits of current rich people in areas not constrained by land prices you get things like this

So think about it like this. Suppose NYC living costs go into complete regulatory free fall. Prices on housing and office space collapse, bringing down labor costs, and so on. We might expect prices to hit levels where land is not constraining. Indeed, because productivity is presumably higher in a dense area we might expect them to fall below that level but lets hold off on that.

The builders here in North Carolina say that it costs them about $200 a square foot to put up high-rise construction.

Average home price in Manhattan is $1.4 Million, which implies that the current – mostly wealthy – residents of Manhattan would move into apartments that were on average 7000 sq ft. That is slightly bigger than what you expect to see in upscale new Southern neighborhoods where the stereotypical number is 5000 sq ft.

It also means that some folks will own $20 million apartments which would buy you 100,000 sq ft – about in line with the Gilded Age Newport, RI mansions.

Though, if you are in the market for a 100,000 sq ft apartment one imagines that you intend to actually gild it with gold toilets and such. Those amenities would bring the turnkey cost significantly north of the pure price of living space.

And, by idiots we mean not that people are of low intelligence necessarily but people who fail to leverage the knowledge and intelligence of others.

Via Robin Hanson

Next, we look at the final round where information about disagreement is made public and, under common knowledge of rationality, should be sufficient to eliminate disagreement. Here we find that individuals weigh their own information more than twice that of the five others in their group. When we look separately at those who err by disagreeing in round 1, we find that these people weigh their own information more than 10 times that of others, putting virtually no stock in public information. This indicates a different type of error, that is, a failure of some individuals to learn from each other.

This is potentially – maybe some people have worked this out carefully – a serious source of co-ordination problems.

Everyone knows the classic rhetorical: If all your friends jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge would you?

The problem here is that there is general agreement that the answer is no, but in a world of rational people the answer is yes. If a bunch of people show a high degree of confidence that jumping off the bridge is the right thing to do that is a sign that they know something you don’t.

So, why is the answer no?

This experiment would suggest that the probability that all your friends are idiots who have happened to stumble on a bad idea is higher than the probability that jumping off the bridge is in fact a good idea.

In an ideal world agreement wraps around the world, so that you get information from your friends who have gotten from their friends who have gotten it from their friends and so on until the entire population is connected into a giant hivemind, through which information is rapidly transmitted.

Idiots degrade the signal and mean that information does not flow very far and wide disagreements are possible, especially between people who do not share broadly similar social networks.

In the coming months we would like to see as many FOMC members are possible use the phrasing

are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the Federal Funds rate through at least late 2014

what comes before that is not very important and indeed more helpful if it reflects the member’s idiosyncratic outlook on the economy. What is important is that given developments in the economy the members remain convinced that low levels are likely to be warranted.

A twitter follower notes

Karl Smith (

@ModeledBehavior) has a quixotic focus on Apple’s cash reserves. http://modeledbehavior.com/2012/03/14/iphones-and-oil/It’s tre bizarre.

Apple does loom large in my thinking for a number of reasons.

One, Apple revenue looks to grow by something $70 Billion this year. Expectations for nominal GDP growth are around $500 Billion. So, how one calculates Apple’s value-added to the US economy has a non-trivial impact on calculations of economic growth.