You are currently browsing the monthly archive for July 2011.

Publically I have remained steadfast in my insistence that a deal would get done, or worst coming to worst the President would invoke the 14th Amendment to avert a crisis. There will be no default I said.

I will admit now though that at the dinner table I confessed to my extended family that I saw a perhaps one percent or more chance that a default would occur. And, of course a one percent chance on such matters is something to lose serious sleep over.

Brad Delong asks

Macro Advisors projects 3.1% real GDP growth over the next four quarters, then rising to 4.0% real GDP growth for the second half of 2012.

It could happen. But where is the demand supposed to come from?

I haven’t seen the internals of the Macro Advisors model but these numbers don’t sound off to me as a baseline. How would they come about.

1) Rapid increase in multi-family housing built to rent. If rents continue to rise then profits on new multifamily structure will be high. Tight credit for young borrowers combined with high gas prices will also push large rental complex demand.

Here I actually have some fear as to whether the North East corridor will be friendly enough to new development to allow this to proceed at its maximum pace. However, the sun-belt is still very open to bulldoze-and-build. Not to mention it is currently heavily car dependent, so I could see some rapid changes beginning to take place.

2) An end to fiscal contraction. The contraction in State and Local spending has been an intense blow to both employment and GDP. However, this should be coming to an end. I do not expect a government hiring boom anytime soon. However, we don’t need a boom. What we need is for State and Local to simply stop contracting.

3) Net Exports. This is a hard call with all that is going on in Europe but both inflation and growth in the developing world should be slowing US import growth and increasing US export growth.

4) Believe it or not, consumer spending. Consumer spending has not been a superstar but until the last quarter it was decent enough. Gas prices are the biggest variable here, but again I do not see the fundamentals supporting oil over $100 a barrel right now. I haven’t had a chance to read the latest thinking on the energy markets, but to me there looks to be too much supply in the wings to get oil this high.

Unlike 2008 there is much less incentive to “ground speculate.” That is slow pumping in the hopes that future prices will be ever higher. This is because we see a lot of potential energy supply coming online and we see a US market that seems to be moving rapidly towards conservation and is unexpectedly sensitive to price.

5) Continued heavy investment in Equipment and Software by businesses. The current strength in E&P is hard to explain and its easy to see it going away. However, if you just assume that something that we don’t fully understand is boosting investment and look at it from a business cycle perspective then a strengthening economy should lead to even more rapid E&P accumulation.

Now, of course predictions are hard – especially about the future. The wave of forecast downgrades may continue. However, gloom is not a model. You have to base your best guess on your best understanding of the underlying economy. To me that points to growth, even if we have seen a string of disappointments over the last nine months.

Not much time. Haven’t even read the full report yet

A few questions though based on a quick skim:

- Have we ever had this much investment in an economy so weak?

- How would you put this into a traditional Austrian Box? Are we in a mal-investment phase now. It would seem must be the case that the roundaboutness of production is increasing dramatically as Equipment & Software is rapidly outpacing Consumer Sales?

- From a PSST/Kling framework does this make sense as the Great Depression Part II accept this time the Telecom is playing the role of the Tractor?

This still seems consistent with a New Keynesian credit constrained household model with a contracting government. Construction still remains the really odd sector though it seems to flattening out and the signs for a construction boom are still building

I still lean towards increasing growth in the second half and going into 2012.

What are the issues: obviously sovereign debt here and abroad and oil. Oil and gasoline look to be trading to high to me but I am of course very interested to see what Jim Hamilton has to say about it.

A regular reader asks

Wait… did Mr. Karl “one of the largest downsides of being born is that you have to die” Smith have a child?

If so then, seriously, congratulations. I hope you will see that “happiness”, “gratification” and “joy” are truly different emotions, related but not substitutes for each other.

Coming to parenting honestly means acknowledging that while a joy to me, birth is an unrequested imposition on my son. He like everyone else – did not ask to be born.

It is in part because of that, that I owe him the happiest existence I can manage.

Texas manufacturing survey comes in a bit lower than I would have hoped but moving in the right direction. From the Dallas Fed

Texas factory activity expanded in July, according to business executives responding to the Texas Manufacturing Outlook Survey. The production index, a key measure of state manufacturing conditions, rose from 5.6 to 10.8, suggesting output growth picked up this month.

Other measures of current manufacturing conditions also indicated growing activity, and the pace of new orders increased. The shipments index rose to a reading of 7.8 after coming in at zero last month. The capacity utilizationindex was positive but remained near zero, indicating little change over the prior month. The new orders index rose sharply from 6.4 in June to 16 in July. Thirty-four percent of firms said order volumes increased this month, the highest share since November 2010.

Expectations regarding future business conditions were generally more optimistic in July. The indexes of future general business activity and future company outlook edged up this month after trending down in the first half of the year. Several indexes of future manufacturing activity, including production, rose in July while others edged down but remained in solid positive territory.

My thesis remains that we saw temporary disruptions in an otherwise upward trend. I also remain confident that the debt shenanigans will but overcome before they wreak any real damage. Consequently I looking for a fair pick-up in growth by the end of the year.

Paul Krugman reads his Modeled Behavior

Conservative economists love to point out that means-tested programs like food stamps in effect create high marginal tax rates for low-income families, since they lose benefits if they work and earn more. Well, means-testing Medicare would do the same thing: your reward for a life of hard work and accumulation will be higher copays and deductibles.

Actually this is a pretty basic Public Finance result. However, it is one that is probably going to take a lot repeating to make it into the conventional wisdom. So, here I go again: means-testing is a marginal tax increase.

And, to be clear, its not just a “tax increase” it’s a marginal tax increase. The kind folks who focus on tax incentives should fear most.

Cutting Social Security benefits is a marginal tax increase as well. I’ll do more on that when I get the chance but its worth getting the meme started.

Last week speaking on the state of the national economy I was asked by conference attendees how they should prepare for a default by the United States. “Cross your figures” was my reply.

Yet, then I assured them that there would be no default. All posturing aside, at the end of the day the Republic would not be brought down by such things.

Ezra Klein has a nice post on the dynamics inside the room vs the dynamics outside the room.

It always feels different in the room. In the room, everyone wants a deal. They want their name on legislation, in history books. They want to do the big things and make the hard choices. Then they leave the room and they learn their supporters don’t want the choices made if they’re going to be hard. They learn their colleagues know their names won’t be in the history books, and so they’re more concerned with making sure their names are on their desks in the next congress.

This is certainly true. What I would tack on, however, are the outside-outside dynamics. The men and women who will ultimately vote on the debt ceiling are men and women. They are humans with human frailty and one of those is self-doubt.

Everyone has a different set of elites that they feel uneasy facing. For some it is Nobel prize winning economists. For some it is billionaire entrepreneurs. For some it is Wall Street titans. For some it is the grand-old men and women of the civil service and the military.

Yet, I am betting that just about every one of the 435 members of the House has someone from whom a stern dressing down would leave a lump in his or her throat.

And, so when all of the elites line up to say that default is not an option, that’s an emotionally intimidating force that these men and women – most of whom are fairly ordinary outside of their positions as members of congress – must face.

When one of those elites is Grover Norquist, Grand Poobah of the small government movement, I find it hard to believe that the members will not yield.

Asked if Obama’s warnings that default would be a "disaster" were true, Norquist said that as far as he knows, they are. Via TPM

"Look I assume it’s a disaster, there’s no reason to assume otherwise. It’s gambling with the economics of the country to get that far," Norquist said. "We need to get to where first of all we can cut some spending, not raise taxes. As much as you can get is as much as we should fight for. But again: rather than close the government down or go into default, let’s take it to the American people, go into the next election and fix things then."

David Altig has some awesome charts comparing this recovery to the last two recessions. Let me talk through two of them.

Here is the first. It shows a couple of things. One GDP growth has been slightly less robust in the 2009 – present period. But lets just look at the composition.

The largest blue bar in each area is PCE – that’s consumer spending. Notice how much smaller it is than the other two recoveries. That’s not a big a shock. We knew that the consumer was hurting. I’ve posted tons of charts showing the “check mark” in retail sales.

However, really take a look at the green bar. That’s investment in the sense that most people think about it: Equipment and Software. A lot of investment is actually buildings, but that’s not what the average commentator is talking about when he or she mentions investment.

They mean computers, software, diesel locomotives, die presses, etc. The type of stuff that makes other stuff. Not the type of stuff that houses other stuff.

You can also see – since it is so pertinent to the current political debate – that government was a huge part of the post dot-com recovery, and a tiny part of the 1991 recovery, but has played no part of this recovery.

That, however, is peanuts in my mind relative to the deeply interesting boom in Equipment and Software. It’s a little surreal and its hard to know exactly what to make of it.

Not only that but combine it with this breakdown of PCE

Look at the strong growth in consumer durables in the current recession. Much stronger than any time before. Also, look at the massive weakness is service spending.

Now part of this has to do with how hard and fast durables declined during the collapse. Nonetheless it is fascinating to see that all of the spending that is going on in the economy now is on what could loosely be termed capital.

Its either equipment and software, which is capital for businesses. Or consumer durables, which is like capital for households.

Goldman Sachs isn’t quite sure

While the decennial census data are from the largest sample, we do not believe it is appropriate to ignore the other sources. …

With the 2010 Census results in hand, we would now say that excess vacancies in the housing market are 1.5 to 3.5 million units—a wide range, reflecting discrepancies in the available data.Clearly though, the census results suggest the risks to our previous estimate of 3.5 million units are to the downside

If there are 2 million shadow households and 1.5 million excess housing units then we are as of right now, 500K units in the hole – should the market immediately clear today.

Even at the high end estimate of 3.5 million we are looking at an excess of only 1.5 million units and only roughly 200K new unit scheduled to come on line in the next 12 months. If housing starts remained depressed throughout 2012 then natural household formation will push us into shortage.

I do, however, think the high end estimate is too high and that when shadow households are factored in we are already looking at a shortage.

Expect higher rents over the near term and as a result higher core inflation. Those price increases, however, will reignite a building boom and support lots of new construction. We don’t want to over-react when it comes.

Yglesias brushes aside a Heritage foundation chart showing that the Affordable Care Act was bad for jobs.

Clearly, though, no fair-minded person actually interested in the subject is going to be persuaded by this kind of nonsense. I think it’s really too bad that conservative institutions spend a fair amount of time and energy on projects whose only possible effect can be to mislead their own constituency.

Here is the chart he references.

You can see the trend in month-to-month growth both before and after the passage.

I am elated to see Matt write a post like this because it PROVES and I mean proves, that despite my wife’s frequent protestations to the contrary, I am not the most intellectually detached blogger in the blogosphere.

For I – unlike Matt – see why this chart could be confusing to some fair minded people. And, I – unlike Matt – see the need to explain exactly why this chart is misleading.

Here goes:

Suppose that the pre-ACA trend had continued unabated. Then on top of the surprisingly strong job growth of April 2010 we would have kept accelerating at a rate of 67K jobs per month. At that rate we would currently be adding jobs at roughly 1.2M per month every month.

As you can see below, even when the economy is cooking it rarely cross 400K jobs per month.

The absolute historical record is 1.1M in 1983 and that was the result of the resolution of strike against AT&T.

If you look at the chart then anyway you slice it the private sector job growth rate in April of 2010 was near its likely peak and so a slowdown in the rate of improvement was inevitable.

You could make the argument that one should have expected private sector growth to drift upwards into the high 300. However, that’s a much more subtle shift that’s going to be harder to attribute to the ACA.

The fundamentals still lean towards growth – that’s my story and I am sticking to it. Nonetheless, the real time data leaves me squirming in my seat.

Initials Claims

New claims for unemployment insurance bumped up again this week. We are now back around 418K level. What disconcerting here is simply that we bumped up – the series is volatile – its that we are not seeing the kind significant downward pressure I would expect. I would have wanted to break into the 350s by early Fall. That seems highly unlikely at this point

Philly Fed

Our second regional manufacturing survey is out and its not as good as we could have hoped. We moved from mild contraction last month to just a bare expansion this month. That’s a move in a positive direction but it was to be expected.

The narrative I was working from was that manufacturing disruptions were temporary. Given that we should be seeing upward movement. I would have wanted to see something stronger.

Sane conservative economists recognize that not raising the debt ceiling on August 2nd would be a disaster. Sane conservatives understand that the ratings agencies will lower our credit rating if we won’t raise the ceiling, and that we have almost $500 billion in maturing treasuries that we need to roll over in August alone which, as UBS argues, is a problem:

“The mistaken view that interest payments to US Treasury-holders could easily be prioritized, avoiding default indefinitely. This view requires that investors willingly roll over their holdings of Treasury debt and does not take into account the sharp increase in interest rates that may result.”

As Lawrence White explains, and S&P agrees, prioritizing payments is a default:

“…if the federal government delays payment to anyone, then certainly in a common-sense sense, the government has defaulted on its obligations….I believe that the financial markets would not be copacetic [if bondholders were repaid but other creditors weren’t]….They would realize that the government was stiffing one set of claimants who are creditors, and the markets would worry that they might be next.”

Our lenders understand better than those arguing that we can simply cut government spending 30-40% overnight, and lenders understand that voters won’t tolerate having foreign banks get paid while they suffer. Neil Buchanan agrees:

“Foreign holders of Treasuries will understand that it is politically untenable to pay foreigners but not Americans…Can you imagine the firestorm if Americans were told that we cannot afford to pay Social Security recipients, because we have to pay foreign banks and governments first? …No matter how strong the argument that doing so is necessary to protect our credit rating, the bottom line is that the government would be favoring foreigners over Americans. Any foreign investor would know that this is not politically sustainable. They would have every reason to dump our bonds, or at least to require much higher rates of return.”

If interest rates go up, that $500 billion we need to roll over is going to be a lot more expensive. As Barry Eichengreen says, “[e]vidence that the inmates were running the asylum would almost certainly precipitate the wholesale liquidation of US Treasury bonds by foreign investors.”

If I haven’t convinced you that not lifting the ceiling would be hugely problematic, then perhaps these sane conservative economists (and Richard Posner) will:

Gary Becker: “That Congress will have to raise the debt limit this summer is a no-brainer since revenues are not anywhere near large enough to cover government spending. Without a boost in the ceiling, the federal government will be unable to pay its bills, including pay to federal employees.”

Keith Hennessey: “Congress must raise the debt limit. Not doing so would eventually lead to defaulting on Treasury bonds, a potentially catastrophic event.”

Douglas Holtz-Eakin – “Yes, Congress should raise the debt limit. Being a good steward of the U.S. credit rating means that it has to pay Obama’s credit-card bill. And it should do so as quickly as possible — on the day it returns from recess.”

And a video from Holtz-Eakin

Glenn Hubbard: “The debt ceiling must be raised – not doing so is irresponsible”

Richard Posner: “No doubt before the political and economic damage becomes too severe, the Republican radicals in the House of Representatives will relent and the ceiling on borrowing will be raised. Before that happens interest rates may rise, and stay higher, because of doubts about the basic competence of American government. Those doubts, plus the higher interest rates they engender, may deepen the current economic downturn, which in turn will reduce tax collections, increase transfer payments, and in both respects increase the federal deficit… Why Republicans prefer flirting with failing to raise the debt ceiling by the August 2 deadline to accepting the deal tentatively worked out between President Obama and Speaker Bohner…is a deep mystery.”

I’m trying not to get shrill here, it’s getting hard.

A quick reminder, because this will take some persistence, that means testing is a marginal tax increase. Adjusting to a new chained CPI measure will also in many cases be marginal a tax increase – both through the tax code and the spending code.

However, in this iteration of my infinite part series I am going to pivot off of something Yglesias said that echoes a long standing position of mine:

There is no present-day economic problem that can be laid at the feet of high current levels of federal spending. So let’s not sweat the 2020s. Maybe we’ll invent some super-useful but expensive technology that merits giant spending. Who knows? Most likely, voters will continue to demand certain kinds of public services and that will cost money. One such service is health care. Systematic reform of the exceptionally high cost structure of American health care would, fairly reliably, lead to a lower level of future spending. Just saying “cross my heart / hope to die / stick a needle in my eye / public sector health care spending will be lower” doesn’t achieve much of anything.

Future problem necessarily exist in the future. And, because of adding up constraints, solutions to future problems often exist only in the future as well.

For example, the solution to not spending a lot of money on Medicare in 2035 is more or less to not spend a lot of money on Medicaid in 2035. Unfortunately for those worried about the problem, it is currently 2011. So there isn’t a lot you can really do about it.

More completely, part of the reason you can’t do anything about this is that Medicare spending doesn’t simply come out of the ether. Its not like we could be spending $100 Billion but we are just flippantly choosing to spend $600 Billion. There are social demands, political constraints, technological opportunities and obstacles and ultimately an equilibrium that emerges from the political process.

In 2035 there will be similar forces and they too will produce some equilibrium. Trying to understand that equilibrium is hard enough, trying to control it strikes me as a bit silly.

My best guess at this point is that the equilibrium in 2035 will be like that in 2011 only more so. That is to say, the desire to spend on entitlements will trump the desire to hold down marginal tax rates and concerns about the deficit will to bring the two in line. The result will be higher taxes.

I say this not to argue in favor of it but simply to say that this looks like the inevitable outcome. Right now I don’t see how a radically different equilibrium emerges.

Brad Delong posts the sentiment that usually requires at least a few glasses of Pinot before speaking its name

Wall Street especially stands to gain the most from a rapid recovery and a high-pressure economy–even one that comes along with slightly higher rates of inflation.

The problem is not that the modern state is an executive committee[1] for managing the affairs of the rentier class: there is no rentier class and there has not been one for a century. The problem is not that the modern state is an executive committee for managing the affairs of the bourgeoisie: every day I pray to the Holy Name of the One Who Is that it become such…

On one level I don’t think it’s a well kept secret that technocrats often prefer the greed of the plutocrats to the passions of the populists. Though, I rarely hear it in such a plain and sober context.

Nonetheless, I must admit that in more than one rum-soaked rant I’ve bellowed – echoing another Delong post – that at least the rich have the good sense to steal the silver before burning down the house.

Or at leas they did. These days one cannot be sure. And, what good are the moneyed elite if they are either unwilling or unable to whip the GOP into line.

Via Calculated Risk, Tom Lawler on the housing stock

Total housing production in 2011 should fall south of 600,000 units, compared to the 2.092 million housing units that came on line in 2006.

Sadly, there are no good, timely data on the likely number of housing units that will be lost to various factors (demolition, conversions, disaster, etc.). The Census 2010 data suggested that the annual “scrappage” rate was substantially lower than other Census data had suggested last decade, though that could well have been related to the housing boom years, with higher conversions or units added from non-residential use than various surveys (based on relatively small samples) suggested. Anecdotal evidence suggests that scrappage rates of late would not be that low, and a conservative estimate for 2011 would be in the 250,000 range – implying growth in the housing stock for the calendar year of under 350,000 units.

Note that up until recently – note completely sure on his current stance – Lawler has been more pessimistic about housing than I have been. He leans heavily on vacancy rates, while I’ve tended to look more a demographics.

Yet, now all the stats are beginning to align. In a way this is like 2005 all over again. In late 2004 there were a number of people from the outside who started to grumble about the unsustainability of housing prices. There also were those who told stories about how this time was different.

And, let me be honest. Many of those stories were compelling. I continued maintained that the price bubble would eventually pop but I count that as more an act of luck than insight. I don’t want to relitigate that battle but I will say the soft landing people did not have a ridiculous case.

Now the same thing is happening in housing supply. There were those of us last year looking around and saying – this is just not sustainable. Yet, people told stories about vacancy rates and getting the rot out that were compelling. Lots of people said we are not going to see booming construction for a long time and seemed to feel the fundamentals backed that up.

Yet, over the beginning of 2011 lots of data series have started to turn in the same direction. We are seeing growing consensus that this is simply not sustainable and something is going to have to give.

Moreover, just like a price bubble, this housing shortage is a growing phenomenon. The longer it goes unaddressed the bigger the correct will be. And, quite frankly there is no reason to think actual housing supply will begin to tick up in the next 12 months. The lead time on home building is just too long.

So we are probably looking at 2 years minimum before we get a significant reduction in pressure. All the while shadow households are still forming. Couples are still getting married or waiting to get married. Babies are still being born, etc.

When housing corrects, I have to guess that it will correct hard.

For reasons both Macro and Micro we should suspect that this period of unusually low GDP growth will be followed by a period of unusually high GDP growth.

From a disaggregated, but not quite micro, perspective my continuing thesis includes:

- Home construction is unsustainably low

- Household formation is unsustainably low

- Even given (2), (1) is so bad that vacancies are falling and rents are tightening

- Yet, (2) is implicitly caused by (1) because weak construction is depressing employment

Thus there are the makings of a boom stirring. Construction will pick up. This will lead to falling unemployment. This will lead to rising household formation. This will lead to ever more construction.

In a world of high gasoline prices, low crime and weak household balance sheets there is every reason to expect that we will see a historic increase in new urban apartment complexes.

This will be exacerbated by the public school flip that it will set off. Young couples will flood into low crime, cheap transportation and quite frankly the only available housing of the city. They will send their smart well prepared young children to public schools. They will show up at the local PTA. They will lobby the city government for reform.

This will cause a dramatic rise in the performance of city schools, making urban neighborhoods even more attractive. Gentrification will accelerate. The suburbs will reach a tipping point where the schools are worse and the neighborhoods less prestigious. The reversal will intensify as high status becomes associated with raising a family in the city.

In a relatively short time, American cities will have flipped inside out. Or right side out given your perspective. America has always been the outlier here. A flood new skyscrapers will be created.

While the North East corridor is primed for this type of thing given its current built environment, new building permitting may play a vital role. We may be looking at the new urban south. I am thinking Florida, Texas, Georgia and North Carolina. These are places where its still legally possible to raze whole neighborhoods to put up big shinny buildings.

They also have not insignificant urban cores in Tampa, Miami, Houston, Dallas, Atlanta and Charlotte. Austin and Raleigh are much smaller but are hooked up to the fast growing tech industry.

This trend will be enhanced if driverless taxis are approved in the near term as this will take the pressure off of new mass transit construction.

This is of course, over the medium term. Over the longer term we get virtual schools and offices, tiny passengerless car-robots and cheap solar power which may promote a resuburbanization.

I’m putting together an “economic update” presentation for next week and am including a figure I and just about everyone else I have seen do these things includes. However, it reminded me of how little I see it out on the blogosphere.

It’s total employment in the United States over the last 20 years:

Currently we have fewer people working in America than just before the dot-com bust. Taken all together this has just been a brutal decade on the jobs front.

The 90s were of course unusually good but even in historical perspective the current period is striking. Levels over the last 70 years.

And on a log scale

Yglesias gets it right on the question of whether workers are overpaid.

The more I think about this question, the less sense I think it makes. In a competitive labor market, nobody is “overpaid.” If one restaurant pays its line cooks more than another restaurant, it’s presumably trying to get privileged access to higher quality workers. The question is whether or not public agencies are purchasing unduly high-quality labor. And that’s not a question that it makes sense to ask in general. Baltimore probably should be investing more in obtaining the best police officers possible than Bangor. Doing statistical controls ends up sort of further obscuring this.

There are certain issues people seem to have a lot of trouble with – even economists. This is one of them. As Matt alludes to, are you say labor markets work or not. If you are saying labor markets basically don’t work then that’s a major statement and we should really talk about it more in depth.

Otherwise, what you are saying is that firms – public or private – are sampling from an inappropriate labor pool. They are attracting workers that are too high quality, in the “overpaid” case and workers that are too low quality in the “underpaid” case.

I think that this has a hard time getting through because salaries are so riddled with moral implications. The notion that buying people is something different in degree but not in kind from buying apples is hard to swallow.

I see the same thing going on in monetary policy. Matt and Krugman have had some recent posts on how hard monetary policy is. Indeed, early in my study of economics I brushed off monetary economics as unserious because it seemed to simple. I read Walsh’s Monetary Theory and Policy and thought, is this even economics? This is like something you might give a bright twelve year old.

Yet, I there appears to be something about money qua money which makes even simple treatises difficult for folks to digest. I think its because like labor, its wrapped up with a lot of moral intuition.

From the BLS

The gasoline index declined sharply in June, falling 6.8 percent. While this decrease was the major factor in the seasonally adjusted decline in the all items index, the index for household energy declined as well. In contrast, the index for all items less food and energy increased 0.3 percent for the second consecutive month. The indexes for shelter, apparel, new vehicles, used cars and trucks, and medical care all continued to rise in June

A 0.3 percent monthly rise is an annualized rate of about 3.7% suggesting core inflation higher than the Fed’s comfort zone but well within mine. A 3.7% inflation rate would suit my ideal path of monetary policy nicely.

However, lets parse out what’s going on here. A major driver is the rise in the price of vehicles. New car price growth continued to be quite strong at .6%, while used car price growth continued to accelerate, all the way to 1.6%.

To put that in perspective 1.6% is an annualized increase of 21%. This is supports a general view that new car sales were operating well below sustainable levels over the course of the past few years. There is a lot of other data to support this, but the United States was simply building too few cars.

This is starting to show up most strongly in a shortage of used cars and hence the strong rise in price. What we expect to see is this push people into the new car market and thus increase industrial production. This is how the connection between inflation and output works in the real world.

Second we are just beginning I think to see the shelter component tick upwards. It continued to grow at 0.2% or about 2.4% annualized. This is a obviously not a big pace but shelter accounts for an enormous portion of the core CPI. Where shelter goes, so does the core.

I do expect to see this to continue to rise in the coming months as the apartment shortage begins to bite harder. This in turn will drive more construction, which may end the depression in that industry.

Bad news abounds but the fundamentals continue to move in the direction of increasing prices and output.

Looking at some data from Nate Silver, Paul Krugman concludes

What Obama has offered — and Republicans have refused to accept — is a deal in which less than 20 percent of the deficit reduction comes from new revenues. This puts him slightly to the right of the average Republican voter.

So we learn two things. First, Obama is extraordinarily eager to make concessions. Second, Republicans are incredibly unwilling to take yes for an answer — something for which progressives should be grateful.

Why exactly are we rejecting the Null Hypothesis that Obama is to the right of the average Republican voter on fiscal issues.

I can understand why both sides of the political spectrum would have an interest in painting Obama as a big lefty. What’s not as clear to me is why people believe their own propaganda.

Now, maybe lots of folks have an inside track that I am completely missing. However, there is nothing in Obama’s mannerisms, tone or statements that differentiate him from a green-eyeshade conservative.

One might be confused by the fact that he supports universal health care, progressive taxation and carbon reductions. Yet, doesn’t just about every other conservative leader in the industrialized world support these same things?

Arnold Kling has a quick, middle of the road summary of his take on the role of GSEs in the housing bubble . I feel like almost everyone has an ax to grind on this issue, and Arnold’s moderate -although not unprovocative- position is, as a result, not so commonly held, but I think quite reasonable and worth highlighting:

I feel pretty confident in arguing that Freddie and Fannie could have stopped the housing bubble by holding onto their credit standards of the early 1990’s. However, I would not be comfortable attributing their relaxation of credit standards to the affordable housing goals. I think that the management attitude toward risk changed exogenously. In part, this was due to new CEO’s with less experience in dealing with mortgage credit risk. As home prices rose, all sorts of high-risk loans performed well, and senior management misread this to indicate that it was safe to lower credit standards. Certainly, the political environment reinforced that decision. But the numerical affordable housing goals were not the dominant factor.

From the DOL

In the week ending July 9, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 405,000, a decrease of 22,000 from the previous week’s revised figure of 427,000. The 4-week moving average was 423,250, a decrease of 3,750 from the previous week’s revised average of 427,000.

Additionally it appears that 11K of those were related to the Minnesota government shut down.

Put together that makes it seem as if we have resumed the downward trajectory we had before the last few months. My working hypothesis is still that we say temporary shocks – gas prices, Japan. That are easing.

I know its sounds like a broken record but the fundamental still point to moderate and increasing growth over 2011 with an acceleration into 2012 as construction picks up.

When I taught econ 101, I would begin my semester with a discussion of auctions and the TV show “cash in the attic.” The idea was to first communicate that value doesn’t have to come from “creating” anything. It can come from rearranging the things we already have.

The items in an auction were always there but they were junk to one family and treasure to another. Rearranging the who had which item made the world a better place. This usually went over pretty well.

From there I tried to then convince them that indeed, value never comes from creating anything because everything that is, was already here. At best we can rearrange atoms into forms that are more useful to us – just like rearranging the stuff in the attic.

This was always a bit harder to get across. This video courtesy of Alex Tabarrok might have come in handy.

Jonathan Rauch, guest-blogging for Andrew Sullivan, has a bunch of stupid things to say about the blogosphere. Of course he’s being stupid on purpose, or to be more refined about it, he’s exaggerating all of his points and wording them with maximum hyperbole and provocation. His purpose here is to prove a point about the blogosphere: people get more pageviews and blog response by saying something outrageous, and that, among other things, is what leads the overall discourse in the blogosphere down the drain.

So am I proving Rauch’s point by calling attention to his hyperbolic post, or can I disprove it by reading past his provocations and purposefully rough-hewn arguments and pulling out -and refuting- his true points? Is this a test? In any case, Rauch’s core argument is wildly and obviously wrong, and it says way more about him than it does about blogs.

His first point is that “…the average quality of newspapers and (published) novels is far, far better than the average quality of blog posts (and—ugh!—comments). This is because people pay for newspapers and novels”

The average quality of blog posts, books, or any media, is relevant to the reader only to the extent that this increases the cost of finding what they read. In this way, complaining about the average quality of blogs is like a fisherman complaining about the average quality of fish in a lake rather than the quality of the fish he caught and how long it took to catch them. Also like fishing, the more time you spend reading blogs the better you get at reeling in good ones, and the less average quality matters to you. Being a clear novice, Rauch is probably pulling in a lot of small, inedible fish, and a fair share of boots. No wonder he’s mad about average quality, he has no idea what he’s doing. This he makes abundantly clear in his second point:

“If we had but world enough and time (that’s poetry, btw), we could search for good stuff all day long and the average low quality of the blogosphere might not matter. But average people on average time-budgets have to care if average quality drops, because that’s what they’re dealing with on an average day. “

The laughable idea that the way you find good blog posts is through brute force searching and spending all day says everything that needs to be said about how well Rauch understands how to consume information from blogs. One wonders if his failed attempts at becoming a daily blog reader each began by opening up Internet Explorer, directing it to Excite.com and searching for “internet blogs”.

His next point is that

“Yes, the new model is bringing a lot of new content into being. But most of it is bad. And it’s displacing a lot of better content, by destroying the business model for quality.”

I can understand why the struggle of old media companies would anger an old media journalist. But one can be furious about the impacts of the blogosphere on old media and still impartially judge the quality and utility of the of the blogosphere. Or at least one should be able to do this. Some, it seems, are unable. The idea that blogs are destroying good journalism is much more useful for understanding Rauch’s diatribe than for understanding the quality or usefulness of blogs.

To his last point:

“Yes, there’s good stuff out there. But when you find a medium in which 99 percent, or whatever, of what’s produced is bad, there is a problem with the medium.”

Again one can’t help but see the frustration of someone who has simply not mastered the form as a user. His entire position can be summed up as: “How are you supposed to work this this darned contraption?!” His opinion here has about as much merit as grandpa’s, who unable to hook up and operate the VCR proclaimed it worthless.

Alex Tabarrok argues that tax breaks aren’t government programs

People who use 529 programs and who think that they have not used a government social program are not willfully ignorant, they are demonstrating a healthy if fading appreciation of the distinction between civil society and government. What Rampell et al. implicitly imagine is that the natural state is slavery and any departure from that state a government benefit. Thus, if the government taxes your saving for a college education less than your other savings, you should be grateful for how government has benefited you and your children.

And if the government doesn’t jail you today, you should be grateful for how government has granted you the benefit of liberty.

This is the attitude of a serf not an American.

I hear this view a lot and I think its fundamentally mistaken. The question is not whether or not the government takes some seemingly affirmative action or makes a special case of refraining from action. The question is – is this program designed to cause specific deviations in behavior. Is it – as I would say – heavy touch.

Why?

Well, because through creative accounting we could simply cast all programs as some type of tax break or failure to implement policy. We could even make the transferable and there would be no discernable difference. This, however, would not make them light touch.

For example we create a refundable tax credit for certain food purchases, available to those below a given poverty line. To make it easy to implement we make this tax credit transferable. Using an EBT card, the tax payer can simply transfer his or her credit to store owner who can then apply it (refundable) against his or her own tax liability.

Now we have a tax credit program.

Similarly we could replace 529 programs with subsidies and get the same result.

In each case, the state has made a choice to influence the behavior of its citizens by manipulating their budget constraints in a particular way. That’s the essence of a government program. And, indeed its that type of intervention that displays the Fatal Conceit we should be worried about with government programs.

Lastly, to be sure – if the government explicitly chose to say, never jail top ranking civil servants for charges of assault, that would definitely count as a government program/policy and I think we could expect it to influence behavior.

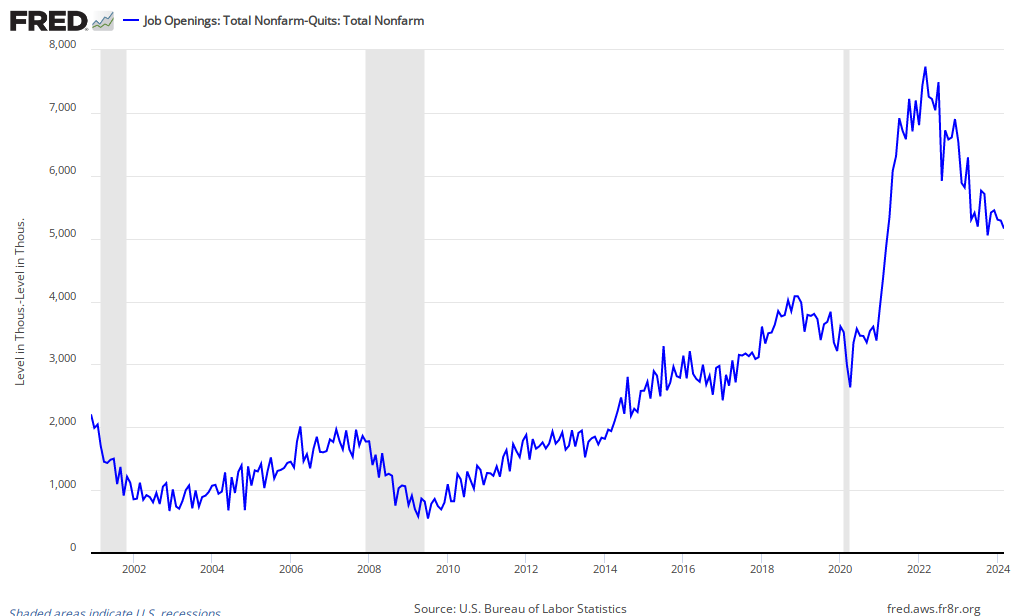

A couple quick things. One Hires were up but so where quits. Does that influence how we think about the dismal jobs report? I am not sure but its something to watch

My experimental measure: Net New Labor Demanded (Job Openings – Quits) was down, however:

I want to back up another thing that Paul Krugman said. This time about long term growth. There is a wide spread sense among public officials and even a number of economists that there are things we either can or should do to prepare set the US up for strong growth over the long term.

This isn’t a liberal or conservative thing. Yes, you here lots of conservatives talking about government spending, taxes and the like. But, you also heard the President during the townhall talk about life long education, infrastructure, etc.

Yet, either the government has been amazingly consistent in providing the right balance of these goods, or they just don’t matter that much. Because long term growth has been incredibly consistent, even including the Great Depression and WWII.

Here is the real US GDP on a log scale (straight lines are constant growth rates)

Though the Great Depression was horrible at the time after it and the War time bounce back were over the economy simply resumed the same path as if nothing had happened. Great Depression. Massive World War. The New Deal. The coming of the income tax and then the raising of it to stratospheric rates. The rise of labor and fall of organized labor. Entry of women in the work force.

All of it and you can barely see a dent. Some one has probably addressed this in the economic literature but from what I can tell GDP growth is steadier than GDP per capita growth and much steadier than GDP per worker growth. That’s deeply fascinating.

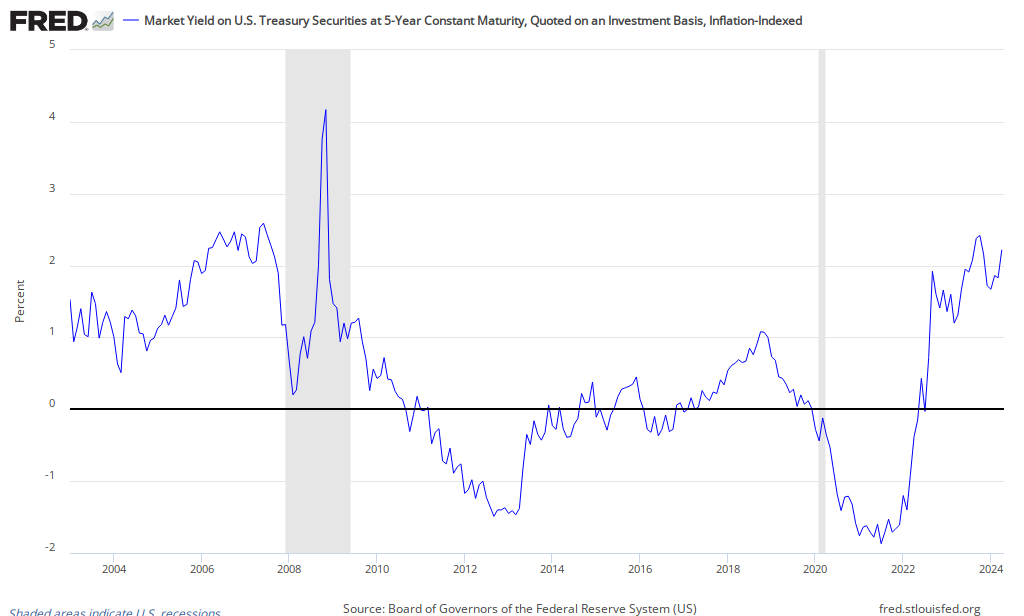

Paul Krugman points out again that interest rates have failed to rise despite heavy borrowing by the Treasury. He uses nominal rates but I think the point is better made using real rates and bar graph.

What this highlights is that real rate of return on government 5 year government securities is now negative. You want to stop and absorb that because I think it’s a bigger deal than most people realize.

Suppose the government had two choices. It could either pay for infrastructure improvements as it went along out of tax revenue or it could borrow money build the infrastructure now and then repay the money with tax revenues.

Ordinarily the question would be, does the advantage of building quickly outweigh the cost of the interest.

However, right now the interest cost is negative. The government saves money by borrowing now rather than waiting and paying cash. Let me say again because I have noticed that this goes against so much intuition that its hard for many people to wrap around when I first say it.

The government will wind up paying more if it decides to pay cash for a project than it will if it decides to borrow. This is irrespective of the return on the project itself or the advantages of avoiding delays or anything like that. It is simply that the cost of borrowing is negative.

It is cheaper than paying cash.

As I always I struggle between my desire to push what I think are important points to my overwhelmingly well informed readership and my basic belief that there are some conversations that should not be had in public.

I understand that the conversation is being had whether I approve of it or not. Nonetheless, participating is an issue of personal ethics I haven’t completely worked out.

In the past I’ve chosen obtuseness as the middle path. I’ll stick with that for now.

For those inclined to look Professor Kramer of Brown University has a take in a major daily that mirrors much of my own on the issue. Indeed, the problem of improperly selecting test subjects is likely responsible for the general rise in "relative ineffectiveness” we see across the drug spectrum.

In any case, I think the attention this issue gets in terms of medical funding and research is vastly inadequate relative to issues like cancer and heart disease. The landscape is too dominated by folks with strong opinions and axes to grind. While the issue itself is frankly more important than bodily health.

To update C.S. Lewis, you don’t have a mental state. You are a mental state. You have a body.

So I want to make this post as gentle as possible but it touches issues that are for some reason quite emotional with me. I feel the call of the shrill.

The more I here people talk about the issues surrounding first the financial crises, inflation and now the debt ceiling the more it makes sense to me why Wall Street pays such enormously high salaries.

For example, there is this meme going around in reference to the debt ceiling were folks are asking rhetorically: If you keep hitting your credit card limit should you always raise you limit?

Is this a serious question? Of course you should always raise your limit. If the Red Sox win the World Series you should raise your limit. If you dog takes a poop in the park you should raise your limit. If it rains on Tuesday in July you should raise your limit.

Why?

Because you should always raise your limit. The whole point of the limit is to protect the creditor against you. If he willing to forgo that, take it.

Trying to play games with your credit score aside, it is always but always better to have more liquidity than less.

It is always but always better to be playing with or have the potential to play with someone else’s money. It is always but always better to have more credit and to be more heavily leveraged.

The only question is the price you have to pay. The carry and the exposure. However, the carry on a limit raise is zero, there is no exposure and the asset is pure liquid. You always take free liquidity.

Imagining a friend of mine saying, “Hey I was just offered a bunch of liquidity at zero carry, should I take it?” is like having a single male friend ask me, “Hey Monica Bellucci just asked me to spend the weekend in Aspen with her, should I take it?”

Well, are you a crazy person? Do you make it habit of throwing away option value and weekends with iconicly beautiful women?

Maybe some people do.

Maybe some people do.

From the early days of the internet I always saw the goal as a type of virtual reality that allowed the agglomeration effect of cities to be felt on a global scale. For a heavy reader and lifetime hater of synchronous communication, like myself, even the old newsgroups and bulletin boards gave that feel. Obviously, however, they were the geek niche’s of geek niches.

The World Wide Web opened things up in a revolutionary way. However, its still didn’t quite seem to do it. The relationships that are so central to what human being are and what we as a species can do were missing.

Enter social media. Facebook bridged a lot of that gap, creating a space that map tightly enough to real world social networks that true friendships could be forged.

There are people I know on Facebook whom I have never spoken to in real life, much less been in the same physical room. There are some whom I knew primarily through social media and then finally meeting them in real life was seamless. They were exactly who I imagined them to be.

And of course, there are old friends with whom Facebook keeps the relationship alive and fresh.

One place where Facebook just doesn’t seem to work at all is working relationships. Those are still dominated by physical meetings, emails and interestingly enough, Gchat.

In part this is because, like most people I am reluctant to friend folks with whom I have a purely working relationship. Strangers I don’t mind at all. But, people who address me as Professor Smith, that’s a bit of a different matter.

The circles and the twitter like nature of Google+ helps with that significantly. The whole world can follow you public persona. Your colleagues your work persona and your friends can see the part of you that makes the word “friend” special.

Perhaps just as importantly its completely integrated into your work environment. For many people “going to work” starts with opening Microsoft Outlook. Your day is defined around your meetings and your email. Much of the rest of what you do probably is accomplished with a web browser, Excel, Powerpoint, Word and some specialty program related to your exact job.

From all of that Facebook is a distraction. You go to Facebook and away from work. With Google+ its built in. The black bar ties it all together. I can’t quite explain why that seems to make a difference but it seems to make all the difference in the world. Something about switching mental modes perhaps.

But, just as it made sense to Gchat a colleague about something from your email but not as much sense to Facebook message them, it seems much more natural to invite a few coworkers to an impromptu hangout – Google+’s group video chat – to discuss an idea than to Skype them.

This brings the concept of the virtual office much closer to reality.

David Brooks recent piece on Diane Ravitch has lead the New York Times to have Ravitch engage in a “Sunday Dialogue” where she answers reader questions. Whitney Tilson, a frequent Ravitch critic, writes in with a common complaint:

…while it’s very clear what Ms. Ravitch is against (she’s a vocal, clever and, sadly, effective critic of what we reformers are doing), I can’t for the life of me figure out she’sfor.

Saying you want a good teacher in every classroom and a well-rounded, rigorous curriculum is as trite as saying you’re for motherhood and apple pie. What would Ms. Ravitch say to John White and Cami Anderson, who just took over two of the toughest school systems in America, in New Orleans and Newark? What would be the top three to five things Ms. Ravitch would have them do in their first year?

There are two parts to Ravitch’s reply that are relevant, one addresses all of her correspondents, and the other addressed to Tilson specifically. I don’t think her response does much to defend herself against Whitney’s charges:

Good schools are no mystery. They have a dedicated principal, a stable staff with a mix of veterans and young teachers, and a strong curriculum that includes not only basic skills but the arts, history, civics, science, world languages, literature and physical education. And they engage parents and community leaders to support their goals….

To Mr. Tilson: Why expect schools alone to close achievement gaps that begin at birth, when those gaps can be prevented in the first place? Decades of research by the Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman and others have found that early intervention is the single most effective policy we can invest in. Start with prenatal care. Teach new mothers how to help themselves and their children. Add a strong pre-kindergarten program so that children start school ready to learn.

Pivoting off Karl’s recent posts, I want to throw my two cents in on the minimum wage. Actually, I’ll make that one cent, because I’ve already written about my take on the empirical evidence plenty before and there’s no sense in rehashing that. What I do want to draw attention to is a smart post by Robert Waldmann from 2009 that illustrates why now in particular is a bad time for the minimum wage:

Empirical estimates of the effect of the minimum wage on employment suggest that the effect is very small. One famous study by Card and Krueger showed a positive effect of an increase in the minimum wage. The logic used by Card and Krueger to understand how this could happen suggests that things are different now.

Their logic is basically that firms can choose to pay a low wage and have a high quit rate and take a long time to fill vacancies or pay a high wage and have fewer quits and fill vacancies more quickly. If they are forced to pay the higher wage, their desired level of employment will be lower, but that level is the sum of employment plus vacant jobs. A binding minimum wage can reduce the number of vacant jobs by more than it reduces the sum of employment plus vacant jobs. Thus more employment.

I think this is not relevant to the current situation. There are very few vacant jobs. Quit rates are low. According to their logic, the effect of the minimum wage on employment depends on the unemployment rate. The evidence of a small effect is almost all from periods of unemployment far below 10%. I don’t think it is relevant to the current situation.

As you can see in this graph quits are still quite low, and so Robert’s logic still holds.

It’s always worth noting that when basic laws of supply and demand don’t seem to hold it’s not because of some universal and eternal forcefield simply protecting a market from these laws, but for reasons typically explained by some usually more complicated economic theory. Either that or it’s a mystery, and maybe the exception to the rule is simply due to some irreducible complexity economists will never grasp. But if this is the case it should make you worry even more: since you don’t know where the exception is coming from, you have no idea what will cause it to give way.

When the laws of supply and demand seem violated, it’s probably for a reason, and that reason may not hold in all circumstances. “When and under what circumstances will the result you believe continue to hold?” is an important question to ask yourself. Take the minimum wage. I don’t know any economist who believes that the minimum wage won’t definitely cause unemployment at some level. Maybe it’s a $10 minimum wage, maybe it’s $8, and just maybe it varies a lot by location, industry, and job. That some studies in the past have failed to show a significant unemployment effect of the minimum wage should not lead you to toss aside the concepts of supply and demand and conclude that they are meaningless or disproven in this context.

Sometimes in debates with my more conservative friends they confuse my enthusiasm for redistribution with a distrust of capitalism or an inherent uneasiness with inequality.

Neither of those things are true. I am a lover of the free market. I find stories of self made billionaires inspiring. I see the emergent order of the market beautiful. Indeed, though I am not a Randian, I find her romantic portrayal of egoist heroes touching in a way that fiction rarely is for me.

What pulls me back towards redistribution is an acknowledgement of the pain that accompanies economic hardship. Mike Konczal called this pity charity liberalism and perhaps it is. However, pity for the suffering of mankind is nothing to be ashamed of.

Matt Yglesias draws us to a Gallup chart show what a difference economic hardship can wrought

Losing your job is on par with losing your marriage in terms of life satisfaction. Being poor doesn’t trail far behind. These are tragedies of human suffering and they deserve our attention.

Kevin Drum doesn’t like my take on the minimum wage

This kind of stuff bothers me on a bunch of different levels. Let’s count the ways:

- You either believe empirical studies or you don’t. If you have reason not to believe them, then let’s hear it.

- Intuition about supply and demand just flatly won’t work in this case. We’re talking about a market with (probably) low elasticities and a huge number of confounding factors that could push it in multiple directions. It’s easy to see that a small increase in the minimum wage could be overwhelmed by other factors and lead to either a very small or zero impact on employment levels.

- Are there jobs where it’s profitable to hire at $4.75 but not at $7.25? Well, there must be some, but we’re talking about such low skill levels here that there very well might not be many. That’s why empirical studies are so important. The effects are just too small to intuit.

- Is this really what we’ve come to? That we should provide a (probably very small) boost to the job market by allowing businesses to hire people for $9,500 per year instead of $14,500? Seriously? I mean, this is the ultimate safety net program, aimed squarely at working people at the very bottom of the income ladder. If we’re willing to throw them under the bus, who aren’t we willing to throw under the bus?

This is how I think the honest intellectual response goes: Basic economic reasoning tells me that the minimum wage cuts employment and that the more effective the minimum wage is in raising wages above market rates the more pronounced the effect will be. For years empirical studies seem to support this though I do not have deep knowledge of them.

Then David Card and Alan Krueger come out with a study showing the opposite. This had an impact on me primarily because the names Card and Krueger were attached to the study. They are smart, thorough guys and quite frankly that matters. Yet, I haven’t delved seriously into the empirical issues surrounding it.

I am aware of some of the common faults that people point out from the Card and Krueger work, but I haven’t really evaluated them carefully either. I could latch on to some of those criticisms as my “reasoning.” But, honestly they are not my reasoning.

My reasoning is that I had strong priors one way. I saw conflicting evidence that made me question those priors but that evidence wasn’t strong enough to completely persuade me.

Its also true that while my skepticism is a data point, people should keep in mind that it doesn’t carry a huge amount of weight because I don’t have a huge amount of evidence behind it.

There has also been some follow-up work that has confirmed Card and Krueger. My understanding is there has also been work to refute it. I read a well put together paper not long ago using border-states that seemed to show small effects but my impression at the time was that the variables of true interest were going in the expected direction, less than expected employment growth.

I stir all of that together with my causal empiricism about how businesses work and I come to the conclusion that “my best guess is that the minimum wage decreases employment opportunity for low skilled workers.”

My mind could clearly be changed on this but that’s where I am right now. Not to turn this into to much of a philosophy of science post, but I think there is too much hanging of hats on specific arguments, weaknesses in position, or points about analysis.

That’s not how we reason and that’s not how a good Bayesian should reason. All evidence “counts” just to varying degrees and priors matter. We shouldn’t pretend that unless we can find specific reasons to tear apart a study we have to accept it. Doing that just motivates us to be artificially critical.

We accumulate evidence over time and hopefully get closer and closer to the truth.

Arnold Kling talks about Patterns of Sustainable Specialization and Trade. Richard Florida has made note of the Great Reset. Tyler Cowen has highlighted zero marginal product workers.

When I dig through the data is hard to see evidence that some major technology induced changed has suddenly come upon the United States. The basic globalization factors that have been present for the last two decades are still with us, that’s true.

As I frequently try to mention, construction is in an inexplicable depression. Its extremely bad on a scale that is wholly underappreciated by the media at large. Its also a pattern that quite simply can’t be sustainable, doesn’t represent any imaginable reset in US living patterns and would seem to have very high marginal product moving forward.

However, there is interestingly enough one sector where these notions make a lot of sense: government. Here is growth in government employment since 1980. I include that to show the impact of the Reagan Revolution.

You see a sharper and harder decline than at any point since 1980 unless there is a dramatic turnaround soon this will beat out the 1980s in terms of government job losses.

For transparency let me show you government employment as a percentage of all employment, though I think the graph hides a larger point.

The swings, including the latest upswing are largely due to changes in the denominator. That is overall employment is more volatile than government employment. So here is government employment as a fraction of the civilian, over 16, non-institutionalized population. That is, people who could legally have a full time job.

From the peak just after the 2000 recession until now, we are looking at a drop approaching 1%. That is, at the peak nearly 10% of all legal working age Americans worked for the government. Now, its closing on 9%.

That may not sound like a huge drop but there are roughly 240M legal working age Americans, so that’s closing in on 2.4M government jobs that are not there.

Now we could see a dramatic bounce back as we did in the 1980s. However, I don’t see the seeds of that. The biggest structural change in the US economy looks to be away from government employment.

Just shockingly bad on every dimension I have glanced at.

- Private payrolls up olny 54K.

- Government down 39K.

- Government cut at all levels.

- Construction down

- Manufacturing flat

- Retail flat

- Financial Activities down

- Education and Health flat – yes flat

- Utilities flat

- Information flat

- Wholesale Trade up a smidge

The only bright spots where professional and technical employment growing at 24K and Leisure and Hospitality growing at 34K. Though a surprising amount of the latter looks to be gambling.

I’ll sift through and maybe have more later

If you’ll allow me to engage in some rather speculative predictions about the future, I have a vision I’d like to sketch out (for some reason) about what fast food service will look like in the not-so-distant future. The short of it is, smartphones will automatically place an order and pay for it for people on their way to work, school, or other routine destinations.

In large part, the necessary tech is already here. The payments system is obvious, as you can already buy apps and songs on your phone. The other main part is right around the corner, as Apple’s upcoming iOS5 will provide location based reminders that deliver a preprogrammed message when you are near a certain location. For instance, you can tell it to remind you to buy milk when your phone detects that you are in the grocery store. The only change I’m proposing is that reminders should be directed outward, to the retailers you are heading to.

This means that Dunkin Donuts will know when you are five minutes away, and will receive your order, all without you having to do anything. Then when you walk in to the store you pull up your Dunkin Donuts app, wave the barcode in front of a scanner, and the worker (or machine) will give you your order. The app could be time and date specific as well, so it won’t order unless you are five minutes from the Dunkin Donuts, and it’s a weekday, and it’s around 8am.

An even simpler version of this allows you to order on your smartphone before you leave the house, with the phone telling the store how long it will take you to get there, and therefore when they should start cooking. Think of this as taking the MTO machines in many food places and simply putting it in the smartphone. It’s easy to imagine how this future of retail could cut down on the number of retail food workers by 15% or even more.