You are currently browsing the monthly archive for February 2011.

There was no shortage of comments on my last post, but there is one that I can clear the air about quickly.

Jeff comments

You write, “Does industry likewise have a right to create and have enforced by the state contracts which restrict supply and raise prices.” Are you honestly unaware that this happens? Have you never heard of the sugar tariffs that the federal government has had in place for decades? Do you believe they exist because of teachers’ unions in Wisconsin? Are you really unfamiliar with the pipeline between business organizations and lobbies and the legislation that gets passed in Washington and state capitals across the country? Maybe you guys are, since you and Adam complain about unions and such all the time (more Adam than you, in fairness), and yet I have no recollection of a posting decrying the negative, distorting influence of the Chamber of commerce.

My apologies for giving the impression that I was ok with agricultural restrictions. Opposition to these are practically de rigor among economics bloggers and I may not have done enough to make my position clear.

Agricultural tariffs are a disgrace, not only because they distort the market and raise prices on lower income Americans, but also because it makes it harder for Third World farmers to sell their crops abroad.

Though to be fair, this is what the Chamber said on sugar tariffs

The existing U.S. sugar program already represents a chronically flawed policy that creates and maintains an artificial gap between U.S. and world sugar prices. And now, rather than seizing the opportunity to fix this policy, Congress is poised to pass a Farm Bill that makes it much worse.

Both the House and Senate versions of the proposed Farm Bill increase, rather than reduce, price supports. And worse, the bill continues sugar marketing allotments, ostensibly to balance supplies, while simultaneously guaranteeing U.S. sugar growers an 85% share of the domestic sugar market.

Nonetheless there are points where the Chamber and I are sharply at odds. Their continued support for employer provided health insurance and the continuance of the health insurance tax exemption are among them.

It was clear from the beginning that the public sector union battle was going to expose fault lines between Pragmatic Libertarians and Progressives. For a time, a strain of self styled liberaltarians had managed to convince themselves that the American left was just a bit misguided and if they only understood the economic arguments against their favored policies they would reject them.

True, progressive allegiance to the nanny-state was strong but even here pragmatic libertarians felt the weight of the empirical evidence was on their side. When the progressive assault on salt, soda and even meat failed to achieve its goals progressives would abandon it; just as they abandoned the similarly widespread but similarly misguided notion that the state should own and operate the major industrial concerns.

In the wake of Wisconsin, Kevin Drum called a resounding but by no means solitary, bullshit, on those hopes and dreams

If unions had remained strong and Democrats had continued to vigorously press for more equitable economic policies, middle-class wages over the past three decades likely would have grown at about the same rate as the overall economy—just as they had in the postwar era. But they didn’t, and that meant that every year, the money that would have gone to middle-class wage increases instead went somewhere else.

. . .

If the left ever wants to regain the vigor that powered earlier eras of liberal reform, it needs to rebuild the infrastructure of economic populism that we’ve ignored for too long

This sentiment is resolute among progressive bloggers. The decline of economic populism in general and unionism in particular is the front line of the new war. Wisconsin its cause celebre.

This fault line strains a potential liberal-libertarian fusionism to its core. The health care debate could be dismissed as a battle between monopolistic health insurance companies and a monopolistic state for control of fundamentally dysfunctional industry. That the federal government might choke the health care serpent to death in its future efforts to balance its budget could be seen as consolation for the growth in state control.

However, there is no such consolation to be offered in the unionization battle. Economic populism is precisely what libertarians hope to dissuade liberals of and to the extent public sector unions matter at all, its because they stand in the way of educational reform. Making public unions the heroes of a new populist revolution is not going to make any of this any easier.

What I didn’t expect though was a divide even within the libertarian camp. Libertarians are coming out in favor of private sector unions. Will Wilkinson is a representative

The right of workers to band together to improve their bargaining position relative to employers is a straightforward implication of freedom of association, and the sort of voluntary association that results is the beating heart of the classical liberal vision of civil society. I unreservedly endorse what I’ll call the "unionism of free association".

That free association is to be respected is without question. What is at issue of course, are contracts in restraint of trade – that is, “the right to band together to improve their bargaining position”

Does industry likewise have a right to create and have enforced by the state contracts which restrict supply and raise prices. May the Airlines, invoking their right to associate, form an organization and contract to hike fairs? May the automakers enter into an agreement to sell their cars at higher prices?

In a perhaps more parallel example, may the pharmaceutical companies enter into a collective bargaining agreement with the health insurers that the health insurers will cover only non-generics or they will not be sold any patented drugs at all?

What justification can there be for permitting labor to enter into such contracts but not business? I can’t help but suspect that it is a sympathy for economic populism and the notion that what is bad for the business must be good for the worker.

We must not forget that these restrictions work by driving up the cost of hiring the least advantaged members of our society. A man who could be profitably employed before a collective bargaining agreement may be forced into a lower paying occupation or even out of the labor force entirely after collective bargaining.

Perhaps, Will can clear it up for me but it seems that this line of reasoning goes against the core liberal-libertarian message as articulated by Will himself

It’s best to just maximize growth rates, pre-tax distribution be damned, and then fund wicked-good social insurance with huge revenues from an optimal tax scheme.

From a YouGov analysis of partisan trends

Independents, interestingly, look more like Republicans on the use of guns, but more like Democrats on power tools, marriage and religion.

Another interesting bit.

[Partisan] differences exist despite the similarity of the content and programming on [TV] shows. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist (or a political scientist for that matter) to see the one obvious pattern here: the geographic location of the show seems to correspond to the partisan sorting. Democrats like the shows that take place in Miami and California; Republicans like the shows that take place in Virginia. I wouldn’t stake my Ph.D. on it, but it isn’t a pattern I would have expected a priori.

In the debate over public sector unions a lot of liberals have been arguing that they are a positive political counterweight to corporate interests and a defender of the working man, and without them democracy will fail, the American Dream will die, and the earth will drift into the sun… or something like that. I recently provided an example via twitter that I thought demonstrated this isn’t always the case: teacher union opposition to charter school caps, which you’d hardly call good for working class people.

Kevin Drum responded that a single incidence of union political malfeasance doesn’t make them bad overall. Well that would indeed be a silly argument to make, and were this the only example of unions being on the wrong side of educational reform then that clearly would be the argument I was making. But do I really have to run down the litany of bad policies unions have fought to keep, and good policies they’ve fought against in education reform? A clear indicator of how bad they’ve been is that the most anyone will say in their defense on education reform is that “well, some unions are embracing reform now in some places!”. That’s some defense. As Megan McArdle sarcastically pointed out on twitter “to be fair, it DID only take thirty years”.

But is education reform the only place the public sector unions have been a very important obstacle to good policy? Here’s another important example from Ezra Klein from way back in the health care debate:

I have bad dreams. Nightmares, really. They used to be pretty rare. Every fortnight, maybe. But ever since the public employee unionAmerican Federation of State, County and Municipal Employeestook a knife to Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), they’ve been coming more frequently.

Wyden, after all, is a liberal Democrat. AFSCME is a left-leaning union. Both are desperate for health reform. But AFSCME is spending its time attacking Wyden. Why? Because Wyden wants to replace the employer tax exclusion (I told you that thing was important!) with a progressive tax deduction that all Americans, not just those with good employer benefits, would get. That means the poorest among us would get slightly more and AFSCME’s members might get slightly less….

They’re hitting Wyden to demonstrate their willingness to attack anyone who touches their tax benefit. This is less an assault on Wyden than a warning to Wyden’s colleagues.

And AFSCME isn’t necessarily alone. The Health Care for America Now coalition, which includes AFSCME and other unions, has come out against touching the employer tax exclusion…

And all this elides a simple fact: Capping the employer health care exclusion is good policy. Eliminating it entirely would be better policy.

Of course, critics will say “Ok, you’ve got two policies charter school caps and the employer tax exclusion for health care.” But education reform is a big one, and obviously about more than charter schools caps, and as I’m sure Ezra would agree, getting rid of the employer deduction would be a really big step in reforming health care. But really, my opposition to unions can stand on economics alone: they’re an anti-competitive cartel, and like other cartels are economically undesirable. It’s union defenders who need to appeal to the political power of unions to explain their desirability. I’m just pointing out some pretty terrible examples where this isn’t the case. See Megan for more.

Here is the abstract from a 2004 paper that I missed but am reading now. Emphasis, of course, mine

A so-called “asset market meltdown hypothesis” predicts that baby boomers’ large savings will drive asset market booms that will eventually collapse because of the boomers’ large retirement dissavings. As good news to baby boomers, our analysis shows that this meltdown hypothesis is fundamentally flawed; and baby-boom-driven asset market booms may not necessarily collapse. However, bad news is that, in the case where meltdowns are about to happen, forward-looking baby boomers’ attempts to escape them will be futile and may lead the economy into a “liquidity trap”.

Allison Schrager writes

. . . people must rethink the social contract between state workers and taxpayers. As health care gets more expensive and people live longer, the old model simply isn’t sustainable. This means that either benefits must be cut (which, given legal hurdles, is unlikely) or state residents must pay more taxes.

An issue I have with the popular discussion of public sector pay and unionization is that on all sides there is a temptation to frame this as a moral question. What are worker’s rights? What are tax payer’s rights. What is the social contract and is one group cheating the other.

Some of this is unavoidable since public sector pay is influenced by the democratic process. Still we should not encourage it.

The public sector isn’t a stage on which to air our perceptions of the just society, either from the point of view of workers or tax payers. The public sector is a labor market.

In a labor market the greater the total value of the compensation offered the greater the size of the applicant pool. The question facing policy makers is at its heart, do we have too many applicants or not enough? Are our best applicants over qualified or under qualified?

If they are over qualified then you are paying too much. This is bad, but not primarily because it raises costs for tax payers. Obviously tax payers would prefer to pay less, but so would any customer for any service.

If the tax payer is buying a higher quality service than he or she needs then the problem is that we are wasting human talent. That public sector worker could be employed somewhere else in the economy and produce more value there.

On the other hand if public sector workers are under qualified then they are being paid to little. Again this is bad but not primarily because the workers are getting too little pay. All workers, public and private would prefer to be paid more.

It’s a problem because there are workers somewhere out in the private sector who could be creating more value as a public sector worker. This may strike some more libertarian readers as crazy. Yet, consider the following simplistic example.

A talented driver might face a choice of whether to to drive a fire engine or drive a tractor trailer. Both involve a special set of skills that is rewarded by higher pay. It could be the case that human welfare is higher if the best drivers all drove private tractor trailers, but this is not obviously the case. There is a lot on the line in getting a fire engine to a fire quickly and safely. Having the worst or even a mediocre set of drivers could easily be more costly to the public than offering higher pay.

Now, we might imagine that this simplistic analysis is mucked up by the presence of labor unions and public pay scales. Some of this is possible if the union prevents the firing of certain workers or doesn’t allow differences in pay based on differences in ability.

Simply driving up the salaries and benefits for public sector workers, however, will not cause basic labor market mechanics to collapse. This generates inefficiencies but the basic forces of supply and demand still assert themselves. We still have an upward slopping labor supply curve and unless the union is actively keeping people out, that doesn’t change at all.

Unlike in a private firm there is no profit maximizing relationship that matches labor demand to the marginal benefit of customers. This implies that there is no force to mitigate inefficiencies on the customer side. It doesn’t change the nature of the inefficiencies emanating from the labor market, though. Either the workers will have pay in excess of the marginal benefit of quality or the marginal benefit of quality will be in excess of pay.

In a private market the very same inefficiencies would occur. Constriction on the supply of workers would drive up the wage which would drive up prices for customers. The customers would respond by buying less and that would mitigate the inefficiency to some extent. Yet the failure in the labor market would be the same, the bar for quality is set too high.

We shouldn’t think that simply because public workers are employed by the government that the basic rules of supply and demand fall apart. Labor supply curves still slope upward and the quality of workers will still be a function of their compensation.

Ezra Klein asks

Have you or anyone close to you belonged to a union? How did that change your impressions of organized labor in general?

For 17 years or so my mother was a shop steward for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. She was a weaver in at Cone Mill’s White Oak plant in Greensboro, North Carolina. She eventually left that job to become a full time union organizer.

I grew up in the Union, so my impressions were formed by it. Those impressions evolved considerably as I grew older, both because of observations about the union and the world around it.

Observations from Growing Up in a Union

As a small child I thought that unions were the only way that workers could receive anything above subsistence wages. I also thought that there were intentional erected barriers in society that prevented people, particularly black people, from changing their class. If you were born working class then by-and-large you were destined to stay working class.

We did not use the phrase middle class. Carpenters, mechanics and other skilled laborers were considered well-to-do members of the working class. Doctors and lawyers and other professionals were considered part of the rich. The least intellectual would often refer to the rich generally as “white people.”

Though everyone was aware that working class white people were also white, this fact was not pointed out unless there was some explicitly racial conflict. The phrase “white people” generally referred to those not in the working class.

Though the issue rarely came up the assumption was that all rich people would be on the side of the Company. This wasn’t because of ideology but simply identity. The Company was rich. They were rich. There was no reason to presume people would betray their side.

None of this was taught. It was simply the air that we breathed. Working people were working people. The rich were the rich. Unions were the primary mechanism through which working people were protected from the rich.

A variant of Marxism was the accepted ideology of the Union, though the term Marxism was not regularly used. This Union Marxism was seen as different than communism in general or Soviet communism in particular. Those were viewed as perversions; a corrupted version of the perfect world. This corruption was attributed to moral weakness of their leaders.

There were some overt communist sympathizers in the Union, my parents among them. However, these people were considered radicals.

It was also not widely known that there was some worldview other than Union Marxism. Union Marxism had a role for the rich to play and they seemed to be playing it. Thus, it would not occur to someone that the rich had a different system of belief. They simply had a different role. Theirs was to oppress – ours was to struggle for freedom.

Again the Union was the primary instrument through which this could be accomplished. This was because the rich needed our work to maintain their lifestyle. If we withheld our work as a collective then they could be forced into some concessions. Though, this term was never used, the inability of the Union to demand and receive full compensation was thought to be limited by the free rider problem.

Collective action required that we all stand together but some people would naturally decline to suffer the pain of this and this would weaken the effort. This is why the Union had to constantly endeavor to increase its number and instill in its members a esprit de corps.

Loss of Faith

I began to loose my religion somewhere around the age of 10 or 11. That may seem young and people may wonder what religion I had to lose. However, the Union was as pervasive as normal religion or ethnicity. At least by five years of age it had heavily influenced my worldview because it told me things about who I was in the world, who my family was, and who other families were.

Yet by around 10 those things seemed not to be so true. For one thing I in math and science I was tracked along with the children of rich kids. I had rich kid friends and went to visit their homes. I would mention sometimes in the company of their parents that they were rich. This hardly failed to amuse them and they would say that they were not rich. They would explain that some other group of people was rich.

Though I didn’t believe them this planted the seeds of doubt because it meant that they did not share our worldview. That our worldview was true, that everyone knew it and that everyone played their part was something unsaid but core. Hearing people question it was shocking.

I also around this time became fascinated with the notion of community college. I don’t know how I first found this out but I realized that one could not be denied admittance to community college. At the same time, however, it promised access to jobs that were better paying than most working class jobs.

This was sharply at odds with the core theory. The core theory suggested that the system was designed to keep the majority of us from leaving the working class. There would be some exceptions and my parents expected me to be one. Yet, the majority was presumed to be held down.

Yet, here was a vehicle for rising somewhat and it said that admissions were open. Why then I wondered could we not all go to this community college and all escape. I was told that there would not be enough of these skilled jobs for all of us. This seemed unsatisfying and no reason not to try.

The final crack came when my mother became a union organizer. She was regularly admonished for spending too much time helping workers solve nonwork related problems and not enough time building membership.

I became convinced that dues rather than solidarity was behind the drive for more members. My faith in unionism was crushed and I went looking for other answers.

I’m not sure how I was introduced to it but within a short time I had discovered John Locke and become obsessed with Thomas Jefferson. It was soon after that, that I discovered Milton Friedman and then mainstream economics. All of these influences further weakened my belief that unions had even played a major role in the rise of living standards.

There has been a lot of complaining about how Wisconsin’s Governor Walker is using a short-term crisis to justify achieving a long-term goal in his battles with unions. Here is how Ezra describes it:

That’s how you keep a crisis from going to waste: You take a complicated problem that requires the apparent need for bold action and use it to achieve a longtime ideological objective. In this case, permanently weakening public-employee unions, a group much-loathed by Republicans in general and by the Republican legislators who have to battle them in elections in particular.

Taking a crisis and using it to serve a “longtime ideological objective” is a pretty good description of a lot of what went into the ARRA, including a lot of the infrastructure investments and Race to the Top. You might argue that “well those are just good policy!” and with some of it I might agree, but they are long-term goals and not the best use of short-term stimulus, and they certainly had ideological detractors on both the left and the right. These parts of the ARRA strike me as fairly comparable to what Governor Walker is doing, so I’m not sure why anyone who didn’t complain about that aspect of the ARRA is complaining about this if they object to this type of policymaking per se. My guess is that most people are fine with this when the long-term ideological goals being met are their own.

Another complaint is that the unions are willing to make many of the concessions that the Governor is asking for that will directly affect the budget, so going after collective bargaining rights is unnecessary. But liberals should understand very well that short-term concessions aren’t a long-term fix if structural issues ensure that in the long-run those concessions can and likely will be undone.

I want to quote Ezra at length here writing about the financial sector, because it’s the kind of long-term political and institutional analysis that liberals are ignoring in this debate when they point to the concessions unions are offering as sufficient:

….I don’t believe you can effectively regulate the financial industry so long as it’s sucking up about a third of domestic profits. The incentives to take massive risks will just be too great. The power to bribe Washington to dismantle regulations and legislation will be irresistible over time.

The situation is worsened because the financial sector doesn’t face the countervailing political pressures that other industries face… Once the memory of this crisis fades a bit, they’re basically alone in the issue space… Few legislators have strong, preexisting interest and understanding of the issue. There’s no real advocacy community. Maybe there’ll be somewhat more of all this after this crisis finishes. But I doubt there’ll be that much. And that makes me very skeptical that regulatory solutions will survive for very long. There’s money, expertise and interest on one side of the ledger, and the other side is likely to be spending its time on other things. How long till one party or the other needs to fund a tough reelection campaign and cuts a quiet deal with the financial sector? Particularly in a post-Citizens United election environment? It’s probably more than five years, but is it more than 15?

The point is that you can put the public sector on a sound financial setting today with the concessions from the unions, but that doesn’t address the power they have to claw back any concessions once they find themselves with in a situation where “one party or the other needs to fund a tough reelection campaign and cuts a quiet deal” with them. Now any attempt to curtail long-term institutionalized power must look at costs and benefits, but it’s important to have that discussion and not simply pretend that short-term concessions will stick. Importantly, if we mostly agree to the desirability of the immediate concessions, then the long-term sustainability of them becomes the issue.

A problem I have tried to highlight is that healthism (medical care, “healthy lifestyles”, prevention, etc) does not always lead to better average outcomes.

A study I just ran across offered people a choice between enhanced probability of survival, a pretty major health outcome, and raw healthism. The people chose healthism.

Cure me even if it kills me: preferences for invasive cancer treatment.

PURPOSE: When making medical decisions, people often care not only about what happens but also about whether the outcome was a result of actions voluntarily taken or a result of inaction. This study assessed the proportion of people choosing nonoptimal treatments (treatments which reduced survival chances) when presented with hypothetical cancer scenarios which varied by outcome cause.

METHODS: A randomized survey experiment tested preferences for curing an existent cancer with 2 possible treatments (medication or surgery) and 2 effects of treatment (beneficial or harmful). Participants were 112 prospective jurors in the Philadelphia County Courthouse and 218 visitors to the Detroit-Wayne County Metropolitan Airport.

RESULTS: When treatment was beneficial, 27% of participants rejected medication, whereas only 10% rejected surgery with identical outcomes ( 2 = 5.87, P < 0.02). When treatment was harmful, participants offered surgery were significantly more inclined to take action (65% v. 38%, chi(2) = 11.40, P = 0.001), even though doing so reduced overall survival chances.

CONCLUSIONS: Faced with hypothetical cancer diagnoses, many people say they would pursue treatment even if doing so would increase their chance of death. This tendency toward active treatment is notably stronger when the treatment offered is surgery instead of medication. Our study suggests that few people can imagine standing by and doing nothing after being diagnosed with cancer, and it should serve to remind clinicians that, for many patients, the best treatment alternative may not only depend on the medical outcomes they can expect to experience but also on whether those outcomes are achieved actively or passively.

Now, there are lots of reasons why this might make sense. People want to go down swinging. They want to feel like they did something.

It may be that on a deep level we are not programmed to avoid death so much as we are programmed to fight for life. This makes perfect sense as an evolutionary design. Attack-threats-to-life is an easier problem to solve than maximize-life-expectancy and in the natural environment the two are likely to yield roughly the same answer.

However, in the modern environment this is not always the case. Sometimes taking a wait-and-see approach is the optimal survival strategy, even if it doesn’t feel right.

The policy question within all of this is whether or not the government should subsidize, fully in some cases, people making choices which are likely to lead to worse health outcomes. I am of course not suggesting that people, not be allowed to pursue worse health outcomes if that’s what they want.

However, should the state be picking up the tab?

Robin Hanson critiques Chrystia Freeland’s take on our billionaire overlords.

It doesn’t seem to matter to Freeland how deservingly the rich obtain or spend their wealth; they still must be taxed to help average Americans, even if that slows the lifting of Chinese and Indians out of poverty. It isn’t clear why she recommends the rich eagerly submit to such taxation; she suggests taxation will happen whether they like it or not. Why fear “populism” beyond its taxation? The point seems more to scold the rich, in order to reassure the rest of us that we are justified in taxing them.

It may be the case that many calling for higher taxes on the rich are belittling or even demonizing their contributions as a way to justify higher taxes.

I am starting to believe that the belittling and demonization are at least as important to many of the new rich as the taxation itself.

That sets up the possibility for a trade. We praise the rich as we redistribute their money. I am not completely joking when I suggest there might be room to turn taxation from a welfare destroying necessity to a welfare enhancing activity for everyone involved.

Suppose we start a government website which shows the taxes paid by the wealthiest Americans but instead of listing them in terms of dollars we list them in terms of “kids treated under CHIP” or “soldiers sponsored” or some other meaningful measure of government spending.

Right now paying taxes is a sign of low status. You allowed the government to get your money. However, if we advertise broadly what the money pays for then we can push tax paying as a high status activity.

This is crucial because most of the spending among the wealthy whether it is for a giant yachts or malaria vaccines is ultimately a status competition. Its either who has the biggest toys or who has done the most to save the world.

This is not a dig at the rich. Human are programmed to focus almost exclusively on status competition whenever material survival becomes a non-issue. This is why both high schools and senior homes are full of cliques.

What we want is not destroy status competition, that would be impossible even if it was desirable. What we want is to channel it.

Some status competition is obviously destructive. Tax evasion as a status competition – see Leona Helmsley– is destructive. However, if tax paying is promoted as a status competition it becomes productive. It serves the same function for the people in the competition but it serves an improved function for society.

Now, a key question Robin would be sure to ask is, why should we think paying taxes is productive. What about giving money to the poor in India. Isn’t that better than paying taxes.

There is a longer moral case to be hashed out. However, my short answer is that maintaining a pro-market polity is productive and this is becomes less likely when the average person sees the market as primarily benefiting others.

Arnold Kling offers this quiz

Which of the following impediments to economic adjustment do you believe to be the most important?

a) the cost of establishing a new enterprise

b) the cost of integrating new workers and equipment into an existing enterprise

c) the cost of adapting physical and human capital to new circumstances

d) the cost of whiting out an old price list (menu) and updating it with new pricesIf you answered (d), then congratulations–you have shown your New Keynesian bona fides. If you answered anything else, then congratulations–you have shown common sense.

Indeed, I did answer (d) and so I suppose its incumbent upon me to convince readers that I have some sense, even if its not common.

The key part of the question is “impediments to economic adjustment” which is moving from one state of economic affairs to another. To practice with Arnold’s paradigm, to establishing new economy wide patterns of trade.

There are a few issues here.

One, the first three costs are very large to individual businesses attempting to establish new trade patterns. So, from a business owners perspective its natural to see them as a big deal.

However, in the background of the economy new patterns are being created and destroyed all constantly. As noted before this happens in the best economy and in the worst.

So, when we think about the economy wide pattern disruption the question isn’t so much what makes it difficult to start new sustainable patterns or end unsustainable ones. The question is, what would create even a moderate degree of covariance in the creation or destruction of patterns.

Because the churn of the economy is so tumultuous it only takes a slight shift in the tendency of patterns to open up or the tendency of patterns to close in order for us to experience what we would call a painful recession.

A related phenomenon for the broader audience is this. At the beginning of the recession I was warning friends and family as well as officials to batten down the hatches.

An in-law of mine was puzzled. How, she asked, can a huge recession be heading our way when she goes to the malls everyday and there are still plenty of people there. It seemed people were still buying things to her.

I answered, that for her particular mall – which was in a rapidly growing section of a rapidly growing city – to suddenly empty out, would not indicate a simple recession but the likely end of Western Civilization. I genuinely meant that. An event powerful enough to collapse all major patterns of trade in that area, in that short of a time period, would be a potentially civilization ending event.

The issue is not, of course, that the mall is keystone of humanity. It is that abandoning existing patterns of trade is costly. In order to suddenly convince everyone at the same time to do it, something really bad must happen.

To bring us full circle, the thing about changing the price lists is not that it’s a big deal for any pattern. Its that its highly correlated between patterns. For there to be no disruption each pattern must change in co-ordination with all other patterns.

That’s the first thing that makes price changes important for patterns of trade.

The second is that price is the language in which patterns communicate to one another. Lets think of a single pattern as similar to a neuron in a giant brain that is our economy. Prices are like the signals the neurons send to one another.

Because of the, on the scale of things small, cost of changing prices one of our neurons is slow in relaying its signals forward. This will affect the communication with the neighboring neurons which our neuron experiences as bad business.

However, more importantly for the entire economy, it will disrupt every signal traveling through that neuron. Some of those signals are incredibly distant to the neuron in question and have no direct business relationship. Yet, the entire network will suffer.

Now, lets suppose that all at once 30% or 40% of the neurons become slow in transmitting signals. The entire communication process of the net becomes impaired. Not destroyed. Signals get through eventually and communication does happen. However, there is noticeable widespread impairment.

This is how I would think of a recession.

There is a churn happening in the patterns of trade. Small highly correlated adjustments to that pattern cause widespread impairment. This impairment leads to a slightly faster destruction of patterns and slightly slower creation. The net result is that the number of people left without a pattern rises and we experience cyclical unemployment.

I understand this type of argument is frequently tendentious and rarely persuasive, but I think it is truly apt in this case: if one of the casualties of the drug war was that things like this were happening in middle class American towns there would be no drug war

Just after Christmas, drug hitmen rolled into the isolated village of Tierras Coloradas and burnt it down, leaving more than 150 people, mostly children, homeless in the raw mountain winter….

On December 28, two days after the initial raid, a column of 50 to 60 men, some in military-type uniforms and ski masks, filed on foot down a steep mountain road and torched three dozen homes — about half the village — as well as two schools, 17 trucks, the radio receiver and the community store.

The attack on Tierras Coloradas is one of the most dramatic examples yet of a still largely hidden phenomenon of Mexico’s drugs war: people forced from their homes by the violence.

It’s hard to grow up in any class in America without knowing someone with some kind of drug problem. So when voters in this country think about the costs of decriminalization, I think they’re probably mostly considering the people they know who would have developed worse drug problems had they been more available. What they don’t think of are the Mexican villagers being harassed and murdered because our drug laws create profit centers for their criminals.

Who we are or aren’t thinking about is important, because the only way the utilitarian calculus of our drug laws comes down in favor our of current system is if you value the well-being of Mexicans as being worth an order of magnitude less than Americans. Even then you’d probably have to value the welfare of the Americans who are rotting in jail for non-violent drug crimes very low in order to tip the utilitarian scales in favor of current policy. Something is dreadfully wrong with our social welfare function if we can’t clearly and unambiguously declare that the costs of the status quo are vastly outweighing it’s benefits. I suspect the problem is the people whose welfare we aren’t fully considering.

Could Tyler Cowen be raising awareness of a failure of Information Revolution to trickle down to the common man, just as it begins to rain buckets.

For a long time a certain set of economists has griped about health care. One of my particular gripes has been the very concept of a physician in the modern era.

A physician is more or less a human database and an incredibly expensive one. With medical training we basically take some of the most valuable brains on earth and hack them into doing something a brain is not intended to do: store and retrieve massive amounts specific information on demand with very low error rates.

On the other hand we have this machine called a computer which does this effortlessly and at low cost. Bare minimum we should forget about cramming drug interactions into human minds and just let them look it up in a database.

But, why not take it a step further and just get rid of the human altogether? Literally tens of thousands of people die every year because doctors are, well, only human, and make diagnostic mistakes which can later be identified as violating evidence based medicine.

The problem I always saw was how to convince people that yes, a computer can beat House, MD. Well IBM can’t go head-to-head with House but maybe beating Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter might help.

Looks like that’s what they had in mind for Watson. From IBM

Beyond Jeopardy!, the technology behind Watson can be adapted to solve problems and drive progress in various fields. The computer has the ability to sift through vast amounts of data and return precise answers, ranking its confidence in its answers. The technology could be applied in areas such as healthcare, to help accurately diagnose patients, to improve online self-service help desks, to provide tourists and citizens with specific information regarding cities, prompt customer support via phone, and much more.

For now, I see via Dan Bowman, that IBM is saying very kind, political things like

“You’re never going to replace a trained doctor or nurse,” Dr. Joseph Jasinski, a member of IBM Research’s healthcare and life sciences team said in the video. “But certainly a system like Watson could be a physician’s assistant. It could help to check on things: ‘Did you consider this? Did you consider that?'”

This is how you always open. Oh don’t worry. You’re irreplaceable. We’re just here to help. I mean a robot can lift heavy things for you, but you’ll always need a trained autoworker.

Paul Krugman makes the case for a higher inflation target

But what really stands out, if you assume that discretionary fiscal policy won’t be there when you need it, is that this makes the case for a higher inflation target. Olivier Blanchard, at the IMF, made just that case a year ago(pdf). If we’d come into this crisis with 4 or 5 percent inflation, not 2, there would have been more scope for conventional monetary policy to act before hitting the zero lower bound.

Paul Krugman makes the case for a higher inflation target. This sounds a lot like the argument I have been making for a while, and it should. Paul and I largely agree on how the economy works.

We disagree on whether government spending can be targeted in effective fine grained ways, but that’s the point. Disagreement over the effectiveness of market versus public allocation of resources should not alter your view on the relationship between monetary policy and recessions.

I have been meaning to do a post of the “huge surge” in money the Fed has printed and its implications for the future.

Jim Hamilton has a nice wonky discussion of it, though I am a bit confused by his point about there being no safe interest bearing overnight loans. This is a function of monetary policy not a constraint.

Anyway, I thought I would discuss the issue in a bit more pedestrian way:

Early on I thought the concern over the huge spike in bank reserves was limited to Peter Schiff and his crew. While they are passionate they aren’t really that big a part of the conversation.

However,I have heard more and more economists and policy folks worry out loud about the tons of cash on bank balance sheets and whether it could spark hyperinflation.

I believe those folks are unaware that the conduct of monetary policy changed in October 2008. The Fed moved away from a straight forward “minimum reserve system” to a new a “floor system”

The old system depended critically on the minimum reserve requirement. By law, banks have to have a minimum of 10% cash in reserve. That is, take the value of all checking accounts the bank has open. Take 10% of that number. That’s how much cash you have to hold in the vault or on account with the federal reserve.

Banks didn’t want to hold extra cash in the vault because it paid no interest. Getting paid interest is how they make their living. So, you could pretty much bet that banks were going to try to have exactly 10% in reserves, no more, no less.

Indeed, to facilitate this, banks would loan each other money overnight to make sure that they always hit the target exactly. This overnight market is the Fed Funds market.

When the Fed shrank the supply of money it became harder for all banks to hit the target simultaneously and the interest rate charged in the Fed Funds market rose. Its important to note that this rise occurs naturally through the buying and selling agreements of banks. The Fed does not dictate the Fed Funds rate.

However, banks are usually very predictable. And, so the Fed is able to target a Federal Funds rate. That is, the Fed would increase or decrease the supply of money until the Fed Funds rate landed where the Fed wanted it to.

During the Summer of 07 the Fed Funds market began to act erratically. Things went really wild one day in August, I don’t remember the exact date off hand.

I was preparing a talk on Medicaid one morning, when my phone starting buzzing with alert after alert. The Fed Funds market had spiked the previous night and some institutions were scrambling for for Funds. There was widespread chatter about what was going to happen the next night. Were major banks going to miss their targets?

This is the moment I mark as the official beginning of the Global Financial Crisis.

In the following year the Fed took bunch of steps to try to alleviate the crisis. Each step would tamp down the panic for a while but it would flare up again.

In October of 2008 the Fed began paying interest on reserves. What this did was set a floor in the Fed Funds market. That is, the Fed said it was always willing to pay you a certain interest rate on any reserves you had and so why even bother loaning to banks for less?

Why would they want to do this when the Fed Funds and other important market rates were racing out of control?

They wanted to do it because they intended to flood the Fed Funds market with money. So much money that any spikes would be drowned out. However, they didn’t want banks to go out and loan out that money for fear that a rapid increase in loans would cause runaway inflation.

So they created a floor and then flooded the market. This essentially brought an end to the liquidity crisis in the daylight banking system. The daylight banking system still had a solvency crisis and that’s where TARP came in.

The shadow banking system was all jacked up beyond repair and there wasn’t a whole lot that anyone could do about it except to try to keep it from bringing down the rest of the financial system with it.

This move to end the liquidity crisis also severed the link between the amount of reserves in the system and the amount of money banks were loaning. Money is created not so much when it is printed but when it is loaned. As long as it sits in the vault gathering dust, its not going to drive up prices.

So this is why the amount of reserves has skyrocketed but there has not been a massive increase in lending.

Now yes, there are a lot of questions about the interest on reserves program and whether it cuts off an important channel of monetary policy. I don’t think so. Scott Sumner would disagree.

However, there is no particular reason to expect that “any day now” money will come flooding out of banks and create hyperinflation.

The system was redesigned to make banks keep a larger fraction of the money inside the vault.

So two misunderstandings. One is that you have to balance the budget to reduce the debt load. Yglesias tackles that here.

With great fear of being taken out of context by Ron Paul supporters I should make clear that the debt only has to grow more slowly than the Nominal GDP, not Real GDP for the debt burden to fall.

So if our total debt is $10 Trillion and our economy is growing at 5% nominally, then any deficit less that $500 Billion will tend to shrink the debt burden. Any deficit greater than $500 Billion will tend to increase it. This is why we haven’t had many surpluses in US history but the the debt burden is usually falling.

The reason its nominal GDP that counts is because interest payments are figured in as part of the deficit. Suppose we have lots of inflation. That will tend to make interest payments on the debt rise. You could think of this as the debt growing to match inflation.

However, the US Budget accounts for interest payments on the debt. So when you are comparing the deficit to the growth rate of the economy, you have already accounted for the debt growth due to inflation.

The second thing you can see from that graph is that the debt burden has been much higher in the past.

In 2009 we just broke through the Reagan-Bush peak and haven’t come close to the WWII peak. Moreover, this is dominated by the recession. The recession contributes in four ways

- A smaller economy means less revenue and hence a higher deficit. This amplified by our progressive tax structure

- A smaller economy means lower GDP, and so the debt burden is divided by a smaller number

- Tax cuts, spurred on by recession have brought down revenue still further

- Spending, automatic and planned has increased in response to the recession

As the economy improves the northward spike will abate.

In the out years we can talk about deficits that are set to accumulate. However, this represents health care costs that the government has promised to pay for but not promised to tax for. In theory either of those promises could be changed.

More importantly, however, health care takes resources away from the rest of the economy whether the government pays for it or not. Obsessing over future budget deficits because of Medicare and Medicaid but ignoring future stagnant or even falling take home pay because of private health care is silly.

We could just end any and all public financing for health care tomorrow and the budget deficit and future deficits would vanish. Woo-hoo! However, the problem of expensive health care would still be with us.

A commenter notes that my ideas on stimulus sound a lot like Greg Mankiw’s. This shouldn’t be odd as Greg and I have very similar view on how the economy works.

We have different views on underlying social morality, but that’s the point. From an intellectual perspective whether you think there should be more or less redistribution should have no bearing on whether you think stimulus is effective in closing the output gap and whether or not you think broad based tax cuts are the fastest and most effective way to get there.

One of the things I have noticed on the blogosphere, Facebook and other outlets where I have access to popular opinion is that skepticism goes out the window when it collides with cynicism.

In an only mild exaggeration, if I were to propose that the moon were made out of cheese, I would be met with a deep skepticism by almost everyone. However, if I were to propose to a unified subgroup, that their sociopolitical adversaries had conspired to make them believe the moon was not made out of cheese the skepticism level would drop dramatically.

Still most people would combat it, but far less forcefully and more on the grounds that “every knows that the moon is not made of cheese” rather than on genuine skepticism.

However, no matter how likely you think it is that some one is tricking you into believe the moon is not made cheese, that must be less likely than moon being actually made out of cheese. For someone to hide the truth from you, it must first be the truth.

Let me give a more concrete but unfortunately more charged example. There is a debate over whether or not the Obama Stimulus worked. As I have said before, I favored a different type of stimulus, both at the time and now. This gives me enough cachet to enter into non-heated conversations with strong Obama detractors.

They ask me frequently whether or not I “really believe” the stimulus worked. I say, “I presume so.” Then they counter with a line of reasoning more or less like the following:

The economy was bad even with the stimulus. It was worse in fact than the Obama administration said it would be without the stimulus. The Obama administration would like us to believe that it would have been even worse without their stimulus. However, this is just a convenient ruse. One cannot prove a counter-factual. Thus we cannot know whether the economy would have been worse without the stimulus. Thus we should not believe the Obama’s administration’s claim that stimulus worked.

This is all well and good except that its an argument that the Obama administration has no credibility on stimulus. That fact alone can’t lower your estimate of stimulus’s effectiveness from what it was before the crisis.

Why?

Well presumably the Obama administration, at absolute worst, will say whatever it needs to say to put the stimulus in the best light. If the stimulus worked, they will say it worked. If it did not work then they will still say it worked.

This implies that statements from the Obama administration are orthogonal to the truth. That is, utterly uninfluenced by it.

However, if a statement is orthogonal to the truth then it cannot rationally affect your estimate of the truth. That is, it simply doesn’t matter what the Obama administration says. Your best guess at the truth is whatever you thought the truth was before. You might as well simply ignore everything the Obama administration says.

Yet, this is not what the argument above is asking. It is asking that I lower my estimate that stimulus is effective based on the Obama administration’s lack of credibility. This is only rational if I think the Obama administration is anti-truth. That is, that they seek to lie even when it is not in their best interest to do so.

Or, said another way I have to believe if the stimulus had worked the Administration would lie to me and tell me that it didn’t. I have to believe they would do this because they enjoy lying or are otherwise motivated to spread disinformation for its own sake.

Said, in additional way, I have to believe not that the Obama administration has no credibility, but that they have negative credibility. If I take what they say and simply assume the opposite, I will be right more than not.

Its an easy proof but beyond this post that negative credibility is credibility. And, that someone who always lied no matter what, is just as trustworthy as someone who always tells the truth. You simply have to logically invert the questions.

So, back to the point, this implies that, at worst, the Obama administration has zero credibility. Negative credibility would be better than zero credibility.

However, zero credibility by definition means that you should believe whatever you believed before. It also by the way, means that the fact that the economy was worse than the Obama administration predicted means nothing. After all, they have zero credibility. Under that assumption, everything they say is meaningless.

The moral of that example is that there is no consistent amount of cynicism about the Obama Administration that should lead you to downgrade your estimate that stimulus worked.

Now, if you independent of the Administration, thought that unemployment would top out at 9% in the absence of stimulus, and you independently hold to that prediction then the fact that with stimulus unemployment rose above 9% is evidence that the stimulus failed. However, it’s a rare person that I meet, who is making this claim.

The moral of the whole post is that assuming your adversaries have low fidelity to the truth is not the same as assuming that they have high fidelity to lies. Generally speaking the worst I should think of someone is that, something is no more or less likely because they told me it was so. I should not lower my skepticism of their proposition being false, simply because they told me it was true.

I couldn’t find the paper I want to reference but I remember reading a convincing analysis a while back that the advantage to consumers from Fannie and Freddie loans was on the order of 7 basis points.

The story was more or less that the difference between loans just over the Fannie/Freddie cap and those just under was only about 20 bps. Of that the estimated that less than half was due to the fact that the implicit federal guarantee was driving down Fannie/Freddie loan rates but that over least half was due to the fact that Fannie and Freddie’s guarantee was driving up rates on other loans.

Basically, investors had a choice: they could either by the Fannie Freddie loans with the implicit guarantee or they could buy private label mortgages with no guarantee. Obviously investors prefer to be guaranteed and so money moved from private label to Fannie/Freddie. This dropped Fannie/Freddie rates somewhat but it caused private label to rise by even more.

The moral of the story is that unless you think 7 basis points, which is .07% makes housing much more affordable, then Fannie and Freddie are not really that effective at providing affordable housing.

My question, however, is: what are the macro-economic implications of having no mortgage buyer with a guarantee.

As you can see during the crisis the spread exploded

Indeed, that was a big signal that things were going horribly wrong.

The rise in the spread during 2009 can be somewhat attributed the Fed’s buying of Fannie and Freddie bonds directly. However there was a clear jump in 07 that was related to the beginning of the housing crash.

Also its no well kept secret that Fannie and Freddie became the lender of only resort during much of the crisis. Rising to 100% by mid 2010

The question is: what would have happened to the US economy had Fannie and Freddie not been in a position to offset the collapse in the private mortgage market.

One possibility is that the price of housing would have collapsed. I know that people are still shell shocked by the decline in housing prices, but while there was a dramatic fall it was hardly a full scale collapse.

Here is the Case-Shiller 10-city index

We are still 60% above the year 2000 level, roughly where we were in 2003. Imagine a collapse all the way back to 1992 levels? This is certainly possible, it happened in Detroit.

Even bigger collapses are theoretically possible. If credit completely tightens then the market will turn to cash buyers and price will fall to the point where cash buyers can meet forced sellers.

The question is how bad would that have been macroeconomically?

On school of thought would be that reaching equilibrium faster would reduce uncertainty. It would cause a much larger wave of strategic defaults, but that on the other hand would have meant a huge decline in the debt overhand for consumers.

A key issue is whether or not the private banking sector could have been as easily saved without Fannie or Freddie. This I do not know. I would tend to think that the insolvency would have been much deeper and the success of TARP less certain.

In short, while I have little concern that the demise in Fannie or Freddie mean much for affordability I am more concerned about macroeconomic stability. Without a mortgage lender of last resort, much larger crashes in housing prices are possible and with that the possible unrescueable collapse of retail banking.

Krugman says that he doesn’t want to relitigate the debate over stimulus. I am less inclined to let bygones be bygones.

Now, in contrary I don’t think Obama should have started with a higher number for spending – though that would have been preferable to what happened.

I would have started with a much higher number for tax cuts. Indeed, “the stimulus” could have been exclusively tax cuts and much much bigger ones. As I floated before, there was the possibility of simply suspending the payroll tax entirely.

Other measures could have been take on practical rather than stimulus grounds. For example, extending aid either in the form of grants or loans to the states, not explicitly for “stimulus” but because otherwise teachers and police officers would have been laid off. An expansion of unemployment and COBRA benefits simply because they are needed by the newly unemployed.

However, the big bang, could have come from tax cuts. Indeed, as Krugman points out – what little boost there was did in fact come from the tax cut provisions. There was little expansion in government spending when federal increases are combined with state and local decreases.

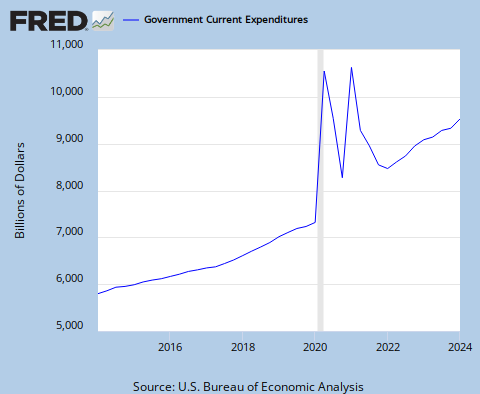

Indeed, on net the government spending seems to have been mildly contractionary. Here is growth in government spending relative to its longer run average of more or less 6 percent.

Bars above zero represent when government expenditures were growing faster than 6%, bars below zero when they were growing slower.

Looking at the the last few years, there is more mass below the line than above it, meaning that the growth in government spending has tended to be below the long run average. The belt was tightened in effect, though not as much as the economy overall, of course.

Since that was the net effect, why not propose it that way? Call “stimulus” the large payroll tax cuts. Propose aid to the states in an effort to offset otherwise massive budget cuts.

This was a major error for the Administration, not just in political terms, but much more importantly in policy terms. Failure to provide adequate stimulus may have permanently displaced some people from the labor market and has scarred the skill development of several cohorts of high school and college graduates.

So that San Francisco Fed says that the natural rate of unemployment may have risen to nearly 7%.

Mounting evidence suggests that structural factors may have increased the “normal” rate of unemployment to about 6.7%. Much of this increase is likely to be temporary. In particular, the extension of unemployment benefits probably accounts for about half of the increase. But, even with a 6.7% natural rate, current and forecasted levels of unemployment imply that significant labor market slack will persist for several years.

Its important to remember that monetary policy itself can influence the natural rate.

When we look at the history of Eurosclerosis, the tendency of many European countries to have stubbornly high unemployment despite growing economies, we see that those nations most aggressive in bringing down inflation had the worse cases of sclerosis. More importantly, countries which reversed tight money policies in the face of severe unemployment saw the natural rate of unemployment fall.

Laurence Ball does a nice review.

Another way of saying all of this: Recession are caused by money, either a change in the demand for it or the supply of it. This is not to say fiscal policy plays no role but simply that unemployment rises sharply when people cannot build a cushion of savings as fast as they would like to. Broad based tax cuts for example, could allow people to build up their savings faster than they would otherwise.

However, once going, unemployment can beget unemployment as people who haven’t had a job in a while are less employable. One of the things we notice even from recessions of old is that unemployment rises faster than it falls.

This suggests that getting a job is not simply the inverse of losing one. The labor force is changed by mass layoffs. That change has to be undone.

What does all of that mean?

It means that we shouldn’t be inclined to “settle” for an unemployment rate of 7% or see that as the new target. Sustained aggressive monetary policy will bring the natural rate down over time. We should be aiming to “shoot past” 7%, knowing that the new target will be lower than 7% by the time we get there.

As a side note, I am unsure how to approach the hard money folks, who at the moment I see as the greatest immediate impediment to the health of the nation. On the one hand we can make the very true case that inflation is nothing to be worried about now. The Fed can continue to press forward without fear of rising much above its presumed target of a 2% core rate, anytime soon.

My fear is that this doesn’t address the long run issue, that we may need to go above that comfort zone to undo some of the damage of this recession. That kind of talk gets a lot of people nervous and may even hurt efforts at current monetary expansion.

Yet, resorting to the “but inflation is low now” position almost concedes that any inflation rate higher than 2% is indeed undesirable. That is not what I mean at all.

Scott Sumner has a post on, among other things, the six most important public policy issues. I completely agree with Sumner on this list, and look at as a guide to winning the future. His six issues are:

1. The huge rise in occupational licensing.

2. The huge rise in people incarcerated in the war on drugs, and also the scandalous reluctance of doctors to prescribe adequate pain medication (also due to the war on drugs.)

3. The need for more legal immigration.

4. The need to replace taxes on capital with progressive consumption taxes.

5. Local zoning rules that prevent dense development.

6. Tax exemptions for mortgage interest and health insurance.

In terms of importance for our future, the list is sort of lacking in intellectual property, copyright, technology, and education, but I don’t know that those problems lend themselves to bullet points quite so easily. The only real disagreement I have with Sumner is his explanation for why these policies don’t get reported on, which is that there isn’t enough disagreement along ideological lines:

Most idealistic intellectuals agree with me on all of these issues. They are not issues that divide the left and the right. It’s also true that most real world politicians agree on these issues. However their views are exactly the opposite of the views of intellectuals. Hence there is no “policy debate” in either the political or intellectual arenas, and hence no “fight” for the media to report. They become invisible issues.

The missing piece of this puzzle is that the intellectual agreement on these issues isn’t just the opposite of real world politician’s, but the opposite of the rest of the real world. At the average dinner table in this country, anyone advocating what Sumner might call the intellectual consensus on any of these issues would face a lot of disagreement, and would frequently be greeted by surprise that a reasonable person would ever dream of advocating for, say, for more immigration or less occupational licensing. The problem is that you can pretty much go right down this list and point out the biases from The Myth of the Rational Voter that will tilt public opinion towards bad policies. The median voter is as important of an obstacle on these issue as interest group influence on politicians, and unfortunately the median voter’s belief’s are a much more intractable problem.

Brad Delong got me interested in the details of a few of these cases

You can sleep easy if you play by the rules even if you think the rules are non-optimal, as long as you point that out. That’s Milton Friedman.

You cannot sleep easy if you play by the rules if you think the rules give you a license to steal. That’s Robert Nozick, Robert Bork, and Ayn Rand.

That’s the difference between utilitarian and deontological theories. Deontology is a bitch.

To catch up, Robert Nozick freely entered into a lease with his landlord, Eric Segal. After living in apartment for a year or so, Nozick then sued Segal for violating rent control laws and further refused to move out unless paid additional compensation. According to his moral theories this constituted extortion.

Ayn Rand, received Social Security and possible Medicare payments to cover lung cancer treatment. This is despite her characterization of the welfare state as theft and a particularly egregious form of theft because it is legal.

Robert Bork sued the Yale Club after suffer a slip and fall, despite arguing against frivolous lawsuits. I couldn’t find enough information on Bork – in the short time I looked – to get a real sense of his moral philosophy concerning slip and falls.

For Nozick and Rand, however, these are clear breaches of the most common interpretations of their moral philosophy. Does this undermine their philosophy at all?

On one level we are of course tempted to say, no what is true is true regardless of whether the popularizer of those truths honors them. On the other hand “ought” implies “can.” If not even Nozick and Rand can hold to these principles are they a meaningful guide to how we ought to structure our society? While these are by no means view-killing breaches, they do raise the question: is anyone capable of living according to these maxims?

I looked a little in Nozick and Rand’s response. By my reading Nozick’s offers a fair degree of absolution for his philosophy while Rand’s leaves me scratching my head.

Nozick via Julian Sanchez

I knew at the time that when I let my intense irritation with representatives of Erich Segal lead me to invoke against him rent control laws that I opposed and disapproved of, that I would later come to regret it, but sometimes you have to do what you have to do.

This reads to me as this: Yes, what I did was wrong. I knew it at the time, but I was pissed.

This statement moves the onus from the philosophy to the individual. Had Nozick dithered and said “Well, but Segal deserved it” that would be different. Instead, he seems to admit that he acted immorally.

Said another way, its one thing to abandon your principles you when find that they are inconvenient to you. It’s another to fall victim to weakness of will and do something you know you will later regret. We don’t have any philosophy, save perhaps hedonism, that protects people from weakness of will.

Rand on the other hand claimed

It is obvious, in such cases, that a man receives his own money which was taken from him by force, directly and specifically, without his consent, against his own choice. Those who advocated such laws are morally guilty, since they assumed the “right” to force employers and unwilling co-workers. But the victims, who opposed such laws, have a clear right to any refund of their own money—and they would not advance the cause of freedom if they left their money, unclaimed, for the benefit of the welfare-state administration.

This is much iffier. Here she does seem to be saying that different rules apply to her followers simply because they are her followers. This has the feel of ad hocery. There might be significantly more, but it seems to be a more eloquent way of saying “We were just sticking it to the man, that was sticking it to us.”

Doesn’t the taking of benefits imply that more resources will have to be confiscated to support the program? And, while appealing for a refund makes perfect sense, simply using the system without a guarantee that you are matching funds put-in with funds taken-out and certainly without the express permission of the people who are currently being taxed seems morally ambiguous in Rand’s own terms.

A few people have pointed out this Pew poll that shows an inconsistent public. The public, for example, thinks the states should balance their budgets, just not by raising taxes or cutting spending.

Now, some people really might want the states to balance their budgets by magic. However, you don’t need that to get the results Pew finds.

Suppose that you have three people. Adam, who believes in cutting spending to balance the budget. Bill who believes in raising taxes to balance the budget and Chris who believes that state balanced budgets are a pro-cyclical economic destabilizer that should be alleviated by federal transfers, or as he likes to say, “lame.”

Now we are going to ask a few questions.

First we ask: Should the state stick to its balance budget requirement? Adam and Bill say yes. Chris says no. We confidently conclude that the public wants balanced budgets.

Second we ask: Should we cut spending? Adam says yes. Bill and Chris say no. We confidently conclude that the public doesn’t want to cut spending.

Third, we ask: Should we raise taxes? Adam and Chris say no. Bill says yes. We confidently conclude that the public doesn’t want to raise taxes.

But wait a minute! Is the public insane! How can we balance the budget if we don’t cut spending or raise taxes.

No the public as individuals are completely sane, but when aggregated into a whole they become irrational. And, importantly there is no clear way to make them rational, since each person is answering truthfully and with complete knowledge of the facts.

[We are going to leave out intensity scoring for now because its complicated and I don’t think it actually gets you what its proponents think it gets you]

This is one of the reasons why “the individual” is special level of organization. Trying to go below the individual, for example asking what kind of policy your parietal lobe wants, usually yields no meaningful answer. Going above the individual exposes you to this fundamental aggregation problem.

How the brain goes about solving this aggregation problem is still a mystery to us. If it feels like there are dozen distinct urges and desires pulling you in different directions, its because there are. Somehow, however, the brain integrates them into a surprisingly rational whole. As a society we don’t know how to do that.

One practical solution to this problem, employed by the founders of most modern democracies, was to create some form of deliberative legislature where people could hash out deals.

Sometimes these deals would include side payments. For example, Adam and Bill agree to build a bike ramp for Chris if he’ll vote for modest tax increases and modest spending cuts.

Today that type of deal making is under attack. Politicians are lambasted for voting against their party’s preferences. Side deals or pork are criticized as corrupt and immoral.

This is unfortunate because if Pew snapshot is correct, then a legislature that is purely faithful to its voters is a legislature inescapably bound by aggregate irrationality.

Don’t do it, Ezra. You just calmly finish drinking that diet soda and don’t concern yourself for one second. I know you’re worried, because you fearfully tweeted earlier today about this Tom Philpott story at Grist about how diet soda causes cancer. But the best thing you can do for your health is not listen to Tom Philpott, because the unnecessary stress caused by worrying about the aspartame in your diet soda is far more dangerous for you than the aspartame in your soda. Philpott brings two pieces of evidence to bear in his argument that diet soda is bad, neither of them will be unfamiliar to you if you’ve followed the debate (I use the term “debate” loosely, in the same sense that we’re “debating” whether 9/11 was an inside job). The first is the old story hippies tell each other around the campfire about how Donald Rumsfeld and Reagan-fueled ’80s snuck aspartame past the FDA with all sort of hijinks. Not only is this story old, so too is it’s debunking. The GAO was asked in 1987 to do a full retrospective study of the approval of aspartame by the FDA and here is what they reported:

FDA adequately followed its food additive approval process in approving aspartame for marketing by reviewing all of Searle’s aspartame studies, holding a public board of inquiry to discuss safety issues surrounding aspartame’s approval, and forming a panel to advise the Commissioner on those issues. Furthermore, when questions were raised about the Searle studies, FDA had an outside group of pathologists review crucial aspartame studies.

The second piece of evidence is a study by the Ramazzini Foundation, whose name also familiar to anyone following the aspartame “debate”. Here is what the FDA had to say about this study in September of 2010:

FDA could not conduct a complete and definitive review of the study because ERF did not provide the full study data. Based on the available data, however, we have identified significant shortcomings in the design, conduct, reporting, and interpretation of this study. FDA finds that the reliability and interpretation of the study outcome is compromised by these shortcomings and uncontrolled variables, such as the presence of infection in the test animals.

Additionally, the data that were provided to FDA do not appear to support the aspartame-related findings reported by ERF. Based on our review, pathological changes were incidental and appeared spontaneously in the study animals, and none of the histopathological changes reported appear to be related to treatment with aspartame.

The FDA aren’t alone in believing aspartame doesn’t cause cancer. They’re joined in this conclusion by The American Cancer Society, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the Mayo Clinic. So you can trust Tom Philpott and the Ramazzini Foundation or you can trust the most highly esteemed medical institutions in the United States. Like I said Ezra, drink up.

If you want even more details about this tall tale (let’s face it, you don’t), here is an older post where I dig in much more.

Will Wilkinson notes the intuition behind the golden warriors.

"Our currency should provide a reliable store of value—it should be guided by the rule of law, not the rule of men," Mr Ryan informed Mr Bernanke. "There is nothing more insidious that a country can do to its citizens than debase its currency". And who would disagree?

I would disagree.

First, that money is a reliable store of value is not a virtue but a regrettable defect of our economic system. It is extremely difficult to create money that is a workable medium-of-exchange without it having some value-storing properties. This is a fundamental problem that industrious minds work to solve whenever faced with it.

The less fundamental value money has the better. An item that is used as a medium-of-exchange cannot be put to productive use otherwise.

More to Ryan’s point, attempts to store value as money have the potential to collapse our entire economic system.

Money does not create anything. Value stored as money is value lost; lost because it represents resources not directed towards capital. Capital, unlike money, does create things. That people sometimes see it as advantageous to stop investing in capital and start holding money is the source of enormous economic instability.