You are currently browsing the monthly archive for June 2011.

Arnold Kling David Henderson revisits his claim that Social Security and Medicare are Ponzi schemes based on a comment by John Seater. John’s point was that Ponzi schemes are necessarily insolvent while Social Security would be solvent if the population was growing fast enough.

Arnold David replies:

It’s not necessarily the case that Ponzi schemes must circle around to the original people who invested in them. If the scheme offered modest enough returns and spread slowly, it could last forever in a country with a growing population. Therefore, Ponzi schemes, contra Seater, could remain solvent.

This actually brings to mind a point much deeper than the Social Security debate; a point that may be fundamental to intellectual disagreement in policy circles.

Arnold is using the term Ponzi scheme and I am certain that he feels its appropriate and meaningful. Yet, as best as I can tell he is stripping of its primary connotation: necessary insolvency and bankruptcy for the participants.

It is tempting at this point to say that Arnold is being “dishonest” about Ponzi schemes and Social Security. This is where lots of intellectual discussion go off the rails/

However, I don’t think “dishonesty” is accurate in the traditional sense. I think Arnold means what he says and is communicating in good faith. Leverage the negative affect of the term Ponzi scheme seems appropriate to him because Social Security and Medicare likewise leave him with negative affect. I am assuming because no investment is induced by the system even though its made to look like a savings system.

Yet the term Ponzi scheme leaves most people with negative affect for entirely different reasons. For most people, the negativity comes from the fact that you cannot win and sooner or later the entire thing must come crashing down.

My points in all of this are several

- This type of cross-talk happens all of the time in intellectual disputes and is responsible for a good portion of the disagreement that we think we are having.

- Though it can easily escalate to attacks on intellectual honesty there is no bad faith on anyone’s part

- It can be cut through with careful and calm reasoning. This is hard to achieve but we should strive for it.

Bloomberg reports on Alabama’s recent immigration crackdown:

When Tuscaloosa, Alabama, begins rebuilding more than 7,200 homes and businesses leveled by an April 27 tornado, it may find itself missing a workforce capable of putting the city together again… Tuscaloosa County’s 6,000-strong Hispanic population –including roofers, Sheetrockers, concrete pourers, framers, landscapers and laborers — is disappearing, he said, before a law cracking down on illegal immigrants takes effect.

The obvious question to ask is whether there be others who step in to take the jobs these immigrants would have taken at the wage that will be offered. This question, which I go into detail on here, does ignore one crucial aspect of the problem. The cost to employers is not simply higher wages per hour, but higher unit labor costs. That is, for a given unit of value-added output, what happens to the total cost of labor? Wages may only need to go up by 10% in order to find workers willing to replace illegal immigrants, but if the quality of work goes down -if the workers are slower, sloppier, etc.- then unit labor costs may double or more.

You can see this implied in the Bloomsberg article where a contractor says “It’s not the pay rate. It’s the fact that they work harder than anyone. It’s the work ethic.”

The lesson can be seen in Georgia’s attempt to replace illegal immigrants with probationers:

For more than a week, the state’s probation officers have encouraged their unemployed offenders to consider taking field jobs. While most offenders are required to work while on probation, statistics show they have a hard time finding jobs. Georgia’s unemployment rate is nearly 10 percent, but correction officials say among the state’s 103,000 probationers, it’s about 15 percent. Still, offenders can turn down jobs they consider unsuitable, and harvesting is physically demanding.

The first batch of probationers started work last week at a farm owned by Dick Minor, president of the Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association. In the coming days, more farmers could join the program.

So far, the experiment at Minor’s farm is yielding mixed results. On the first two days, all the probationers quit by mid-afternoon, said Mendez, one of two crew leaders at Minor’s farm.

“Those guys out here weren’t out there 30 minutes and they got the bucket and just threw them in the air and say, ‘Bonk this, I ain’t with this, I can’t do this,'” said Jermond Powell, a 33-year-old probationer. “They just left, took off across the field walking.”

Mendez put the probationers to the test last Wednesday, assigning them to fill one truck and a Latino crew to a second truck. The Latinos picked six truckloads of cucumbers compared to one truckload and four bins for the probationers.

This isn’t a knock on the probationers. Despite being labeled “unskilled” work, this is clearly an extremely difficult job that even healthy, able-bodied adults can’t just pick up and do. Yes, for a high enough price the probationers can probably be induced to stay out in the fields all day. But with wages moving up at the same time productivity is moving downward, it’s not hard to see how employers of illegal immigration might be forced to close up shop as business becomes unprofitable.

So remember this when you read about low-paying jobs illegal immigrants are doing and people tell you that high school students or the unemployed would do them for a couple dollars an hour more: it is not hourly wages that matter, it’s wages per value added output.

From Reuters

Rubin said the Android week-by-week growth rate is currently at 4.4 percent but he did not disclose, in his Tuesday announcement on Twitter, how many of the devices being activated are smart phones and how many are tablet computers, a relatively new competitive battleground in wireless devices.

File this under: nothing happens, until it all happens at once. When the Palm introduced the Treo and the first Windows Tablet’s came out around 2000 I thought we had entered a new phase in mobile tech.

There was nothing but crickets for about a decade and then overnight smartphones and tablets are everywhere.

I have repeatedly questioned the value of screening, particularly cancer screening in extending life. I am, predictably, mildly annoyed by the term “preventing death”, since death is unpreventable.

Regardless, a new Swedish study pushes back on my assertions

The study of 130,000 women in two communities in Sweden showed 30 percent fewer women in the screening group died of breast cancer and that this effect persisted year after year.

Now, 29 years after the study began, the researchers found that the number of women saved from breast cancer goes up with each year of screening.

"We’ve found that the longer we look, the more lives are saved," Professor Stephen Duffy of Queen Mary, University of London, whose study was published in the journal Radiology, said in a statement.

In Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation, he points to three main types of low-hanging fruit that helped drive America’s earlier economic growth but are now drying up:

In a figurative sense, the American economy has enjoyed lots of low-hanging fruit since at least the seventeenth century, whether it be free land, lots of immigrant labor, or powerful new technologies. Yet during the last forty years, that low-hanging fruit started disappearing, and we started pretending it was still there.

Yet while real limiting factors may have caused free land and powerful new technologies to start disappearing over the past 40 years, the only thing that has made “lots of immigrant labor” go away is our political choice to let in less immigrants. I think Tyler is wrong to largely neglect more and better immigration as a way to reverse our Great Stagnation. One could argue that changing opinions about immigration is very difficult, but so too is his crusade to raise the status of scientists, one of his main recommendations for stagnation reversal. Read this quote from his book, for instance, and you decide whether it could just as easily apply to immigration:

That’s going to be hard to achieve, but it’s not a question of lacking the resources. We simply need to will it, and change our collective attitudes, for it to happen. It’s a potential free lunch sitting right in front of us.

I’ve sort of made this point somewhat before, but I think it bears repeating, especially given our current political debates. If Tyler is right, and lots of immigrant labor was one of the most important drivers of our early growth, and a crucial low-hanging fruit, then our subsequent Great Stagnation should be regarded, at least in part, as a choice.

Tim Slekar at the Huffington Post tries to give readers a lecture in “stats 101” and ends up making an elementary error himself. Tim writes:

For those that forgot stat 101, correlation does not mean causation. Example: If you take a sample of people involved in automobile accidents on their way to work and ask the sample if they had breakfast and then checked the correlation between eating breakfast and automobile accidents — it would be through the roof. But what does this mean? Nothing from a cause and effect stand point. Eating breakfast does not cause car accidents — period. Remember, correlation does not mean causation. However, this simple statistical rule doesn’t seem to matter to the reformers.

If you took a sample of people involved in accidents and looked at the correlation between eating breakfast and being in an accident it wouldn’t be “through the roof”, it would be undefined. Let X be a dummy variable being 1 if someone ate breakfast and 0 if they didn’t, and let Y be a dummy variable equal to 1 if someone is involved in an accident, and 0 if they weren’t. A dataset like Tim is talking about might look like this:

X ,Y

1,1

0,1

1,1

0,1

0,1

1,1

1,1

1,1

1,1

Notice that all of the Ys are equal to one, because Tim said we are sampling people who have been involved in an accident. The problem is, as they teach you in stats 101, the formula for correlation is cov(X,Y)/std_dev(X)*std_dev(Y), where cov is covariance, and std_dev is the standard deviation. The standard deviation of a number that is always equal to 1 is zero. And so the correlation has a zero in the denominator, which is undefined, not “through the roof”.

Reihan Salam and Tim Lee have written very thoughtful posts on immigration and the whether and why that affects our the size of our collective economic pie.

Reihan defends the fixed-pie model of the economy that conservatives elsewhere reject, which Tim levels as evidence of conservative hypocrisy. If I could try and summarize Reihan’s position very succinctly, it would be that at some level, pies become fixed. Put into economics-speak, in many systems, including our economy, and it’s various micro-economies, at some scale returns diminish, and then they become negative.

I think Matt Yglesias and others might point to Manhattan and Honk Kong with their 10,000+ people per square feet and argue that we are nowhere near negative returns in the country as a whole. But Reihan, I’m guessing, would argue that Manhattan did not get to it’s level of density over night, and that it is the sustainable flow, not the sustainable level, that he is worried we would go over. In terms of what the costs, or losses the country would suffer by going “too fast” with immigration, I think Reihan lays it out nicely:

“There are, however, congestion and other costs associated with an increase in the size of the population, which vary according to the demographic characteristics of the population. Given that the United States is a mixed economy in which we devote a large share of public resources to educating children, incarcerating criminal offenders, providing health services to the indigent, etc., one can raise legitimate questions about what constitutes an economically sustainable population influx consistent with maintaining public institutions in some recognizable form.”

There are two important points to make here, one about skilled immigration, and one about immigration overall. Let me start with the latter. Unlike the more open borders people, I tend to worry that at some level of immigration, some of our cultural, legal, and economic institutions might give. I know that’s sort of a mushy and imprecise claim, and it’s not satisfying to keep millions of people from drastically improving their lives for the sake of mushy and imprecise ideas, but I think part of the reason that this country is capable of improving lives so greatly, and is such a beacon and desirable destination to so many people is precisely because of the cultural, legal, and economic institutions we have here.

My concerns about borders that open up too much or too fast is both that these institutions degrade, and that Americans will react to the degradation of these institutions by choosing to close the doors even more drastically than they are now. We are a democracy after all, and that is part of the draw of this place. This is why I propose a gradual opening of the gates, and moving them farther and farther open. To me the degradation of institutions is purely speculation at this point: America is not suffering from a blight of immigrants. At current margins I believe both skilled and unskilled immigrants are a net plus, and at the very least I think we can all agree they are no serious threat to our institutions. We’ve got an amazing, powerful, engine for freedom and wealth here, and we’re driving her around at 15 mph because we’re worried that the engine might blow out at 100 mph. Let’s open her up slowly and see what she can handle, because it’s certainly more than this.

The second point I want to make is about skilled immigration. All the reasons that Reihan argues that the pie is fixed at some level do not apply to high-skilled, english speaking immigrants. In fact the more skilled immigrants we let in the farther we can go before we encounter fixed-pieism. In other words, skilled enlglish immigrants provide us with more tax money to support the government part of our mixed economy, and they tend to not go to jail, and they tend to provide educated well-behaved children to our school systems. They grow the pie. Jose Vargas is a perfect example. He is a force that strengthens, not stretches, our institutions. If a fixed pie is what we are worried about with respect to immigration, then we need to divide the conversation into two pieces: skilled and unskilled immigrants.

A final thing I’d like to address is Reihan’s response to a comparison from Tim Lee. First, here is Tim:

Entering the country without government permission is illegal, and probably should be so. The federal government has any number of powers to enforce the law, including refusing to let you cross the border (leave the airport, etc), investigating over-stayed visas, limiting access to driver’s licenses, auditing employers, deporting people, and so forth. Objecting to any particular immigration enforcement mechanism isn’t the same thing as objecting to immigration regulations altogether. It’s perfectly coherent to say that the government should make a reasonable effort to prevent people from moving here illegally, but that certain types of particularly invasive enforcement methods (like employer verification) should be off the table. This is just how our legal system works.

But I also think speeding cameras are a bad idea because I sometimes think the posted speed limit is too low and I like the fact that I can ignore it and (mostly) not get caught. Similarly, our copyright laws are too strict; it’s a good thing that people can sometimes share content in circumstances that a strict reading of the law wouldn’t allow. In other words, the fact that people can mostly get away with breaking certain laws is a feature, not a bug, of our legal system. It provides a “safety valve” that ensures that stupid legislation doesn’t do too much damage.

The same point applies to immigration law. Obviously, we ought to enact sane immigration laws that make it easy for people like Jose Vargas to get a green card. But given that we haven’t done that, it’s a good thing—both for him and for the rest of us—that our enforcement system wasn’t effective enough to prevent him from taking a job here.

Again, there’s a huge double standard here. We American citizens take a strictly moralistic tone toward laws that we don’t personally have to follow. But “the rule of law” goes out the window when it comes to that pot you smoked in college, or the use taxes you haven’t paid on your Amazon purchases, or those pirated MP3s on your hard drive. When we’re talking about laws that actually affect us, we’re glad there’s some breathing room between the law on the books and what people actually get punished for.

And here is Reihan:

“When we violate copyright laws or when the authorities are lax in enforcing the speed limit, we don’t create a situation in which people are forced to lead a shadow life that will contribute to larger social problems. These infractions are of a fundamentally different kind. Now, one might object that we could then just give said people in the shadows a path to citizenship, thus solving the problem. But this would mean ceding authority over our immigration laws to those who are willing to break them.”

I think Tim is exactly right, and I don’t think these are as different as Reihan suggests. When we violate the speed limit we are potentially putting people at risk. When we violate copyright laws we are potentially discouraging those artists, or other artists, from creating more output in the future that we would all benefit from. When an illegal immigrant comes here they are *potentially* contributing to larger social problems. In each of these cases there is a risk, but not a certainty, of imposing costs on someone else. In the case of Jose Vargas, the man was clearly reducing social problems through his excellent writing.

The “shadow life” part seems like a cost born strictly by the immigrant, and I’d leave it to them to decide whether their lives were improved by coming or not, and staying or leaving. But I’m not sure if living in the shadows is a cost to the immigrants is a claim Reihan was actually trying to make, or if he simply meant the shadow life is what is contributing to larger social problems. If it’s the latter I’d be interested in some more elaboration here as to what the shadow life is and how it contributes to larger social problems.

Unsurprisingly from Reihan and Tim, I find this disagreements clarifying and thought provoking, and I’m glad to be seeing this exchange.

Everyone is talking today about Jose Antonio Vargas, the illegal immigrant who told his story recently in the New York Times. Dan Foster, at National Review, has sympathy for Jose the child who had little choice in becoming an illegal immigrant, but not for Jose the adult who chose to commit further illegalities in order to remain here:

The first part of Vargas’ story — a kid living and loving America for years before his shocking discovery that he has been made complicit in a crime — does indeed elicit sympathy. It’s stories like these that make me open, at least in principle, to something like a narrowly-tailored version of the “DREAM” Act. But the second part of his story, in which a fear- and shame-driven Vargas, with the aid of his family, perpetuated and compounded those crimes (Vargas eventually got around to what you might redundantly call fraudulent tax fraud, repeatedly reporting himself as a citizen rather than a “permanent resident”, when in fact he was neither), elicits from me nothing like the outpouring of support Vargas is already enjoying on the Left.

Punishing a minor by removing him from the culture he’s adopted as his own, for the crimes of his parents, does strike me as fundamentally unfair. But what liberals leave out of this story, time and again, is a competing — and in my view overriding — unfairness. Reihan has argued repeatedly, and effectively, that we should treat access to the U.S. economy, not to mention its extensive welfare state, as a scarce resource. We can debate and debate the best way of distributing this resource– from “not at all” to “come one, come all” and everywhere in between. But distributing it based on who manages most successfully to violate the law, at the expense of would-be immigrants who are honoring the process, is surely not a valid option.

Foster’s argument seems to be that it would be unfair to deport a minor who has little or no choice in the matter, but once that minor turns 18 the illegality is their choice, and it is no longer unfair to deport them. This is why he has pity for Jose the child, but the story of Jose the adult “elicits” from him “nothing like the outpouring of support Vargas is already enjoying on the Left”.

My question for Daniel is this: if he were in Jose Vargas position, what would he have done? Upon turning 18 would he have left this country and returned to the Philippines because it would be unfair for him to stay? Would he have sacrificed the life he knew here out of a sense of unfairness to other potential immigrants we aren’t letting in? Would he agree that the government should deport him?

I don’t think it is wrong for Jose Vargas to do what he could to stay in this country and keep the life he knew. I think Jose Vargas, and many of those who have risked much to be here, are the kind of people who would be alloted citizenship in an ideal and ethical system. He has the willingness and the ability to pay his way in any fair immigration scheme. He’s a net positive in our society. How many millions of immigrants a year are we away from a system where we have to tell highly skilled, highly educated people who believed themselves to be American that we are too full? I don’t think we will ever be that full, and we certainly aren’t now.

Until we get a fair immigration system, the way to get a fair result is for people who would have gotten here under the fair system to sneak in, and break the rules, and do what they can to stay.

In another, perhaps too quick and dirty for the Atlantic, let me respond to this by Robin Hanson.

We all want the things around us to be better. Yet today billions struggle year after year to make just a few things a bit better. But what if our meagre success was because we just didn’t have the right grand unified theory of betterness? What if someone someday discovered the basics of such a theory? Well then this person might use his basic betterness theory to make himself better in health, wealth, sexiness, organization, work ethic, etc. More important, that might help him make his betterness theory even better.

After several iterations this better person might have a much better betterness theory. Then he might quickly make everything around him much better. Not just better looking hair, better jokes, or better sleep. He might start a better business, and get better at getting investors to invest, customers to buy, and employees to work. Or he might focus on making better investments. Or he might run for office and get better at getting elected, and then make his city or nation run better. Or he might create a better weapon, revolution, or army, to conquer any who oppose him.

. . .

All of which is to say that fearing that a new grand unified theory of intelligence will let one machine suddenly take over the world isn’t that different from fearing that a grand unified theory of betterness will let one better person suddenly take over the world. This isn’t to say that such an thing is impossible, but rather that we’d sure want some clearer indications that such a theory even exists before taking such a fear especially seriously

I don’t think a betterness explosion is that far fetched of a concept. Indeed, we are in the middle of one right now. It’s the sustained period of economic growth after the industrial revolution.

The important concept – to my mind – is that this betterness revolution is ultimately limited by our ability to analysis and communicate information. There are various means we might think of for this process to change radically and with it the nature of the betterness revolution.

For various reasons the grand unified theory of betterness seems illusive. But the betterness box does not. Suppose that we EM a single smart person few thousand times, put all the EMs into one box and then turn up the speed 1 million times.

Could not the box conceivably design better faster boxes to put itself into, continuing a rapid betterness explosion? Would it not look to the rest of the world as if that single individual just “took over”

Arnold Kling writes

Yes, there is technological unemployment. Russ [Roberts] continues,

Somehow, new jobs get created to replace the old ones. Despite losing millions of jobs to technology and to trade, even in a recession we have more total jobs than we did when the steel and auto and telephone and food industries had a lot more workers and a lot fewer machines.

Re-reading the first sentence, with its passive voice, I can almost feel his hands waving. The PSST story is that entrepreneurs must figure out how to reallocate resources when productivity rises faster than demand in some industries. I want to suggest that it can be a very difficult process. As labor gets more specialized and production processes become more roundabout, large adjustments require more steps.

Here is the core issue in my mind: why isn’t this process made simple by price adjustments. Its clear that it might be difficult to find a way to utilize labor that was just as productive as the method used before technological innovation.

However, if the wage falls low enough then there should be lots of value add that could be done.

Taking this to the extreme makes this point clear.

Suppose that Michigan autoworkers lost their jobs and their wages fell to One Cent per Year. Well at One Cent per Year I could hire armies of men to scrub my house by hand, to take out the garbage, to walk behind me recording every thought I had and double checking that every appointment was made and kept.

At one cent per year there are millions of extremely easy uses and worthwhile uses for labor.

If we accept that the labor market would clear at One Cent Per Year. Then the question is why has the labor market not cleared while at the same time the wage has not dropped to One Cent Per Year.

There are lots of reasons why we can think that this hasn’t happened but this is – at least in my mind – the central question. We know that we can profitably employ everyone in America at some wage. So why is there a prevailing wage at which people are not employed?

Over at The Atlantic today…

- Karl presses the question of whether there are too many homes in America

- Niklas argues that Keynes’ only useful insight was extreme liquidity preference, and calls Krugman “as close to a modern-day Keynes as anyone could ask for”

- I discuss how an illegal immigrant crackdown is impacting farmers in Georgia. Yesterday I talked about how house price declines are affecting divorce rates.

We’ll probably be slightly neglectful of ModeledBehavior.com for a little bit while we fill in for Megan. Make sure to stop over, and you’ll learn you can cook a mini-pie in a jar.

The entire Modeled Behavior crew will be guest blogging at the Atlantic this week for Megan McArdle.

Come over and support us.

The relationship between the Amish and technology is not so absolutist as most probably imagine. A recent article on the use of Facebook among Amish teens illustrates the complex, varied, and surprising ways in which the so-called Plain People interact with technology:

There are no statistics to show how many Amish are on Facebook, the social networking site used by an estimated 500 million people worldwide. But some, in a community that shuns electricity in their homes, won’t buy cars and maintains traditional garb, say the number of Plain kids using Facebook — often logging on via their cellphones — appears to be increasing….

…Erik Wesner, an author who runs a blog called “Amish America,” said he corresponds with many Amish via email. Typically, he said, email is justified as a business concession…

…The Amish slowly, sometimes surreptitiously, adopt new technologies. A century ago, Amish bishops — who set the boundaries for what is and what isn’t permissible for their congregations — forbade phone ownership. Eventually, they permitted groups of Amish to install “community phones” in “phone shacks” outside homes. Then some of them allowed phones inside businesses….

One might speculate that increasing technology would erode Amish communities but unlike many other fundamentalist communities, the Amish seem to want children to have a real choice about whether they stay in the community, and to do so with their eyes wide open. This can be seen in the Amish tradition of rumspringa, which allows Amish youth to live life outside Amish rules and see what their lives would be like if they left the community. If full exposure to the temptations of the modern world were enough to lead to the decline of the Amish, then one would expect it to have happened already. As the article details, Amish children have always dabbled in new technologies:

Still, [one local] Amishman said, Amish youth have always been attracted to new technologies and trends. “When automobiles came out, some Amish rode in automobiles,” he said. “When Rollerblades became popular, some Amish Rollerbladed. Most anything that comes along, some Amish kids will pick it up.”

For now, the reaction to Facebook in Amish communities ranges from preaching against it directly to being completely unaware of it:

The Amishwoman at the stand near Gap said one local minister actually did preach against Facebook in recent weeks. Others, she said, are vaguely worried, aware that it’s happening but unsure how many are involved. And they’re also hampered by the fact that many older Amishmen and women simply don’t know what Facebook is.

Ezra Klein defends against Megan McArdle’s told-you-so on health care reform.

Yesterday, Megan McArdle linked to the study showing that Illinois children on Medicaid have trouble getting appointment with specialists and wrote “proponents of health care reform are gnashing their teeth, while opponents grimly say ‘I told you so.’” Really? Why?

The study gets at two problems: In an effort to control costs, Medicaid pays doctors too little, and too many uninsured people go without care. These are exactly the sort of problem health-care reform is designed to address. Most directly, the law dramatically expands coverage and increases Medicaid reimbursement rates, particularly for primary-care doctors. That doesn’t do much for the specialists, who were the subjects of this study, but it’s a start.

More importantly, the law is thick with efforts to control costs in the health-care system itself — and in Medicaid itself — which is the only approach that’s really sustainable over the long-term. They may or may not work, but people who believe they’re our best hope, at least for the moment, aren’t gnashing their teeth at this study. They’re saying, “See? This is what I’ve been trying to tell you about. This is why we had to pass that law.”

I remain skeptical that any of these essentially demand side policies are going to do the trick.

As Megan notes some hospitals are claiming that Medicaid reimbursements are running below their marginal costs. That is, they would do better to leave a bed empty than fill it with a Medicaid patient.

I find this maddening. Not for the usual moral implications sort of way. Just in the fact that I am faced with a business which cannot profitably perform this service at a reimbursement rates far, far, far above the median wage.

There is nothing that can be done? Really? Nothing?

I can’t put an out of work construction worker in that room with a thermometer and pay him 7.50 an hour to take that patient’s temperature. I cant hire a 16 year-old kid to haul around one of the blood pressure monitors, hook each patient up to it and then type the results into some old rusty laptop.

You have got to be kidding me. There is this much money on the table and there is just no profitable use you can put it to?

Are you running a business or a hole in the ground where profit goes to die?

I mean crap, can’t I at least hire someone with a iPhone to walk into each room and ask the patient a series a questions, record on the iPhone camera and the email the results to a triage nurse in India who can give me a heads up on what’s wrong with this patient.

We have lots of unemployed workers in America. We have lots of people who want some form of medical care. There is no way to get these two groups of people together. Just NO WAY?!

I hate to keep going with this but a fair number of my Medicaid patients might be old, illiterate or not have access to the internet. I can’t pay some kid to type in their symptoms into FirstConsult and at least find out something?

This is just a joke. I have workers. I have capital. I have customers. There should be some transactions going down here.

I don’t know how to see this as anything other than a serious supply side catastrophe.

Two comments on this, starting backwards. David Henderson building off of Ron Paul’s – admittedly mixed up – answer on manufacturing jobs.

The other candidates did a poor job too. All of them seemed to see the lack of manufacturing jobs as a problem per se.

As is my wont, allow me to get a little meta here. Suppose that the topic had not been manufacturing jobs but infanticide. If the candidates had taken it for granted that infanticide was a bad thing per se, would we have let them off the hook?

At the end of the day, infanticide happens and the more infants there are, all else being equal, the more will be murdered. The history of society is one of more babies being born and consequently more of them being murdered.

I have the strong urge to go deeper and suggest that the configuration of subatomic particles we call a dead baby is not in its essence more or less outrageous than the configuration of subatomic particles we call an unemployed manufacturing worker.

These configurations matter because they matter to someone. People are obviously very concerned about unemployed manufacturing workers and thus they matter, per se.

On a more concrete level we can see this by imagining that all of the former manufacturing workers had owned stock in their companies. The companies then discovered some way radically increase productivity, lower costs and send profits through the roof. All of the former workers lost their jobs but became millionaires. Would there be a lot of handwringing over this – I am guessing not.

Which is to say that people complain about things because they are painful, we should take their pain seriously and speak about what can be done to alleviate it.

If the answer, is: it is not worth it for me to alleviate your pain because any feasible method would be too costly to the whole economy, then we have to recognize that that is in fact our answer and does in fact suck for the person hearing it.

Now, on to Ron Paul, he said many things but key among them was

But as long as we run a program of deliberately weakening our currency, our jobs will go overseas, and that is what’s happened for a good many years, especially in the last decade.

This is, of course, exactly backwards. Weakening our currency will bring jobs to America. This is why exporting countries have a deliberate and successful policy of weakening their currency.

However, my point is not to hit Ron Paul over the head with this. I am sure he has sort of put this together in his head. Its to point out how ubiquitous the trap of imagining that good things lead to other good things can be.

Ron Paul believes for many reasons that a strong currency is good. He also believes that seeing all of these job losses is bad. My strong suspicion is that it is difficult for him to reconcile the idea that a good idea could have such a bad outcome.

However, of course this happens all the time, because happiness and prosperity are not rewards for doing the right thing. They are simply one of many possible states of the world that result from the unique interaction of the events which preceded it.

Very few choices are clean in the sense that they will make everything better and nothing worse and none are clean with probability one.

So lets step back from all of this and looking at the policy dimension of the jobs question. My narrative is that the United States has somewhat passively allowed itself to get into a position of being consumer of last resort.

Other nations, most recently China, have run deliberate policies to suppress household consumption. The result was a rapid increase in both investment and net exports. This has the inverse effect of increasing US consumption and decreasing US net exports.

The costs and benefits of this policy accrue unevenly to Americans. Most Americans benefit slightly in the form of cheaper consumption goods. A few Americans benefit immensely by working in the financial sector of a country experiencing huge capital inflows and cheap financing. Another subset of Americans suffers miserably from losing employment and seeing the agglomeration effects that built their entire communities unravel.

The true policy question is: are we indifferent to this? I don’t think a simple appeal to Laissez-Faire is enough, if for no other reason than because this is not a Laissez-Faire outcome. It is the result of the deliberate policy of another government. Should that matter? I am not sure.

At a minimum, however, I think as intellectuals we should recognize the suffering of people affected by this and address it directly. Even if what we have to say is: I’m sorry but there is just nothing I think we should do to help you.

I haven’t read her book yet but based on an interview with Daivd Leohardt I’d wager that Diane Coyle is the Amy Chua to my Bryan Caplan. A snippet:

There is too much cynicism about politicians, I think. Most people go into public life because they start out with the noble ambition making things a bit better for their fellow citizens. So why do they all seem to end up doing short-term pork-barrel politics?

I agree that most people go into politics to for noble reasons. However, at least is budgets are any guide, very little of what they do seems to be pork barrel projects. Moreover, many of those projects are the type of investments that Coyle seems to be supporting.

Here is sampling of some of the larger projects, taken directly from the 2009 report of Citizens Against Government Waste, a group not friendly to pork barreling.

- $4,545,000 for wood utilization research in 10 states by 19 senators and 10 representatives. This research has cost taxpayers $95.3 million since 1985. One would think that after 24 years of research all the purposes for one of the world’s most basic construction materials would have been discovered.

- $80,655,000 for 86 projects by Senate CJS Appropriations Subcommittee Ranking Member Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), including: $900,000 for fish management at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab; $800,000 for the University of South Alabama for oyster rehabilitation in Mobile; $500,000 for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for public education in Mobile; $500,000 for NOAA for the Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center in Mobile for education exhibits; $475,000 for the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville for missions systems recording, archival, and retrieval; $400,000 for the McWane Science Center in Birmingham for education and science literacy programs; and $100,000 under the COPS program for the Talladega County Commission to make radio upgrades.

- $41,065,000 for 26 projects by Senate CJS Appropriations Subcommittee Chairwoman Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.), including: $1,000,000 for the University of Maryland College Park for its Advanced Study Institute for Environmental Prediction to study climate impacts and adaptation in the Mid-Atlantic region; $1,000,000 for Coppin State University, Towson University, and the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute to partner on a program to increase the number and quality of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics teachers in the region’s public schools; $550,000 for the NOAA Chesapeake Bay office for blue crab research; $500,000 for the NOAA Chesapeake Bay office for a network of environmental observation platforms; and $500,000 to Charles County public schools for a digital classroom project

- $190,000,000 for 33 projects by Senate Defense Appropriations Subcommittee Chairman Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii), including: $23,000,000 for the Hawaii Federal Healthcare Network, $9,900,000 for the U.S.S. Missouri (which costs $16 for an adult to tour and receives 100,000 annual visitors), and $3,600,000 for intelligent decision exploration. That is something many members of Congress should be doing.

- $87,025,702 for 28 projects by then-Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee Ranking Member Pete Domenici (R-N.M.), including: $18,000,000 for middle Rio Grande restoration; $4,757,500 for climate change modeling capability; $3,828,000 for New Mexico environmental infrastructure; $1,914,000 for Army Corps of Engineers construction of the Acequias irrigation system; $1,903,000 for the La Samilla Solar Through Storage Project; $1,903,000 for the Center of Excellence and Hazardous Materials; and $200,000 for the middle Rio Grande endangered species collaborative program.

- $73,690,000 for 35 projects by Senate Interior Appropriations Subcommittee Chairwoman Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), including: $5,600,000 for two projects at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area; $5,000,000 for San Francisco Bay restoration grants; $1,250,000 for the Angel Island Immigration Station; $800,000 for a tunnel at Yosemite National Park; and $460,000 for the Whiskeytown National Recreation Area. In November 2008, Whiskeytown participated in the National Park Service’s Artists-in-Residence Program. Participants include sculptors, painters, land-artists, and video artists, who get to spend up to four weeks in an “artist’s cabin … to produce new works.”

That, however, isn’t even our main point of disagreement. I think the main problem with being far sighted about the future is that no one knows for sure what the future is going to be. That makes future public policy especially hard and it planning for the future especially dangerous.

What I would point towards is contingency plans, guides of the nature: When You are Engulfed in a Credit Crisis or When A Giant Tsunami Has Struck, rather than trying to chart any particular course.

David Leonhardt makes the case for targeted payroll tax cuts

In my column Wednesday morning, I argued for a similar approach for a new payroll-tax cut for businesses. Rather than giving a tax cut to all businesses, as the White House seems to be mulling (though the details are unclear), a targeted tax cut would reward only those business that added to their payroll. This approach does less to increase the deficit and yet could do more to promote hiring.

I have to take a fairly strong stand against this type of thinking. While targeting sounds very savvy I think in practice it’s a bad idea. One its just hard to pull off neatly. We are driving a freight train here not a Maserati. No dicing through the orange cones.

Moreover, the point of the stimulus isn’t simply to pull hiring forward, though that’s not a bad outcome. It is to lesson the constraints on business and to get cash flowing in the economy.

Right now the government can borrow money at less than the rate of inflation. That means free in real terms. It can give that money to business who may or may not be cash strapped. If they are then this opens up new opportunities for them in a dramatic way.

If the businesses are not cash strapped then in the absolute worse case they simply hoard the cash and its no harm, no foul. Remember we are paying less than the rate of inflation to borrow. Perhaps, however, they will find a useful investment for it, which means the total return in the economy goes up.

The government borrows money for free, gives it to businesses who then invest it with some positive rate of return. That’s good.

Lastly, it also lowers the cost of labor. That’s good because it mimics painful wage declines that would be needed to clear the labor market. Rather than waiting for slow moving inflation to drive down real wage rates, we can drive them down right now with a business side payroll tax cut.

From the BLS

The index for all items less food and energy rose 0.3 percent in May after increasing 0.1 percent in March and 0.2 percent in April. The shelter index rose 0.2 percent in May after increasing 0.1 percent in each of the seven previous months. Both rent and owners’ equivalent rent rose 0.1 percent; the acceleration in shelter was due to the index for lodging away from home, which rose 2.9 percent in May after being unchanged in April.

Increases in the shelter component looked baked into the pipeline to me. Hotels occupancy is rising. The number of living units has not kept pace with population. The number of residential starts is at record lows. Inflation in shelter is coming.

Now I think we should be returning to trend in prices so this doesn’t bother me, but I don’t want everyone to be freaked when core inflation rises over the next 12 months like it was some out of the blue, everything has changed phenomenon. We are not building enough housing and that is going to drive up rents.

Via Ezra Klein

Perhaps the most consequential argument happening in the Republican Party right now is whether a “tax increase” isanything that increases total government revenues, even if those revenues come from closing tax breaks, or whether it means raising marginal tax rates. If the former, there’s a deal to be struck on the deficit that pairs spending cuts with new revenues that come from cutting tax breaks and closing loopholes. If not, well, not. Grover Norquist has been leading the charge against this kind of deal. He says that closing loopholes and ending breaks is only acceptable if the new revenues are immediately plowed into further tax cuts. And today, in an important test vote, he lost. Big

One of the things I’ve noticed is that is gets very difficult to even have a normative opinion on these matters once you start thinking about them in a positive way. It seems almost inevitable to me that tax revenues in the United States will rise substantially over the medium term and so caring about it one way or the other seems pointless.

Its like caring about whether the sun will rise.

There are details to be worked out of course but the basic outline is there. I am betting on VAT, but think the GOP would do better to argue for expanding the payroll tax. Slight chance for a millionaire’s tax bracket and other soak the rich measures but I am doubtful at this point.

Catherine Rampell is exploring a thesis about the hiring practices. A sample

On Friday, I wrote about how equipment and software prices are getting rapidly cheaper while the cost of labor has been getting more expensive, making capital a more attractive investment to companies than people. Tax incentives that encourage earlier capital investment may be helping, too.

Importantly this only makes sense if capital and labor are substitutes in production. Typically we think of them as complements.

Lets take some obvious examples. Suppose to create welded metal I need both a welder and welding torch. The welding torch goes down in price. That means that its actually cheaper to create each piece of welded metal. This will allow me as a factory owner to either lower my price, sell more welded metal while maintaining my profit margin.

However, to do this I will need more welders. So a fall in the price of welding torches, increases the demand for welders.

On the other hand suppose that I am an airline considering whether to have more booking agents or whether to invest in more sophisticated booking software. Specialized software can run well into the multi-millions but if it gets just cheap enough it might actually be a better deal than new agents.

So the falling price of capital alone isn’t enough. It depends on how the capital interacts with the workers. Moreover, it would take some fancy math to show this, but until capital can do everything labor can do – that is until the singularity – some types of jobs must be compliments to capital.

Those jobs will always be in more demand as capital get cheaper. The question is how much skill you need to do those jobs. This is the whole issue of skill-biased technological change.

Perhaps the key point differentiating the PSST view from a more traditional AD-AS view is assumptions about the speed at which new market connection are made and factors relating to the co-variance in that speed.

If connects were instantaneous then we could just retreat to Walrasian Equilibrium and be done.

If connects are not instantaneous then first we have curious question about co-variance. Why are so many connects broken or made at the same time. Further, why is it that sometimes it seems rapid change is making connections faster than breaking it and other times its going the other way.

A simple appeal to well, sometime things are like this, sometime they are like that, will not do. The network is massive. Connections happens every day. When we look at employment data we are looking at the mean number of connections over some period of time. The central limit theorem should apply.

That is overwhelmingly things should just move along as if we were in a smoothly rotating economy. Not because we are, but simply because the number of changes is so massive and so spread out randomly.

We have to appeal to major systemic shocks in one form or another to get around this. Or, perhaps some sort of collective reallocation of attention, though I am not sure how far you can go with that.

Yet, this brings up the role of policy and liquidity. Suppose that credit “greases the wheels” of connection generation. Its not hard to imagine how. Capital is easier to finance, start-up costs easier to obtain, bumps in the road easier to smooth out.

Now are we moving to a synthesis where increased connection generation is the transmission mechanism for monetary policy?

More explorations in stagnation

Suppose I am run a shop that builds engines and I figure out a better technique for inspecting my engines. I employ it and productivity goes up. My competitors hire away one of my engineers, find out the technique and also employ it. Pretty soon every engine manufacturer is using it and the world gets better engines. That learning by doing, knowledge spillovers and TFP all rolled into one. Its classic growth.

Now flash forward. Engines are being inspected by machine. I figure out a better program to inspect engines, I copyright it, sell it. That’s investment in equipment and software, profits for me as tech entrepreneur and capital deepening. Not so classic growth.

Well here is a chart of real GDP versus real investment in equipment and software.

Growth in investment in equipment and software is well outpacing GDP. At this point its still a pretty small fraction about 7.5%, however, we all know what happens when a portion of GDP grows faster than GDP, it eventually becomes GDP.

Here is the same thing in natural logs to give a better sense of the growth rates.

and once more on the same axis to show the gap closing

Since no one else that I know of has said this, I will make my comment let the objections come in and then address them. I am by no means suggesting that this analogy is iron clad.

Lots of people think that if the government spends money hiring folks this will only crowd out other spending from the private sector and do nothing to bring down unemployment.

I would ask them: do you also believe that is true of Apple or Google or any other private firm?

If not, then why are they different? Lets discuss.

Well obviously Google and Apple are private firms. Government and private firms are not the same. However, that’s not enough.

Cardinals are not Robins, but they both lay eggs, fly and engage in other bird-like activities. Which is to say that we have to be explicit about how these two things are different and why that difference matters.

One guess might be the difference is that government must tax or borrow and this uses up real resources. Yet, in terms of resource tracking private firms are are also subject to an adding up constraint. This is different from value-add which I will get to.

The money to pay the workers has to come from somewhere. The money to buy the capital has to come from somewhere. Even if it comes out of Apple’s cash hoard that represents a decline in loanable funds. Ironically, much of it represents a decline in the demand for T-bills, which is basically the dual of the increase in the supply of T-bills that happens when the government borrows.

Why isn’t it the case that Apple or Google employing resources simply reduces the amount available to others. And if so, why do we think that would bring down the unemployment rate?

As a short way out I would suggest that at full employment we don’t believe that Apple or Google spending money would bring down the unemployment rate. We think they would, indeed, take away resources from other uses and we believe that in doing so they would bid up the price of those resources. That’s part of why we think full employment and wage increases go together.

What I think we believe – and this gets to the Cardinal/Robin thing – is that Google or Apple would only be able to do this if they were moving resources to better uses. That is, yes they are crowding out other types of economic activity but they are doing so in favor of a superior activities, types of activity that produce goods of greater social value.

Because the government faces no market test there is no assurance that when the government pulls resources out of society that it is doing it for purposes with greater social value. It could be doing it for “pork projects” or more generally it could just be making an honest mistake. Policy makers really thought the universal combobulator was a good idea but they were wrong and since there is no market test, we will never know.

However, when we are away from full employment then it either seems that more spending on the part of private firms could not reduce unemployment or more spending by government could.

In a bit of shameless self promotion I want to point out just how right I have been. Any bias on my part in reporting or analysis should just be brushed under the rug.

Issue One: Monetary Policy

I made a call sometime ago for a higher inflation target in order to being about negative real interest rates. The Fed turned down that in favor of QE2, a policy that was inferior but still good. We saw interest rates go negative for a time and that was associated with increased asset values and a speed up in consumer spending.

Yes growth hasn’t been as high as we would like but I can’t help it if the government keeps firing people.

Issue Two: Near Term Growth

In the last two months people have been getting sour on US growth because of some bad reports. I remained sanguine about the whole thing.

Now here are Dudley and Bernanke respectively

In part, this softness is related to factors that I expect will prove transitory. These factors include the rapid rise in gas and food prices that I noted earlier, supply disruptions associated with the earthquake in Japan, and severe weather and flooding in parts of the United States. All three suggest that the soft patch may not persist.

and

. . . with the effects of the Japanese disaster on manufacturing output likely to dissipate in coming months, and with some moderation in gasoline prices in prospect, growth seems likely to pick up somewhat in the second half of the year. Overall, the economic recovery appears to be continuing at a moderate pace, albeit at a rate that is both uneven across sectors and frustratingly slow from the perspective of millions of unemployed and underemployed workers.

Issue Three: Payroll Tax Cuts

I called for large Payroll Tax cuts early on as politically palatable and economically sensible. We finally got a small one in late last year and now may be poised for another.

President Barack Obama’s advisers have discussed seeking a temporary cut in the payroll taxes businesses pay on wages as they debate ways to spur hiring amid signs that the recovery is slowing, according to people familiar with the matter.

Issue Four: Medical Screening

I have persistently questioned the usefulness of medical screening and preventive measures. Now it looks like we’ve been taking women’s ovaries for no good reason.

Calling into question the effectiveness of current ovarian cancer screening techniques, the researchers also found that more of the women screened annually had surgery to remove their ovaries and suffered complications related to false-positive test results — meaning a screening test suggested they had ovarian cancer when they really didn’t.

The finding is in line with other recent research that suggests annual screening doesn’t prevent deaths from the disease, which kills most women within 5 years of their diagnosis (see Reuters story of May 18, 2011.)

Issue Five: Taxes vs. Transfer Payments

I’ve said that its transfer payments not taxes that cause people to work less. Recently the NYT economics team has been on a tear about disability payments and labor supply. A sample

In the worst economic times of the 1950s and ’60s, about 9 percent of men in the prime of their working lives (25 to 54 years old) were not working. At the depth of the severe recession in the early 1980s, about 15 percent of prime-age men were not working. Today, more than 18 percent of such men aren’t working.

…

For growing numbers of these men, the federal disability program is a significant source of support.

…

Perhaps the worst thing about the disability program is that, once in it, many people never leave. They were eligible for disability because of a legitimate injury. But once they stop working, many become less appealing job candidates and less motivated to find work. Their chances of finding well-paying work shrivel. Relative to a low-paying job, especially if the job exacerbates a chronic injury or chronic pain, the modest monthly disability payment of about $1,100 on average can look appealing.

Issue Six: Housing Shortage

I have argued that there is coming housing shortage in the US and that the bubble in home construction wasn’t nearly that big. People countered with vacancy rate and homeownership stats that were at record levels. Now those stats are being questioned

Here is housing economists Tom Lawler

My frustration with the conflicting data on US housing that comes from different reports from the Census Bureau, and the inability of Census analysts to explain the differences or even tell “private” analysts what time-series data they should use to analyze US housing trends, has existed for at least a decade. Occasionally that long-standing “frustration” has led me to write that it almost appears as if Census officials and analysts “don’t care” about the conflicting data.

When schools are faced with a budget crunch, as so many are, art teachers and art classes are among the first to go on the chopping block. As the New York Times reports, this appears to be the case in New York City:

For the first time in four years, the number of certified arts teachers in the city’s public schools is declining, according to a report to be released by the Center for Arts Education on Thursday.

In 2009-2010, there were 135 fewer arts teachers in the city schools than in the previous school year, after principals chose to cut positions from their budgets or not replace arts teachers who left. The 5 percent drop puts the number of certified arts teachers working in the schools back to where it was in 2007, when the city first began to survey principals….

…Schools, however, have also cut back greatly on other spending for the arts. Since 2007, when the city began surveying schools’ art education, spending on supplies has dropped to slightly more than $2 million from over $10 million. In a system with more than a million students, that comes to about $2 per student.

This general scenario matches up with other stories I’ve seen. But why should art be on the chopping block before history class? I believe we romanticize history, making it seem practically and ideally more important than it is. People defend history in the gauzy language of citizenship, with appeals that rarely rise above aphorism. “Those who don’t history are bound to repeat it”. This doesn’t hold up in a practical sense though. There’s a reason the phrase isn’t “those who have history as a significant part of their high school curriculum are bound to repeat it”. Being taught history doesn’t make you better voters unless you remember that history. I’m not going to go down the litany of things that huge percentage of Americans incorrectly believe about history, instead I’ll just give one prominent example. How many hundreds of millions of dollars to we spend each year teaching kids about the Civil War, and still 42% of people don’t know we fought it over slavery?

If we want students to know the most important facts and stories about history for the sake of those facts, then having them watch a few documentaries should cover the bases pretty well. As Will Wilkinson pointed out to me, history is something anyone with reading comprehension can teach themselves, in contrast art is a skill that in most cases requires careful instruction. Like I said, even people without reading comprehension can learn most of what they do in high school through documentaries and the History Channel.

Ideally speaking, I don’t think history is the most important subject when it comes to making better voters. You’d do better off to drill students on economics 101 and the basics of the budget. Maybe then we’d wouldn’t have a citizenry convinced that foreign aid is a large portion of our spending, and that understands the downsides of price controls. More importantly schools could stop reinforcing the notion that voting is some moral obligation, and let people know that voting on the basis of uninformed biases is far worse than not voting whatsoever.

There’s also a large cognitive dissonance whereby we view art as being something soft, idealistic, unpractical, and unserious compared to other school subjects. Art is a fun distraction, whereas history is serious business. But of the two art is clearly the more practical real world subject. Many serious, button downed, grown-up careers require artistic skills: architects, marketing, graphic design, engineers, web designers, city planners… the list goes on. Which careers require knowledge of history? Journalists, history teachers, politicians? It seems as though the caricatures of these fields should be exactly the opposite, and that history should be viewed as soft, idealistic, and unpractical, whereas art should be viewed as the hard-nosed practical subject of serious people.

Even in these cases where a career requires knowledge of history, like those above, what they need is 60% confined to modern world history, and the other 40% to modern world history. Where does knowledge of explorers, Mayans, and pilgrims come into play in any career? In art class even when you’re learning how to do stuff you won’t directly use in the future, you’re picking up artistic skills that have wider importance than their immediate application.

For the modern economy, for the betterment of our country, I say down with history, up with art.

Freddie DeBoer has a recent post on education that I think is demonstrative of a fairly common way of thinking about our educational system:

You won’t find this in most education reform debates, but the fact is that a huge part of our education problems are found among a relatively small subset of our public school populations. Many millions of students pass through American public education and are perfectly well served, ready to go compete in that global marketplace I keep reading about. And then you have a numerically small minority who are terribly underserved, in terms of educational outcomes, and who drag down our educational statistics considerably.

My question is whether he would judge how well the American economy is doing using similar logic? I believe Freddie had his druthers we’d undertake some fairly radical changes in our economy, including a much different redistribution system. If the performance of our education system does not merit radical change, then does our economy? I’m not sure the former is obviously outperforming the latter, especially if you judge them by all but the bottom of the distribution.

First, consider that the main long-run criticisms of our economy are related to growth, not levels. In levels we are still the richest country in the world, which is why people complain about stagnating worker incomes, not low worker incomes. But our education system is failing when measured by both level and growth. In comparison to income, which is unbounded in the long-run, there are obviously limits to growth in test scores, but we are far from topping out on these measures. As Tyler Cowen argues in The Great Stagnation, we probably should expect test scores to be going up every year:

Keep in mind that according to the so-called “Flynn effect,” each generation has higher average IQ scores than the last. So if we’re getting smarter on relatively abstract IQ tests but not getting better test scores at school, possibly schools are declining in their productivity, despite all the extra money spent. Or take the constant scores in mathematics. We are a wealthier and smarter nation, more reliant on mathematics in our technology, and there is more mathematics “on tap” in any home computer. If anything, instructional progress, and thus progress measured in scores, is to be expected. You might also think that mathematics hasn’t changed so much in decades, so the better teaching techniques should spread and push out the lesser teaching techniques. That does not seem to have happened on a national scale, and again we must consider the possibility that our educational productivity has on the whole declined.

Median wages may have stagnated since the 70s, but the graduation rate has declined since the 60s. Output in both is a function if inputs as well as productivity, but that’s true in both cases.

The education system and the economy are apples and oranges, and so I’m not looking for the definitive answer as to which is performing better; that may be an impossible question. On the one hand, the education system may be more dependent on inputs that are exogenous to it. On the other hand, in the long-run a lot of inputs like poverty are not completely exogenous to the education system. Furthermore, the education system is a majority public run, which makes how it functions more “manageable”, so to speak, than the economy. But this apples to oranges exercise what I want to do here. I just want to question whether a similar level of apologetics that Freddie applies to the education system leads one to conclusions about the economy that are quite moderate, and even conservative. To say that a system does not need a lot of change because it serves everyone but the worst of well is not a very progressive way to view the world.

From Pew

I keep telling my friends on the right: you really want to raise the cap on SS contributions.

You are talking about the moving to a system where the dominant source of revenue for the Federal Government is a flat, deductions and exemptions free tax on labor.

No other course of action makes holding down capital gains taxes more likely. No other course of action a millionaires tax bracket less likely. No other course of action has less tax avoidance and evasion associated with it.

Medicare will not be killed. This is your shot. Take it.

To my mind there are few things that tax intellectual ethics more profoundly than whether the psychotropic debate should be had in public. It is my general feeling that it should not.

My blog is not read by the general public but I will make no attempt to be transparent. Those in the know, know what I am talking about.

The important thing is this: to my knowledge no one disputes that effects exist. They dispute the source of the effects. If some folks are asserting that harm is being caused this is important and we should talk about it.

However, we should talk knowing that we are playing with fire, that discretion is needed and that the public space may not be the place for this discussion. Happiness matters and it matters a lot. Suffering matters and it matters a lot.

I understand the escalation and cocktail problem and I think it is more reasonable to address them directly. However, to address some of my intellectual counterparts I will say this: if we don’t have a model of infection then practically speaking, pain is caused by a lack of aspirin.

Pain is bad.

So perhaps this constitutes a predictive difference between myself and Arnold Kling’s PSST school. I want to reiterate that while my best guess at this point is that PSST is not an important way to think about modern business cycles, my guess is that it is important both in growth and labor market dynamics.

Anyway, it seems that Pawlenty and maybe Obama have said that the US can achieve 5% growth. Sorry I am not up on details, this is a busy summer.

Its my understanding that this claim has been ridiculed by numerous folks.

I, however, will predict that the US will achieve an average 5% real growth over a sustained period say 12 quarters more starting with in five years. So I guess that’s like saying “within the next 8 years”

Perhaps, Arnold and I can make this into a bet.

While this doesn’t directly conflict with PSST and isn’t guaranteed under and AS-AD paradigm, it should be more likely if they’re really is such a thing as an Output Gap. Thus there should be some bet that both of us would find fair.

Now to be clear I don’t think that Obama or Pawlenty or Romney will have anything to do with this. Maybe the Fed will. More likely, at this point, is that the downturn will snapback on its own once household balance sheets are repaired. As long as the government doesn’t actively seek to stop this I think there is a reasonable chance this will occur within 5 years or so.

Now there are lots of reasons why this prediction could be wrong but AS-AD could be right. However, the good thing about a bet is that as long as its more likely to be right under my view of the world there is some wager that both me and someone who disagrees with me should be willing to accept.

Edit: unnecessary crankiness removed

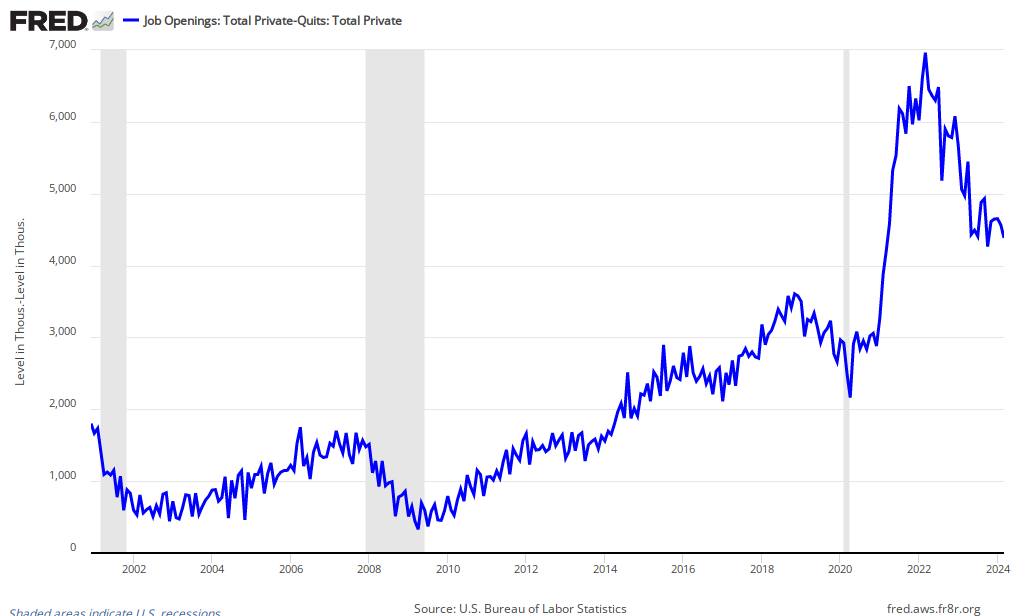

Here are private sector job openings minus private sector quits, a stat I am for the time being referring to as new private labor demand. The idea is that an employer might be offer a new job because she wants to expand the workforce of because she lost a worker.

I want to pick up the expanding the workforce component.

Kevin Warsh, an exiting Fed governor, has a recent interview in The International Economy in which I want to highlight his views on the anemic recovery:

TIE: The current recovery has produced less than half the growth rates achieved during the recovery after the 1981–82 recession. For example, for most of 1983, growth stayed consistently above 8 percent and for a time exceeded 9 percent. Why do you think the current recovery has been so modest? Some would argue it’s a Ricardo equivalence effect—the size of the public and private debt is inhibiting consumption. Others say the stimulus wasn’t large enough. Others argue there’s never been a major recovery without housing leading the way, yet housing is still in the basement. If you bought a house within two or three years of the peak, for example, negative equity makes it difficult to refinance even if interest rates are low. Banks still have a lot of inventory on their balance sheets, particularly with the level of foreclosures. Maybe banks don’t want to write off bad assets until there are profits. Would removing inventory from balance sheets and putting it back in the market help clear this process and make housing more affordable—and thereby improve the prospects for a healthier recovery? Why has this recovery been so modest? Is the answer simply that recovery after financial crises is always difficult?

Warsh: Only by the standard of the deepest, darkest day of the crisis is this economic recovery even plausibly satisfactory. On a historical basis, the economic recovery is modest, and unacceptably so. Some describe this recovery as the “new normal” and suggest we should just get used to it. Others suggest that recoveries from global financial crises are inevitably weak, and so we should lower our standards. I call this the new malaise. Instead of lowering our standards, we should improve our policies and raise our expectations.

So why is the recovery weak? First, the symptoms have been confused with the disease. Some policymakers have tried to steer a housing recovery without an economic recovery. So there have been a dozen or so programs to “fix” the housing crisis on the theory that once that’s repaired, the broader economy will come roaring back. These housing programs, however wellintended, have done little, in my view, to help the housing markets or the real economy. A housing recovery will begin when real household incomes improve, not before.

Second, intentions aside, the broad suite of macroeconomic policies has tended to favor the big over the small—big banks have been advantaged over small banks; big businesses have been favored versus small businesses; and those big multinationals with access to the global economy and global financial markets have benefitted more than those on the front lines of job creation.

Third, macroeconomic policies, in my view, have been preoccupied with the here and now, not the long term. So going back several years, Washington has compensated for a faltering economy with temporary programs that plug quarterly GDP arithmetic, but do far less to support longrun growth. Massive stimulus has proven not to be as efficacious as many academic models would suggest.

I, personally, have never bought into the notion that financial crises produce slow recoveries. The problem is confusing near-zero interest rates with “easy money”. It isn’t the financial crisis that causes anemic recovery, it is inadequate monetary accommodation. This holds unless you happen to believe in infinitely elastic money demand over a significant period of time; which I doubt even Keynes actually believed, and in any case, has never existed in the real world. The Great Contraction of the 1929-32 caused an extreme financial crisis, however monetary devaluation of 1932-33 caused the highest rate of growth in industrial production in the history of the US, even with a severely damaged banking system. Warsh is correct that we shouldn’t be complacent, we should improve our policies, and raise our expectations…more importantly, doing so should be mechanical. Elsewhere in the article Warsh says that we need to focus on the trajectory of inflation, and not where inflation has been. I think he should be even more creative, and call for a NGDP level target. Not only would this be a policy improvement, but given a credible central bank promise to a target path for NGDP (with a commitment to compensate for slack or overshoots) expectations of future Fed policy would become more or less automatic. This is what we should strive for.

To me, there is no mystery as to why we are experiencing an anemic recovery.1 In the deepest, darkest days of the crisis, there was literally no focus on monetary policy. Indeed, people were idly claiming that the Fed was being accommodative, even as it held the Fed Funds Rate well above zero while the TIPS spread collapsed, real rates soared, and various markets were in free-fall. There may, indeed, be a new normal, in which instead of raising nominal wages and prices (the easy way out), we grind through dis-inflation/deflation in order to bring real wages and prices into line with the new output trajectory (the hard way out)…but everyone needs to realize that is not a cruel fate, it is a choice.

Matt Yglesias ridicules Grover Norquist

According to the Norquistian theology, a good small-government conservative can’t agree to close a tax loophole that’s bad public policy in order to entice Democrats into agreeing to spending cuts. You can’t achieve efficiency enhancing reforms to the tax code by using the prospect of enhanced revenue as a sweetener, and you can’t broaden the coalition for spending cuts by using enhanced revenue as a sweetener. So the tax code stays inefficient and the spending level stays high, all so the members of the True Faith can be unsullied in the purity of their complaints about the inefficiency of the tax code and the high level of spending.

I think Grover’s plan makes more sense than Matt is giving him credit for. The idea is not to reform the government, its to bankrupt it. Once that is done spending reductions will come mechanically.